In earlier chapters of American history, bad presidents eventually led to good government. Andrew Johnson’s stupendous failures after the Civil War spurred Radical Republicans to take command of Reconstruction, briefly turning the American South into a multiracial democracy. Richard Nixon’s downfall in the Watergate scandal in 1974 inspired a decade’s worth of reform: the creation of inspectors general, new ethics and transparency standards for public officials, stronger anti-corruption laws for campaign finance violations and foreign bribery, and more.

Donald Trump’s presidency requires a similar reckoning. On Wednesday, Speaker Nancy Pelosi and other top House Democrats unveiled a new bill aimed at fixing some of the systemic weaknesses that Trump exposed in the American system of government over the past four years. “Our democracy is not self-effectuating—it takes work and a commitment to guard it against those who would undermine it, whether foreign or domestic,” six of the Democrats’ major committee chairs said in a statement. “It is time for Congress to strengthen the bedrock of our democracy and ensure our laws are strong enough to withstand a lawless president. That’s why we are acting today to introduce the Protecting Our Democracy Act.”

The bill is a tacit admission by Democratic leaders that existing laws have fallen short of their aspirations when constraining a president who is indifferent to the rule of law. Many of the post-Watergate reforms, for example, rely upon the president’s good faith to properly function. Other provisions, such as the purported ban on nepotism in federal hiring and the Hatch Act’s limits on using public resources for political gain, proved ineffectual without an independent enforcement mechanism. Some of Trump’s actions have gone beyond what past generations of lawmakers ever thought possible from a sitting president.

Perhaps the most significant provisions in the Democrats’ bill stem from the aftermath of the Russia investigation. During that inquiry, special counsel Robert Mueller and his team concluded that they were bound by a 1974 Justice Department policy memo that concluded a sitting president could not be prosecuted in office, limiting their ability to investigate Trump’s conduct and pursue obstruction of justice charges against him. The new bill would suspend the statute of limitations for crimes committed by presidents before and during their tenure to ensure they could eventually face consequences by future prosecutors.

Other measures would take aim at gaps in federal anti-corruption laws. Mueller’s team was hindered by Trump’s all but explicit offers of pardons to key witnesses like former campaign chairman Paul Manafort and longtime adviser Roger Stone. Trump subsequently followed through on his implicit promise by commuting Stone’s sentence and sparing him a prison term; Manafort is currently serving his sentence under house arrest after federal officials released him from prison, citing the Covid-19 pandemic. While Congress can’t limit the president’s constitutional power to issue pardons, the bill would explicitly include pardons and pardon offers as a “thing of value” under federal bribery laws.

Some provisions seek to reverse various defeats that Democratic lawmakers have faced in court. Federal judges have blocked multiple lawsuits by congressional Democrats and government watchdog groups to enforce the Constitution’s Emoluments Clause, which theoretically bans the president from receiving income from foreign governments. Wednesday’s bill incorporates that ban into federal law and provides a mechanism to enforce it in the courts. The bill also adds a number of measures to strengthen Congress’s ability to issue subpoenas, a critical dispute in Trump’s impeachment and Senate trial. In August, a federal appeals court dealt a grievous blow to Congress’s current subpoena power in one of the lawsuits from that dispute.

For those who opposed some of the Trump administration’s more procedural scandals, Wednesday’s bill is a welcome reform. The proposal would revise the law that governs how “acting” officials can serve in Senate-confirmed jobs, which Trump used to install pliable underlings throughout the Department of Homeland Security and other key agencies. It adds new protections for whistleblowers like the one whose complaint led to Trump’s impeachment by the House last year and for inspectors general, many of whom were purged after Trump’s acquittal in the Senate earlier this year. And after the Trump administration’s spree of Hatch Act violations over the past four years, the bill would finally give some teeth to its rules against politicizing government jobs and resources.

The Protecting Our Democracy Act is not the first time that Democrats have unveiled sweeping legislation for a post-Trump era. Shortly after taking office two years ago, House Democrats passed a major anti-corruption bill known as H.R. 1 that would make major changes to federal campaign finance laws, abolish partisan gerrymandering in congressional races, require presidential candidates to publicly disclose 10 years of tax returns, and impose a variety of other ethics and voting rights reforms. Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren and her allies proposed a bill in 2018 that would create a wave of new restrictions on lobbying and entrench some regulatory practices that could be struck down by the Roberts court over the next decade.

There are still some notable gaps in Democrats’ proposals. Wednesday’s bill would reform how presidents can declare national emergencies and spend money against Congress’s wishes; Trump infamously used those powers to bypass Congress in 2019 and fund a border wall without lawmakers’ permission. But party leaders have also avoided tackling a deeper overhaul of federal immigration laws that would address the extreme level of discretion currently given to the executive branch. That discretion allowed Trump and his allies to expel hundreds of thousands of immigrants and all but suspend asylum laws, despite public and congressional opposition.

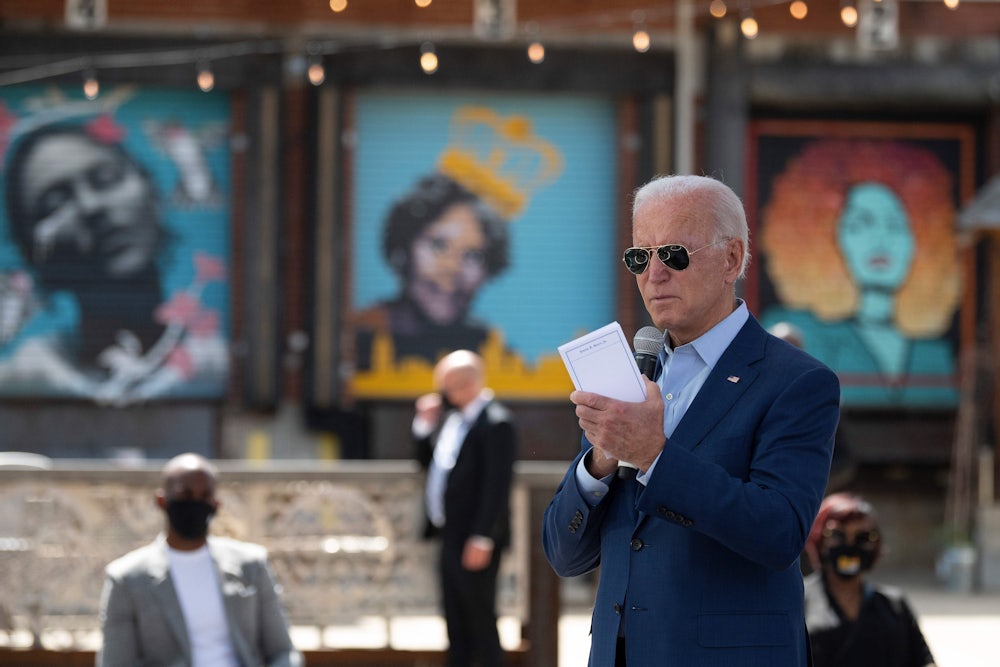

Nonetheless, the bill is a promising sign for how Democrats might handle the necessary work of post-Trump reforms. There is virtually no hope that Trump would sign the bill while he remains in office; the chances that it would even get a floor vote under Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell are just as slim. Its hopes instead lie with a potential Biden administration and a potential Democratic Senate majority that could emerge in November. If nothing else, the bill underscores how Joe Biden and the Democrats aren’t just trying to capture the presidency in this election but substantially reform it as well.