For all the effort expended over the past 15 years to bring punditry a step or two closer to the social sciences and into communion with statistics, the art of the political take is still, for the most part, the art of the quick draw. Our discourses and the technologies that now sustain them aren’t built to reward patience; as ever, the loudest and most important voices are those that can mold their predictions out of raw, uncomplicated intuition with speed and ease. Other, more careful and more interesting voices root their arguments at least partially in scholarship about our political past. But even they might be led astray by historical determinism: the presupposition of outcomes that representative data in the present has yet to reveal. As ever, the very best way to suss out what’s going to happen in American politics is to wait and see what happens. It’s not really foolproof—those who are loud and wrong about what will happen are often as loud and wrong about what’s happened already—but compared to the other methods, it really cannot be beat.

We’re a little under two months out from the election and a little over three months into a season of protests against racism and police violence that, despite what their critics have said, really have been mostly peaceful. A series of polls taken in June suggested between 15 and 26 million Americans demonstrated against the killing of George Floyd that month—if most had been committed to or engaged in violence, the president and the right would probably have more to fear now than a mere loss at the polls in November. Of course, there genuinely has been looting and rioting in cities across the country. For several nights in late May, the nation watched sections of Minneapolis go up in flames. And as it was happening, we heard a lot about 1968.

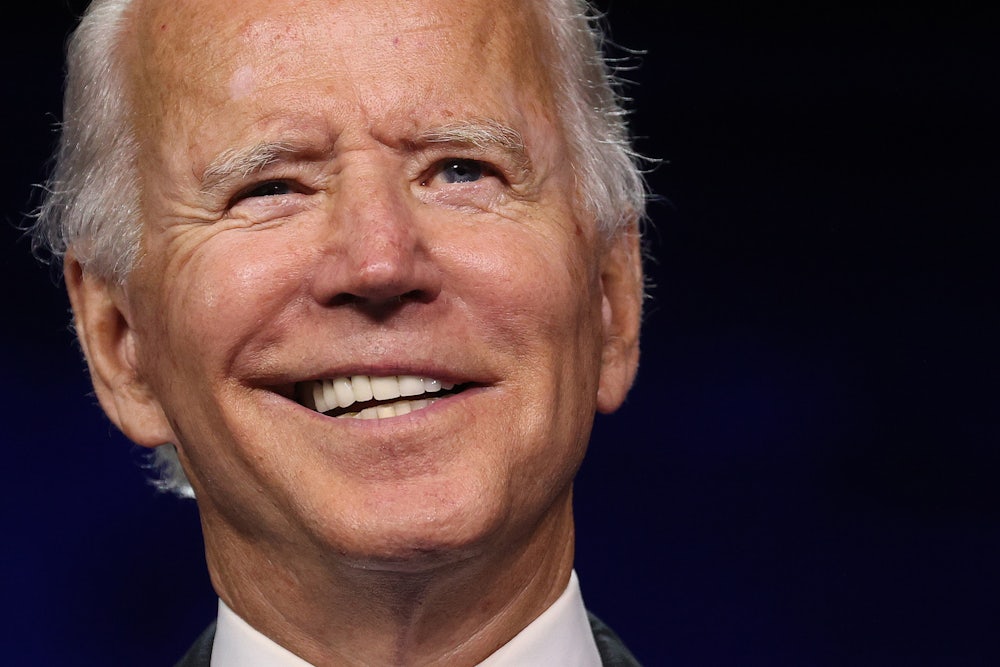

Our understanding of the impact the King assassination riots had on racial politics and that year’s election has been capsulized into a tidy piece of received wisdom, one invoked so solemnly and so often this summer it might have been thought a law of physics: Riots and disorder hurt Democratic candidates and help Republicans. But Biden’s continued rise in the polls after Minneapolis suggested strongly that this particular election, with these particular candidates, might play out differently. And now, after another round of high-profile protests, a Republican National Convention heavy with “law and order” rhetoric, and a wave of quality national and state data, we can say with some confidence that those who raised the alarm about the demonstrations have, so far, been comprehensively wrong.

The limits of the ’68 comparisons should have been obvious from the beginning. In the first place, the racial attitudes of the American public and the disposition of the mainstream press toward racial protest have changed dramatically over the last half-century. Our basic political geography has also changed, as has the composition and partisan sort of the electorate. And the “law and order” candidate this time around is a historically unpopular incumbent who has deepened the lawlessness and disorder he decries—an incumbent who, incidentally, has also bungled the response to a pandemic that remains at the top of mind for most voters and has killed nearly 190,000 Americans.

The Trump campaign’s decision to elide this last fact and lean fully into messaging about urban disorder during the RNC should have been seen universally as an act of desperation. Instead, a slew of pundits—spooked by the unrest in Kenosha, Wisconsin, following the shooting of Jacob Blake, not chastened in the slightest by Biden’s numbers post-Minneapolis—insisted that Trump had settled on a strategy sure to succeed absent a dramatic change in strategy from Biden who, just to shut people up, delivered his millionth denunciation of rioting in Pittsburgh and Kenosha this week. “It’s no use dismissing their words as partisan talking points,” The Atlantic’s George Packer wrote of the RNC last Friday. “They are effective ones, backed up by certain facts. Trump will bang this loud, ugly drum until Election Day. He knows that Kenosha has placed Democrats in a trap.”

Earlier this week, The New York Times’ Tom Friedman one-upped Packer with a wholly arbitrary figure on rioting’s supposed impact: “Every scene of rioting and looting,” he mused, “is probably worth 10,000 votes for Trump’s re-election campaign.” On Monday, the Times’ Bret Stephens accused progressives of “unthinkingly helping Trump” and referenced a recent book on looting that had upset some in his circle. “Many of these friends, I suspect, will reluctantly vote for Trump,” he wrote, “not out of sympathy for him, but out of disgust with defenses of looting and other things they see too often on the left.”

Anecdotes like this tell us nothing about the wider electorate, of course; Stephens doesn’t have that many friends. We can turn instead to a collection of polls released over the past week. According to FiveThirtyEight’s average, Biden leads Trump by over seven points nationally, 50.4 to 43 percent. And despite the right’s best efforts, the constituency of Americans who believe Joe Biden is in cahoots with the Black bloc remains small. According to The Economist and YouGov’s latest national poll, only 38 percent of voters believe Biden holds extreme views compared to 56 percent who say the same of Trump. That holds true even among the always critical over-65 set that the Trump campaign and the conservative press probably imagined they’d have an easier time scaring—unsurprisingly, polls have shown them to be more hostile to the protests and anxious about unrest than the electorate at large. Even so, 50 percent of them say Trump holds extreme views, while 37 percent say the same of Biden.

On the question of who’d best keep Americans safe, CNN’s latest poll shows Biden ahead of Trump 51 to 45 percent. Among those 65 and over, Biden leads again, 54 to 44 percent. Quinnipiac’s latest finds 50 percent of likely voters and a 46 percent plurality of those over 65 believe they’re less safe with Trump as president. A 42 percent plurality of likely voters and a 46 percent plurality of those over 65 believe they would be safer with Biden as president.

Moreover, 52 percent of voters disapprove and 42 percent of voters approve of Trump’s handling of “crime and criminal justice” specifically, according to The Economist and YouGov. Similarly, 55 percent of voters say Trump’s handling of crime makes them “uneasy,” to the 39 percent who express confidence in it. By comparison, Biden is underwater on the issue by just one point—44 percent “uneasy,” 43 percent confident. And CNN’s poll reports too that 62 percent of Americans overall, 58 percent of those over 65, and 68 percent of whites without college degrees—the Trumpiest of demographic constituencies—aren’t worried about crime in their communities to begin with.

These are all national numbers, and they wouldn’t mean all that much if they didn’t hold true in the swing states likeliest to actually decide the election—but they appear to. It should be old news by now that the ballyhooed decline in support for Black Lives Matter in Wisconsin—likely the consequence of a repolarization around the protests that didn’t actually reduce net support for the movement—also didn’t correspond at all with Biden’s lead in the state, which continued a fairly steady rise. Now we can say that the unrest in Kenosha hasn’t put a real dent in Biden’s standing either. On Wednesday, the day before he set foot in Kenosha for an address on the violence, Biden led Trump in FiveThirtyEight’s average by 7.2 points: 50.2 to 43 percent. On August 23, the day Jacob Blake was shot, Biden led by seven points: 50.1 to 43.1 percent.

In Pennsylvania, by contrast, there’s real evidence that the race has tightened in recent weeks. Biden currently leads in the average by just over four points: 49.4 to 45.3 percent. A month ago, Biden was ahead by almost seven. Evidence that Trump’s “law and order” messaging is deeply resonating in the Keystone State? A set of very granular and specific questions from the latest Monmouth poll suggests not. “How much of a problem do suburban communities face today,” one item asked, “because of different people moving into nice neighborhoods who may bring in crime and lower property values?” A 52 percent majority of Pennsylvania voters responded that it isn’t a problem at all, including 52 percent of whites without college degrees, a 49 percent plurality of voters over 65, and, remarkably, a 49 percent plurality of voters in counties Trump won by over 10 points in 2016. When asked how worried they were about crime and lower property values being brought to their own particular neighborhoods, a full 74 percent of Pennsylvania voters replied that they were “not too” or “not at all” concerned, including 66 percent of voters over 65, 75 percent of noncollege whites, and 75 percent of those in deeply pro-Trump counties.

None of these numbers should be taken as indication that Biden has nothing to worry about. Although Trump hasn’t been able to pin him on the riots and Biden continues to lead in polling on coronavirus, character, and uniting the country, he still isn’t doing especially well on the economy. A 48 percent plurality of registered voters believe it’s getting worse, according to The Economist and YouGov; CNN finds 58 percent of Americans are worried about the economic situation in their own communities. Yet Trump is effectively tied or ahead of Biden on the economy in multiple polls—likely voters split 48 to 48 percent on who would handle the economy better in Quinnipiac, and CNN, which shows Trump with a net positive economic approval rating, has him a toe ahead of Biden on the issue: 49 to 48 percent. Trump is also tied with Biden on the economy among likely voters in Wisconsin, 46 to 44 percent, according to a Fox News poll.

All this seems mostly attributable to residual and misplaced credit Trump had gotten for the economic growth voters saw before the pandemic, as well as residual and misplaced faith voters still have in Trump’s economic know-how as an ex-businessman. But it also suggests Biden has yet to deliver a pocketbook message that really sticks—a task that ought to be easy enough for a challenger running against an incumbent who helped bring the country to an unemployment rate that now stands at over 8 percent.

It should be said that the political impact of the protests and riots may still change between now and November. The takeaway from all we’ve seen over the past few months isn’t that unrest and radical action are, always and everywhere, free of political cost. Rather, it’s that our current political commentariat can’t reliably inform us when and how those costs might be incurred. The underlying questions are too complex to be handled at our discourse’s normal speed; the many voices within it who allow their disdain for radicalism to cloud their analyses can’t be trusted to handle the issue carefully anyway. That’s a responsibility left to the rest of us.