Susanna Clarke is the author of two literary legends. The first is fictional. In Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell, her 2004 debut novel, Clarke created an alternative England where magicians conjure warships out of the rain and walk through mirrors. The eponymous Strange and Norrell are gentleman scholars (and rivals) who restore the lost art of practical magic to early nineteenth-century England, only to find that they have unleashed forces beyond their control.

This first, fictional legend gave rise to a second, true one: the unlikely story of how Clarke came to write it at all. In a 2004 interview with The New York Times Magazine, Clarke recalled that she was teaching in Bilbao, Spain, when she had “a kind of waking dream” about a man who had “been dabbling in magic, and something had gone badly wrong.” After returning to the U.K. in 1993, she took a short writing workshop with the fantasy and sci-fi writers Colin Greenland and Geoff Ryman. She showed them a story called “The Ladies of Grace Adieu,” which takes place within the Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell universe but concerns the lives of Regency lady magicians.

Greenland sent the story to the author Neil Gaiman, a friend. “It was terrifying from my point of view to read this first short story that had so much assurance,” Gaiman told the Times. “It was like watching someone sit down to play the piano for the first time and she plays a sonata.” When Clarke eventually finished the novel and engaged an agent, in 2003, the book’s heft and supernatural themes made dollar signs flash in Bloomsbury’s eyes. The Harry Potter craze was then in its ascendancy, and with its close-enough magical topic, Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell earned Clarke a huge advance and an international publicity rollout. Upon its publication, Strange & Norrell sat on the New York Times bestseller list for over two months.

Clarke exploded into literary celebrity, then vanished. She published The Ladies of Grace Adieu and Other Stories in 2006, a collection of tales expanding upon the original piece that caused Greenland to pick up the telephone, but that was it. Now Clarke has explained the reason: 15 years ago, she fell down for no good reason. Ever since, she’s been affected by a difficult-to-diagnose fatigue syndrome causing migraines, exhaustion, and photosensitivity. After very dark years in the late 2000s, and extensive therapies, Clarke has now finished Piranesi, a novel whose title keen readers will recognize from her first book and which picks up the loose ends left in Strange & Norrell’s world.

Clarke’s two legends are beginning to merge into one. Having gone from the hustle and bustle of publishing a hit to living in seclusion, she has written a dreamlike follow-up to her busy, involved debut. From within the universe she constructed decades ago in her first writings, Clarke has taken the toughest problem of her own creation—what to do with all the otherworldly architecture she’s made possible—and turned it into an opportunity to explore the effects of trauma and dissociation on memory and identity.

Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell is a masterpiece of literary homage and subversion. Writing in the simultaneously sharp yet mannered style of Austen or Thackeray—even using vintage spellings like “chuse” for choose and “shew” for show—Clarke decorates her England with satirical scenes from parlors to Parliament. In Clarke’s parallel England, sorcery was common in the medieval period, when a mysterious King Arthur–like figure called the Raven King ruled the north for several centuries before disappearing. Like the fantasy literature of J.R.R. Tolkien or C.S. Lewis, who were both professors of medieval English literature, Strange & Norrell is rooted in the canon of Arthurian myth, which gives the reader the odd sensation of rediscovering something old rather than consuming something new.

Though Strange and Norrell are scholars, they enjoy plenty of macho glory when they assist Wellington in the Napoleonic wars by causing, among other phenomena, ghostly angels to brandish spears at the enemy. But in the fullness of time (the novel is 800 pages long) the most important subplot turns out to be about a malevolent fairy who wreaks havoc when nobody’s looking, bewitching several women and a Black footman named Stephen. These are people and events whom the clever magicians consider unimportant, so it takes them most of the novel to figure it out.

Far from exulting in England’s imperial past, therefore, Strange & Norrell turns it inside out. By making her magicians insensitive clods who continually miss the point, Clarke caricatures the hubris of the English gentlemen who led the Industrial Revolution with their “magical” inventions, gaily mechanizing society out of all recognition without thinking too much about its less salutary aspects—like, say, the colonization of half the world.

In her 2004 Times interview, Clarke pointed out the difficulty in picking up where she left off, with Jonathan Strange traveling through a magical dimension of interconnected passageways called “the King’s Roads.” “I have a bit of a problem now that the fairy roads are all open,’’ she said. “What do I do with them?’’ Her answer, seemingly inspired by her years of seclusion, is an abstract and deeply moving story that begins with the idea of reading this magical system of passages as a metaphor for the human mind.

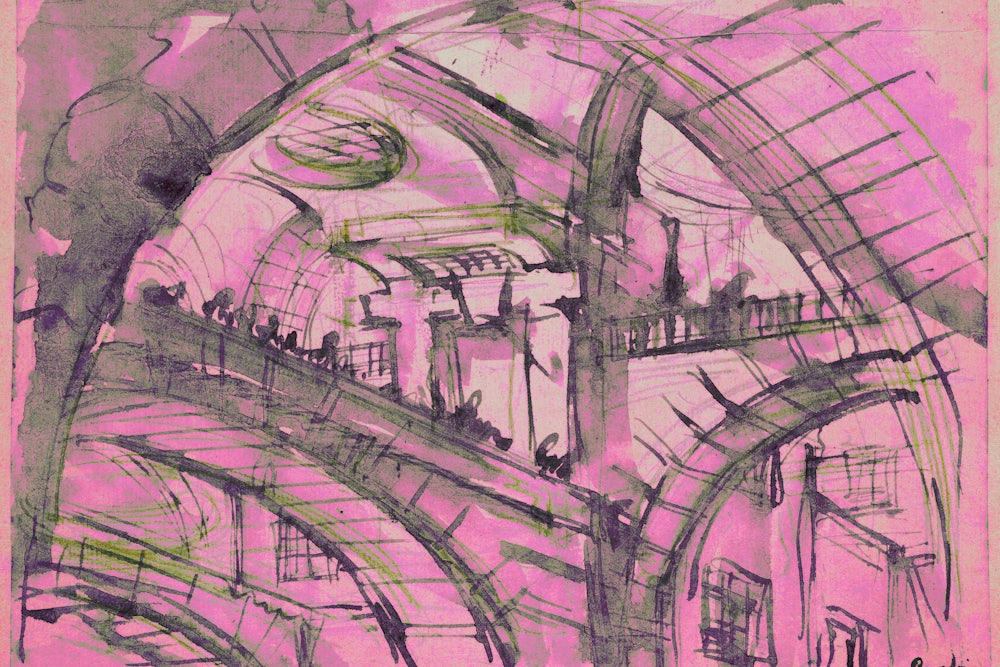

The title of her new book is a reference to Giovanni Battista Piranesi, who pops up in Strange & Norrell when Jonathan Strange commissions engravings of the King’s Roads. “They shewed great corridors built more of shadows than any thing else,” Clarke writes. “Dark openings in the walls suggested other corridors so that the engravings appeared to be of the inside of a labyrinth or something of that sort. Some shewed broad steps leading down to dark underground canals. There were drawings of a vast dark moor, across which wound a forlorn road.” These engravings, Strange complains, look too classical, and are too much “like the works of Palladio and Piranesi.” The first was a Renaissance architect and the second an artist of eighteenth-century Italy renowned for his etchings of surreal and infinite-seeming built environments, popularly known as his “prisons.”

Piranesi opens with a note dating a diary entry: “When the Moon rose in the Third Northern Hall I went to the Ninth Vestibule.” A man named Piranesi lives within these halls, which he numbers in detail in this journal. Tides of water rise and fall through them at fixed intervals, leaving mussels and seaweed in their wake, which he eats. He spends his time contemplating the only other people he knows to exist—several piles of bones, himself (“I believe that I am between thirty and thirty-five years of age. I am approximately 1.83 metres tall and of a slender build”), and a man “between fifty and sixty” whom he calls The Other. Clarke has Piranesi capitalize odd words—“I pictured Myself transformed into an osprey,” he recalls, for example, “flying with the other ospreys over the Surging Tides”—but her language here is more Samuel Beckett than Jane Austen, and the effect is unsettling.

Piranesi insists that he knows nothing of the world beyond these strange, wet halls and is intent on discovering more about his situation. But he seems to suffer some kind of amnesia, and he resorts to attempting to decipher the abstruse symbols that are everywhere around him in the form of statues and the Other’s mysterious utterances.

The eerie halls strongly recall the abandoned kingdom of Charn that appears in C.S. Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew, as well as the enchanted wood full of pools that leads that novel’s young protagonist there from England. Clarke mentions both places in a recent New Yorker interview, explaining that when she was very ill, it was their magical silence that appealed to her: “I found having people in the same street with me quite difficult to deal with,” she said. “Imagining that I was in Charn, that I was alone in a place like that, endless buildings but silent—I found that very calming.”

In her new novel, the silence of illness and seclusion becomes the blank areas of memory that our conscious mind can repress. This investigation into consciousness through water and stone is pure Freud. As Janet Malcolm wrote in her 1992 book The Purloined Clinic, “Freud’s concept of the unconscious is poised on an opposition between the durable and the mutable. What is unconscious is timeless, of stone, forever, and what is conscious is transient, ephemeral, written in water.” Freud often described psychoanalysis as a process of “wearing away,” a dynamic interaction between materials that Clarke turns into the conditions of Piranesi’s existence. She turns it into an atmosphere: an albatross lays eggs, distant waters thunder, the statues stare down at Piranesi from the walls.

Slowly, a parallel story emerges from the blanks in the narrator’s mind. By the novel’s end we know who this man is, how he got here, and—finally—the identity of his rescuer, who strikes out into the watery halls armed only with a lantern to find him. If Strange & Norrell was a long inquiry into the substance of Englishness, from deep national myth to petty table manners, Piranesi shows the inquirer turning away from social themes and toward more slippery, psychological questions, in order to produce a novel a fraction of the length but with quadruple the seriousness of its predecessor. Piranesi is a story about transformation and the work of a thinker, transformed: Susanna Clarke has fashioned her own myth anew and enlarged the world again.