Guilford County, the third most populous in North Carolina, is currently facing something of an electoral crisis. Earlier this month, data provided by the U.S. Elections Project at the University of Florida found that Guilford ranked first in the nation for the number of absentee ballots being marked as Not Accepted by the county board, at 4.8 percent. Of those voters whose ballots remain in limbo, Black voters have been overrepresented among the pulled ballots: As of this writing, while white voters saw their mail-in ballots set aside at a rate of 2.8 percent, Black voters were being marked at 9.7 percent.

A number of factors have led us here—some of them active voter suppression efforts, some of them having to do with the pandemic and the increase in absentee ballot requests by first-time users, and some with a stagnant Democratic Party that for years has failed to proactively embrace mail-in voting and educate voters on the process. Laws like the Voter ID bill, first passed in 2013 by the General Assembly, as well as its 2010 redistricting plan, are, as a federal judge put it, “almost surgically precise” in their desire to disenfranchise Black voters. But as North Carolina has proved during this election cycle, it is that end effect, rather than the intent, that matters most.

The pandemic has fundamentally altered the voting process, forcing many voters to fill out their ballots at home for the first time in their lives. Rather than come together to make a complicated process more accessible and streamlined, conservative politicians—still hoping to see through their years-long project of disenfranchising nonwhite, non-Republican voters—have instead opted to spread concerns about imagined voter fraud and muck up the courts with lawsuits that stand in the way of a commonsense solution.

It’s petty and racist, but it’s also working. The county boards of elections, like the one in Guilford County, are following the orders of the State Board of Elections, which is following the orders of state and federal courts, which are responding to the lawsuits by conservative officials. These institutions do not necessarily share the same goals as Republican politicians, but their responses so far have ultimately worked to the conservatives’ advantage: Black voters in North Carolina are being disproportionately denied the right to vote in the 2020 general election.

From the outset of the pandemic, it was apparent that there was no chance that the 2020 general election would run normally. Due to the need for social distancing, vote-by-mail rates have skyrocketed among the voting population. As of this writing, more than 420,000 voters have had their absentee ballots approved in North Carolina—twice the number of mailed ballots that the state received throughout the entire 2016 election cycle.

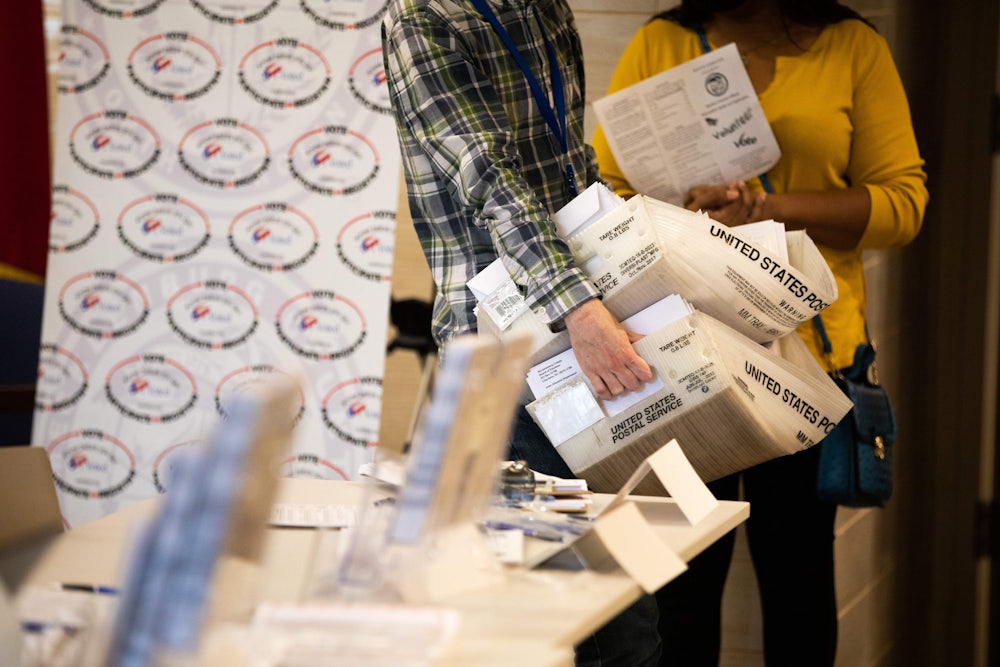

The sudden increase in mail-in voting—while a useful exercise in reminding people that there are more options available to them than voting in person on Election Day—has posed a logistical challenge for the county election boards tasked with sorting through and accepting these ballots. For example, earlier this week, an organization with the goal of increasing voter turnout mailed 11,000 North Carolinians the incorrect ballot application form. (The State Board of Elections then instructed everyone who received the forms to discard them, while the organization pledged to send those folks the correct applications.)

The uptick in mail-in voting and the accompanying hiccups have been joined by an unhealthy dose of fearmongering. On the presidential debate stage, President Trump called the ongoing balloting efforts, “a fraud and a shame.” In reaction to the North Carolina State Board of Elections making it easier for people to fix mistakes on their ballot, the president’s campaign recently sent letters to the 100 county election offices in the state, instructing them that “the NC Republican Party advises you to not follow the procedures.” Even back in April, Phil Berger, the Republican president pro tem of the state Senate, stoked the same baseless fears, warning readers of the Charlotte Observer that “though every eligible voter should have access to the ballot, no voter is rewarded by a system that is insecure and vulnerable to fraud.”

Responding to false claims of widespread voter fraud, Katelin Kaiser, the Voting Rights Legal Fellow for the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, told The New Republic, “We simply know that’s not true.” Kaiser, whose team works to ensure that North Carolina citizens have access to the ballot, noted that the concerted effort to cast doubt on mail-in voting remains a concern. But the most pressing issue facing both Guilford County and North Carolina is the fact that the state’s county election boards have been marking the mail-in ballots of Black voters as nonaccepted, or pending, at twice the rate of the rest of the population’s.

Part of this is due to inexperience with absentee voting. “Voting by mail, or voting by absentee ballot, is new to a lot of people—this is my first election voting by mail,” Kaiser said. The majority of these ballots are being pulled for having what is known as deficiencies. “Deficiencies can be something like the voter forgot to sign the ballot or forgot to sign the envelope,” Kaiser told me. In other words, a minor mistake. Speaking with Triad City Beat, Catawba College political science professor Michael Bitzer said that the disproportionate rate of discrepancies can be attributed to the fact that mail-in voting has long skewed toward white voters. “People whose first time it is to vote by mail may not fully understand the instructions,” Bitzer said. “In previous research, voting by mail is an overwhelmingly white method. Black voters are traditionally in-person voters.”

What the state board initially wanted to do, and what it instructed the county boards to do via four memos, was allow for these ballots to be “cured,” or fixed, by the voter. That meant contacting the voter and informing them of the deficiencies, or allowing the voter to fill out an affidavit confirming that the ballot is theirs. But a decision by the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina in early October, in reaction to the case N.C. Alliance v. State Board, instructed the state board to put a halt to all absentee ballot curing. The North Carolina state board then issued a memo that told the county boards to press pause on the easy-fix options, instructing them to “take no action” on ballots with errors until all lawsuits on the issue had been settled. It’s important to note that these ballots aren’t being thrown out or rejected by the county, Kaiser said—they’re just sitting around in secured locations, waiting for the courts to tell the state to tell the counties what they’re allowed to do. Like I said: a mess.

While the ability to vote has not been entirely stripped from these voters, in places like Guilford County, the rates are high enough to cause concern. The end result of complex processes of malicious disenfranchisement and bureaucratic ineptitude remains the same: Black voters having their ballots temporarily on hold with a potential rejection without due process.

But it is still important to understand that the lawsuits gumming up the works here are in fact the methods of those who are acting with purpose. The Republican Party, both nationally and in North Carolina, has for years tried to make voting less accessible for those outside its tent. A tried-and-true tactic to achieve this aim has been to make lots of loud noises about the threat of voter fraud (a particularly ironic sentiment given it was a North Carolina Republican Party operative who was charged in 2019 for running a ballot-collection scheme).

But this approach has also been accompanied by a string of policy decisions and, more recently, lawsuits to keep those policies in place. Along with the Voter ID requirement bill in 2013, the North Carolina General Assembly passed legislation that slashed early voting days and locations, axed same-day registration, and curbed the power of the college vote by outlawing out-of-precinct voting. It also drew districts following the 2010 census that specifically split towns and counties, particularly those with large Black populations, hoping to dilute their voting strength. The latest round of lawsuits to “prevent voter fraud” are in fact an extension of this same plan.

This extends far beyond Guilford County and North Carolina. The state is currently twisted in a knot of concurrent lawsuits pertaining to election procedures, a trend that has been mirrored by the rest of the country. Former Justice Department elections official Justin Levitt told the Associated Press that this election has triggered 260 lawsuits nationwide, with the AP calling this race, “the most litigated in American history.” And the back-and-forth nature of these rulings have made it difficult for voters to keep track of what the latest rules are. In South Carolina, for instance, the state courts determined that a witness signature was not necessary to validate a ballot, only to have that decision overturned, earlier this week, by the Supreme Court.

The task of ensuring one’s vote is actually counted in this election can be a difficult one to achieve—polling locations and hours have changed due to the pandemic, and absentee ballots and their distribution remain imperfect in terms of accessibility. And until the lawsuits against the election boards are settled, these issues are almost certain to persist through Election Day. For voters who will cast their ballot in the interim, Kaiser strongly suggested that people make a voting plan.

“It’s so important that you and your loved ones discuss it and figure out how you are going to vote in the 2020 general election,” Kaiser said. “This year is not like past years. Your typical polling place might not be the same as it was previously, because of the requirement of meeting social distance at the polls. And if you’re going to vote by mail, it’s really important that you know those deadlines.”

In North Carolina, the last day to register to vote is October 9, and the deadline to request an absentee ballot is 5 p.m. on October 27. Kaiser listed those dates with a warning: “Don’t wait until the last day.”