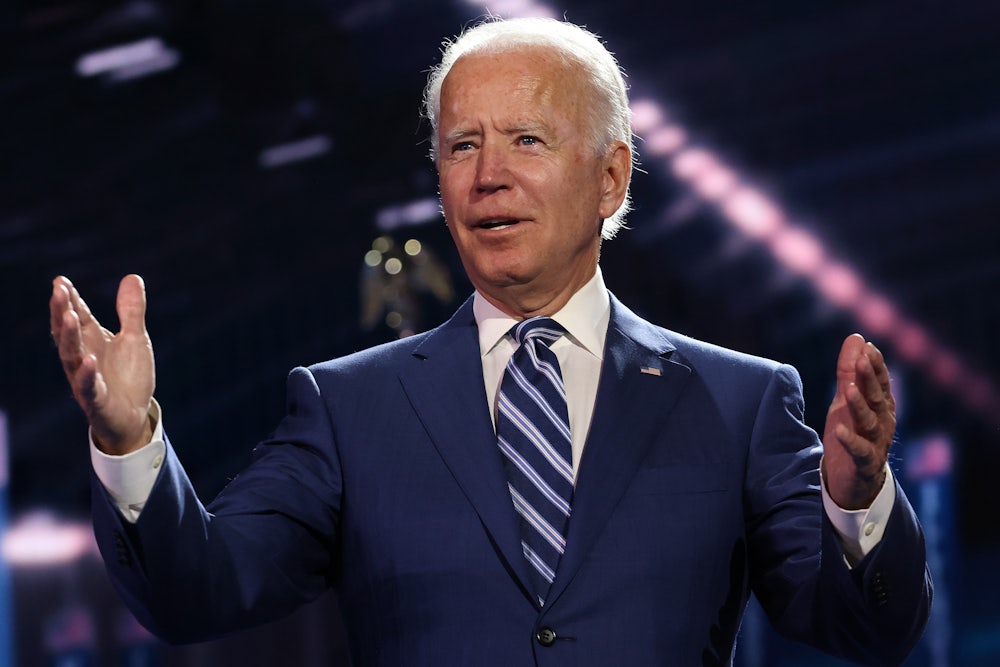

Joe Biden’s case for the presidency is not hard to understand; it may very well be the least complicated in modern American political history. He is not Donald Trump. He is, by contrast, a thinking, feeling person who engages with and cares very deeply about people who are not Joe Biden. A vote for Biden is a vote to stop a blood tide of madness and pandemic. As slogans go, “Build Back Better” is wanting, even by the abysmal standards of presidential politics, but here’s the good news: It barely matters. What really matters is that Joe Biden is not Donald Trump.

That’s a taut summary of the foundational ideas upon which the Democratic National Convention has been built. Biden, by virtue of not being Donald Trump, can get us out of the myriad crises that have enveloped the country over the past four years. Biden is the proud leader of a big tent party, so big that it contains many people with whom Trump would not associate or would actively demonize. It’s often the case that a presidential candidate with a long career in the Senate finds that those decades of experience are a weakness, a litany of choices and compromises ably weaponized against the would-be president. But for a not-Trump, like Biden, it’s a strength. Ol’ Joe! He knows how to grease the wheels of government to get things done.

And hey, Republicans like him! John McCain was his friend. The first two nights of the DNC were aimed, more often than not, at winning over Republicans who were disgusted by Donald Trump in order to convince them that Biden was a safe choice, a throwback to an earlier kind of Democratic Party, and that there was even a place in his big tent for them. Republicans John Kasich, Colin Powell, Christine Todd Whitman, Cindy McCain, and Meg Whitman launched a full-court press aimed at pushing those dozens of Republican fence-sitters out there in America toward Biden. “I’m sure there are Republicans and independents who couldn’t imagine crossing over to support a Democrat. They fear Joe may turn sharp left and leave them behind,” Kasich said, channeling Ralph Macchio by standing at a literal crossroads. “I don’t believe that because I know the measure of the man.” Kasich was vouching for Biden: He’s not like other Democrats.

On the third night of the DNC, the party finally turned toward those other Democrats. Its opening segments focused on issues that trouble the heart of the Democratic base, such as gun violence, climate change, immigration, and #MeToo—and they aimed to be melodramatic and emotionally searing. The underlying message of these segments and speeches blended with the ideas of the first two nights: Biden can hold this coalition together while delivering big, necessary change and solving the problems that have burned into our collective memory and which Congress has failed to adequately address for decades.

Despite how it’s often been characterized during the DNC, however, success is hardly a fait accompli. Mitch McConnell and congressional Republicans will assuredly work to stymie any and all reforms offered by a hypothetical Biden administration; it is almost certain that the federal bench Trump has assembled will work to thwart a Democratic president’s efforts. In a convention organized around the dangers of reelecting Donald Trump, there was little mention of the radicalism of the Republican Party or the impeachment of their standard-bearer. These are glaring omissions.

There is still a great deal of magical thinking—not just of a series of miraculous political transformations following a Trump loss in November but of a Biden administration walking into the Oval Office with a magic wand—happening at the convention. It’s an understandable indulgence, given the fact Biden’s election would, in some not insignificant ways, be a sudden sea change: Donald Trump would continue to be a boor and a chaos agent, but he’d be those things somewhere other than the White House. The worst excesses of his administration would be a thing of the past.

But this odd perspective permeated the proceedings in stranger ways. Throughout the night, the early days of Trump’s ascension to the Oval Office were remembered by various speakers not as the dire time of worry that they were but rather a tenuously hopeful moment when it was still possible for Trump to reveal himself to be fit to serve the nation. “If he had put his own interests and ego aside,” said Hillary Clinton, “if he had even tried to govern well and lead us all—he might have proved us wrong.”

Barack Obama gave voice similar regrets, saying, “I never expected that my successor would embrace my vision or continue my policies. I did hope, for the sake of our country, that Donald Trump might show some interest in taking the job seriously, that he might come to feel the weight of the office and discover some reverence for the democracy that had been placed in his care.” Four years ago, at a different Democratic convention, both Clinton and Obama seemed much more assured—and much less hopeful—of what Donald Trump’s election would entail.

And this magical thinking has crept into Biden’s pitch to voters. It is, to some extent, hard-wired into the back-slapping dealmaker’s DNA. Last year, Biden proclaimed that the world would “see an epiphany occur among many of my Republican friends” if he were elected president, that they’d be transformed into felicitous partners in a stately debate. It was a shocking notion coming from someone who had served as Barack Obama’s vice president, where he witnessed the extraordinary obstinacy of Republicans firsthand.

Biden and his fellow Democrats are, to their credit, clear-eyed about the challenges they would inherit at the end of a Trump presidency. The candidate has recently been invoking the idea of a “Second New Deal” response to Covid-19 and its concomitant economic collapse. But Biden’s campaign is rooted in the idea that he is a kind of political cheat code. As Vox’s Dylan Matthews found while interviewing Biden staffers, the Democratic candidate remains committed to the filibuster, a decision that will make any ambitious Democratic policy effort impossible. The idea that Biden might rely on parliamentary strategies, like budget reconciliation, to move big agenda items was pooh-poohed by his longtime economic advisor. Instead, Biden, we are told, will “leverage his relationships in the Senate to pass his agenda with bipartisan support.” With a raft of amenable Republicans behind him, the theory goes that he’ll bring about those changes that the modern Republican Party had hitherto done everything in its power, including shutting down the government on multiple occasions, to prevent.

But while it’s one thing for Biden to have supreme confidence in his Senate Cloakroom Backslap Game, it’s entirely different when other Democrats with more familiarity with the Republican truculence of the past few years, or a higher exposure to their more recent radical strain, indulges the same ideas. On the second night of the convention, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer presented a sixty-second laundry list of everything a Biden presidency was going to bring about.* To hear Schumer tell it, almost no problem would go unsolved: “With President Biden, Vice President Harris, and a Democratic Senate majority, we will make health care affordable for all; we’ll undo the vicious inequality of income and wealth that has plagued America for too long, and we’ll take strong decisive action to combat climate change and save the planet.”

Sounds easy! And by the time the third night was finished, the portfolio had expanded considerably: infrastructure, voting rights, racial justice, gun violence. “I love a good plan, and Joe Biden has some really good plans,” said plan-expert Elizabeth Warren, speaking to Biden’s child care plan, in case anyone was wondering if he’d forget to fix that as well. And throughout, the coronavirus pandemic and its subsequent, related economic collapse was never far from mind.

Clinton and Obama, like many of the convention speakers who’d preceded their own Wednesday night testimonials, situated Biden’s ability to solve these problems in his personality. “As the saying goes, the world breaks everyone at one point or another, and afterward many are stronger in the broken places,” Clinton said. “Joe Biden knows how to heal because he’s done it himself.” Obama, who played up his famous friendship with his vice president as if their relationship was the bridge over which he might impart his legendary mystique, at least acknowledged that Biden would need the help of other people to heal the nation.

Channeling John F. Kennedy, Obama declaimed, “Here’s the thing: no single American can fix this country alone. Democracy was never meant to be transactional—you give me your vote; I make everything better. So, I am also asking you to believe in your own ability—to embrace your own responsibility as citizens—to make sure that the basic tenets of our democracy endure.” The vast majority of those who will flock to vote for Biden will need considerably more guidance to provide the means by which he might overcome either Republican intransigence or an enduring Trumpian judiciary designed to provide Republicans with enough power in absentia to endure, or even thwart, a Biden presidency. So far, Biden’s vision of backroom comity and old-school bipartisan consensus building has left little room for a movement of committed citizens to imagine that they might have an important, daily role to play in the promised restoration.

Parliamentary war games, the fanaticism of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, the dire threat of a radical Supreme Court—these are not quite the stuff of a stump speech, let alone a party convention where the guiding idea is to rally voters behind an optimistic vision. But after three days of speeches, we know with precision what Joe Biden wants: a big tent to contain the Sanders wing of the Democratic Party and the Kasich wing of the Republican Party. In return, Republicans get a decent man and Democrats get progressive policy. Everybody gets no more Donald Trump. But these desires of Biden have been evident since the outset of his campaign. The piece that’s always been missing, and which will likely go unfound by the time the convention concludes on Thursday night with whatever Democrats come up with as its virtual version of a balloon drop, is the reckoning with reality and the plan for action. “We’ve got to do the work,” said Kamala Harris on Wednesday night. As some point, it may become necessary to explain how this work will work.

* This piece originally identified Chuck Schumer as the Senate Majority Leader.