Hari Kunzru’s Red Pill is a ghost story. It’s different, though, from Kunzru’s previous book, 2017’s White Tears, a parable of race in America with a (genuinely frightening) supernatural dimension. I mean more that the author’s new novel is haunted—as every cultural product of our time seems destined to be—by the specter of Donald Trump. While Red Pill isn’t overly preoccupied with his persona (it concludes on the night he wins the 2016 election), it aims to comprehend the culture that gave rise to him. It’s historical fiction, grappling with the past to illuminate the present.

Red Pill’s nameless narrator is, like Kunzru, a writer of Indian descent who lives in Brooklyn with his family but travels to Germany for a prestigious fellowship. (The novel’s Deuter Center for Social and Cultural Research feels like the American Academy in Berlin, where Kunzru was a fellow in 2016, dressed up for fiction.) Success has made the protagonist complacent, and he’s not altogether committed to his idea for a new book, on “the construction of the self in lyric poetry.” Portents hang over the novel’s early pages. “Our very happiness made me uneasy,” he says of his wife and their daughter, and it’s clear that more unease lies ahead. He stays up at night, “worrying about money and climate change and Macedonian border guards.”

Arriving at the Deuter Center, the narrator explains that the fortune endowing his intellectual labor was garnered by a savvy industrial chemist who made the world whiter.

Titanium Dioxide, the ubiquitous white pigment that brought light into the darkness of Germany’s postwar domestic spaces. There were pictures of Deuter examining gleaming white bathroom tiles, white painted walls, white plastics, toothpaste, Deuter chatting to young women working at conveyor belts strewn with white tablets.…

On his first morning at the center, he meets a helpful local, who informs him that one of the neighboring buildings, hidden among the trees, was the venue of the Wannsee Conference:

I nodded and said I had heard of it, but he felt the need to complete his explanation. “Where the final solution to the Jewish Question was planned in 1942.” Politely I looked in the direction he indicated. The house was too far away to see clearly.

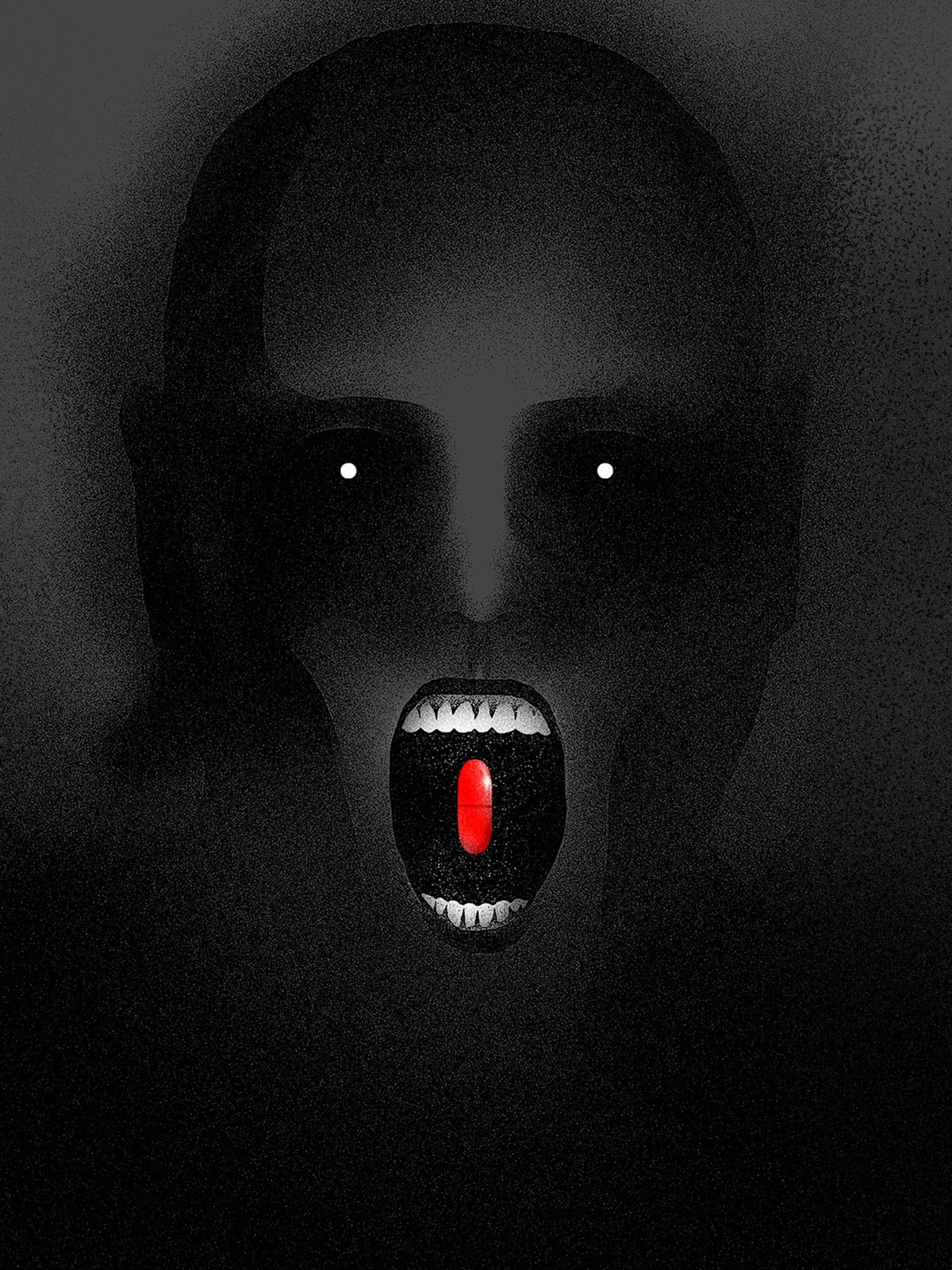

Clarity is what the narrator desires. His European sojourn brings him into contact with those who believe they have found it: that they can see through the pall of history, through liberal propriety, to the world as it is. The book’s title is a reference to a scene in the 1999 film The Matrix, in which ingesting a red pill liberates the hero from the trap of a simulated world. The red pill is a potent image for our meme age, used to describe an awakening. For the libertarian, the contrarian, the crank, the cult adherent, the men’s rights activist, the self-styled iconoclast, it’s a turn away from society and its norms. In The Matrix and in dark corners of the internet, this might look like truth; in wider parlance, the red pill is less about revelation than radicalization. Will this narrator swallow this metaphorical pill, and what will he see if he does?

Red Pill’s narrator is bothersome. He’s unwilling to meet one of the Deuter Center’s main requirements of its fellows: Instead of working in the common space set aside for them, he retreats to his lodgings to write. He cannot even bring himself to dine with the group. “The empty cups and cereal bowls triggered all my most misanthropic impulses.” He’s grand, consumed with thinking about Heinrich von Kleist, and self-important even in his self-doubt about his work (“Why had I not chosen to do the things that men do?”). The center asks him to have his irises scanned for security purposes, and he hesitates. There’s an intimation of something sinister in the stately home turned temple to ideas—vigilant staff, watchful cameras—but this is a feint. “Every writer knows about Chekhov’s gun,” the narrator teases us, leaving that weapon on the mantel.

Unable to lose himself in his work, the narrator turns to the true opiate of the masses. “I’d been watching a lot of television drama in Berlin, often several hours a day, retreating from formlessness into soothingly tight plotting.” His drug of choice is a series called Blue Lives (echoing that meaningless riposte to Black Lives Matter): “The show’s cops were all members of a special unit and they’d lost their moral compass. They were now as bad as the criminals they were pursuing.” The novel’s synopsis of this imagined show features dirty cops helping themselves to a drug dealer’s money, torturing a suspect not in search of a confession but to punish him. The gore-spattered antihero detective pushes a drill into a man’s mouth, then pronounces, “The whole earth, perpetually steeped in blood, is nothing but a vast altar on which all living things must be sacrificed without end, without restraint, without pause, until the consummation of things.”

The fact that Red Pill’s narrator reads into this program some special meaning feels less like insight than madness. “Everyone—criminals and police—was in high-stakes competition with everyone else, committing acts of appalling violence.” He understands this is not the subversion of a trope (the key to prestige television), but “a subtext smuggled into the familiar procedural narrative.” What if it’s not an escapist fantasy but a depiction of the world itself, a grim place inclined to violence and chaos, morality mere illusion? “Blue Lives felt threatening. Threatening to me, to me personally, to who and what I was, to the people I loved.”

Those earlier worries about climate change and the migrant crisis collide with the vision of society proposed by Blue Lives. Is it paranoia to be tormented by the world we’ve made? He telephones his wife: “I think this is what Weimar Germany must have felt like. The sense that something was coming. We have to expect the unexpected. A Black Swan event.” His fears might be a symptom of derangement if he weren’t right. The narrator senses that “the internet had changed things,” and that politics, now, is more about “feelings, atmospheres, yearnings, threats” than ideas. To unlock the politics that Trump embodies—the post-globalism tribe of the red MAGA hat, the alt-right’s thrall to blunt and inelegant power—and convey the quotidian experience of life right now, Kunzru settles on a metaphor: madness.

Another of the Deuter fellows drags the narrator to a party, and, in one of those unlikely turns you accept in a novel, he meets Blue Lives’ creator, an American screenwriter called Anton (he also uses the name Gary; I’m not sure what to make of the Latinate sound of what might be a pseudonym or what might be a middle name). He presents himself as a well-mannered intellectual heretic, a plausible composite of Jordan Peterson, Ben Shapiro, and Steve Bannon. “Only when we were standing at the bar did it dawn on me that I knew exactly who he was. And I was afraid.” The narrator wants to discuss the show’s intellectual subtext—“Heraclitus. Schopenhauer. Emil Cioran.”—and Anton is flattered.

The show’s creator acknowledges the program’s references to Joseph de Maistre, the political philosopher who argued a politics of authority instead of reason: “You can’t have a state without the threat of violence. It’s the only way to get people to obey. The executioner is that threat.” The narrator’s concern about Blue Lives’ subtext is warranted: Anton’s vision of the world is a warped one, fetishizing power and disdaining the vulnerable, all suffused with a loathing of multiculturalism. The two dine in a restaurant with some other friends, and as Anton ventures further (it’s a slippery slope!), we land on antisemitism and xenophobia:

“Greg’s another crusader. He’s from LA, like me, so we essentially grew up knee-deep in Jews, but we both have a feeling for our heritage. And here’s another thing. My friends have an aversion to being told what to do. To having things forced on them. Karl doesn’t like his culture being polluted by immigrants. Tara doesn’t want to have to worry about rape. Greg just doesn’t like spicy food. The question is do Greg and Anton and Tara have a right to their preference?”

When the narrator dismisses this “just asking questions” routine, Anton indicts his umbrage as hypocrisy:

“Your weakness,” he added, turning back to me, “is that you’re always surrounded by people who think just like you. When you meet someone who your silly shame tactics doesn’t work on, you don’t know how to act. I’m a racist because I want to be with my own kind and you’re a saint because you have a sentimental wish to help other people far away, nice abstract refugees who save you from having to commit to anybody or anything real.”

I understood this scene as the novel’s red pill moment. Not because it ends with the narrator persuaded by Anton’s vision of the world. Indeed, this conversation builds the narrator’s resolve to reject those politics thoroughly. But it’s the moment of epiphany, the narrator comprehending the limits of his vague liberalism, understanding that there are others who not only reject his worldview but see another reality altogether. He knows that reality, while there are many perspectives on it, is rooted in objective fact, that the sci-fi mumbo jumbo of The Matrix does not translate to our politics, and that Anton’s red pill world is a vicious illusion. And yet he can’t say why he is so captivated by it.

From this point, Red Pill wanders, rather like a prestige television show after a bravura first season. Anton recedes, less a character than an animating force, his condemnation of the narrator made into prophecy. Stung by Anton’s words, the narrator enacts them. First, in a well-intentioned but absurd turn, he tries to intervene in the life of a refugee he spies on the streets of Berlin. This echoes his earlier attempts to forge a connection with Monika, a woman who works as a maid at the Deuter Center. A chunk of the novel is given over to Monika’s memories of life in the former East Berlin, where she was a punk and radical, then a collaborator with the national security services. It’s a digression and feels too pointed—the state brutalizing its citizens for no particular reason—and too long, like a multi-episode arc on a television show focused entirely on some guest star.

The novel abandons logic to reveal the illogic of Anton’s worldview. The pace quickens, and the narrator bounces around Europe, but this action feels more like fever dream than story: overly constructed, too deliberate, occasionally silly. The narrator follows Anton to Paris, loses time tracking reactionary discourse on the internet, and finally travels to Anton’s retreat in the Scottish Highlands, meaning to confront his enemy or perhaps commit suicide, believing himself to be in the man’s control somehow, either brainwashed or just thoroughly shaken by exposure to his radical ideas. Kunzru is an able storyteller; outlandish plot or not, I did not read so much as binge. The series finale was only pages away; how the hell was he going to wrap this all up?

Kunzru takes us to 2016, of course: The only possible conclusion to this fable about the emptiness of right-wing blather is the election of Donald Trump. There’s an abrupt break in the narrator’s European adventures—think of it as the end of a dream sequence—and we find him back in Brooklyn (“Everything about the apartment is the same, but everything is different. I feel like Odysseus.”) after having been captured by the police and sent to a mental hospital. (I told you the plot was outlandish.)

It’s unclear whether this was a psychic break or intellectual crisis, but the narrator is mostly returned to himself, if dogged by the sense that his life of bourgeois comfort—arranging cheese plates, seeing a therapist—is an illusion.

The streetscape wasn’t real. The sidewalk, the passers-by, the clouds in the sky, all were elements in a giant simulation. The sunlight was not sunlight but code, the visual output of staggeringly complex calculations.

Red Pill’s final set piece has the narrator and his wife host a party (complete with lesbian neighbors) to watch Hillary make history. The guests depart after Florida is called for Trump; the narrator and his wife watch the news, unable even to talk to each other. It’s discomfiting because I—as most readers of literary fiction—am the sort of person Anton would hate. Like the narrator and his wife, my spouse and I spent the night of the election in stunned silence. Of course, another reality is unfolding elsewhere. For people who hold a very different set of beliefs about the way the world works, it’s a moment of triumph. “Already, the shitposters on the message boards are grabbing images of crying Democrats. We drink your salty tears.”

Late into the night, watching a live stream of a victory party, the narrator spots his tormentor on screen: “What Anton and his capering friends in their red hats call realism—the truth that they think they understand—is just the cynical operation of power.” It’s the only fitting conclusion to the novel, but it’s dissatisfying. Kunzru can’t accomplish a rebuke of Anton’s worldview not because he’s not a gifted novelist but because it’s already evident that the Steve Bannon mythos is a hodgepodge of prejudices, fears, and misinformation. Nor can the novelist answer why liberals have granted this claptrap such power.

Kunzru posits this crisis as illness, as mental break. It’s a valiant attempt to literalize the troubles with the liberal left, but we’re not the crazy ones. Yes, it’s true that Anton, and Trump, and so many I could name, care only about “the cynical operation of power.” But we knew that in 2016.