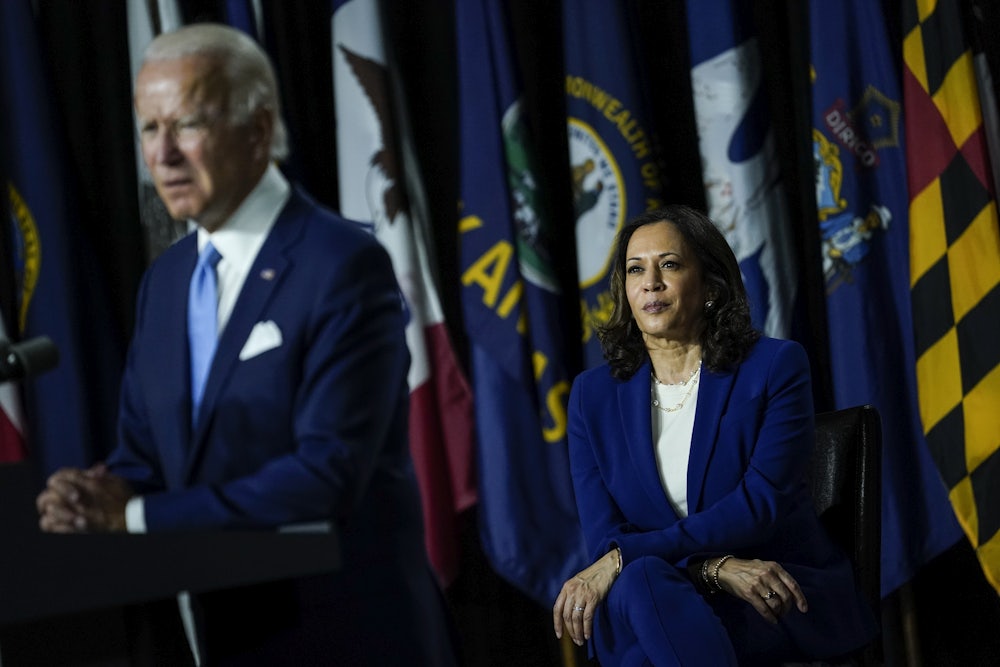

This summer, Wall Street made its peace with Joe Biden as the Democratic presidential nominee. If Donald Trump had spoiled the financial sector rotten for four years with tax cuts and regulation rollbacks, it didn’t take executives long to warm to Biden, who, after all, has his own record of voting to deregulate banks and slash bankruptcy protections. Now, according to the financial press, the investor class has been toasting last week’s addition of Kamala Harris to the Democratic ticket.

Since Biden’s announcement of Harris as his vice presidential pick, commentators have celebrated her as the first Black woman and first Indian American on a major party’s presidential ticket. But her political record, including when it comes to Wall Street, is somewhat more familiar when it comes to the top of the ticket. Like Biden, Harris openly courted Wall Street and Silicon Valley donors before and during the Democratic primaries and has enjoyed friendly relationships with various oligarchs since then. Whatever other qualities the Biden-Harris ticket holds then, on economics, it represents the Democrats’ return to their comfort zone of free-market fealty.

Runaway economic inequality and Bernie Sanders’s two back-to-back insurgent campaigns rattled the Democratic Party elite enough to generate some feints toward ideas like Medicare for All and higher taxes on the wealthy during the most recent primary season. (In 2017, Harris herself signed on as a co-sponsor of Bernie Sanders’s Medicare for All bill in the Senate but reversed her stance last summer on the campaign trail.) However, though they no doubt view the choice as strategic, the party’s decision to double down on its entanglement with Wall Street, which stretches back decades, will only compound the economic pain these ties have already created for millions of people in the United States, particularly as the majority of Americans struggle to exit a catastrophic recession that barely touched Wall Street. As The Washington Post’s Heather Long wrote last week, the downturn has essentially already ended for the rich but is certain to drag on for the bottom half of the income distribution, especially without sustained government intervention.

In the face of another four years of Trump, a Biden-Harris administration is probably our best chance for a workable recovery from the pandemic and the related recession. But whether or not a Biden-led recovery would do as much for the working class as it does for the rich is less certain. Biden, of course, oversaw the 2008 bank bailout as vice president and, while a Delaware senator, coddled the credit card industry. This election season, the campaign contributions he’s received from Wall Street surpass Trump’s, which doesn’t inspire much confidence for future crackdowns on corporate greed. In fact, he’s explicitly promised to avoid heavy-handed measures: “Corporate America has to change its ways,” Biden said at a July fundraiser hosted by financial executives but immediately added, “It’s not going to require legislation. I’m not proposing any.”

Harris, too, has her own murky record when it comes to the financial sector. As The American Prospect’s David Dayen has pointed out, though she’s touted her role in “going after” the big banks as California attorney general in the wake of the 2008 crash, her efforts in that regard largely amounted to a multimillion-dollar national mortgage settlement that served as yet another partial bailout for the banks with only minimal assistance for thousands of families whose homes had been foreclosed. During her tenure, her office also declined to file charges against OneWest—the bank run by Steven Mnuchin, now Treasury Secretary—for repeated violations of California’s foreclosure laws that resulted in the seizure of over a thousand homes.

In recent years, as an early co-sponsor of legislation like the Green New Deal and the Domestic Workers Bill of Rights, her record in the Senate has pointed to a willingness to back ambitious progressive policy. During the pandemic, she, Sanders, and Ed Markey introduced a bill for $2,000 monthly payments to individuals for the duration of the crisis. All of those are welcome counterbalances to Biden’s own time in the Senate. Yet, as Harris’s wavering on Medicare for All suggests, it’s still not entirely clear how committed she’ll remain to those ideals if she becomes vice president, particularly with Silicon Valley and the financial sector increasingly invested in her success.

Ultimately, the Biden-Harris ticket’s friendliness with Wall Street, even alongside their more progressive inclinations, represents a continuation of the Democratic Party’s long-running turn away from working-class voters, which culminated, at least partially, in the 2016 election of Trump. Despite interminable populist bluffing on the campaign trail, Trump was never remotely any kind of champion for the working class. At the same time, in 2016, enough voters in swing states felt moved to roll the dice on his middle-finger candidacy (or simply stay home) rather than throw in their lot with the Wall Street-anointed Hillary Clinton. With Biden-Harris, the Democratic Party once again seems intent on returning to the same unstable triangulation between cultivating corporate benefactors and appealing to ordinary workers.

Thanks mostly to Trump’s disastrous pandemic response, Biden now holds a considerable lead in the polls, but the Democratic Party’s ongoing abandonment of its working-class wing will likely have repercussions for future elections and for the fate of the U.S. at large. “The Democratic Party was never truly a workers’ party, but its major achievements of the twentieth century were possible only because it was a party of workers,” the historian Matt Karp wrote last year. “This alignment has been under stress since the 1960s. Today, it is officially dead.” That remains even more true now with the consolidation of the current ticket. While some things about Biden-Harris might be historic, the Democrats’ loyalty to the top, at least for now, is just more of the same.