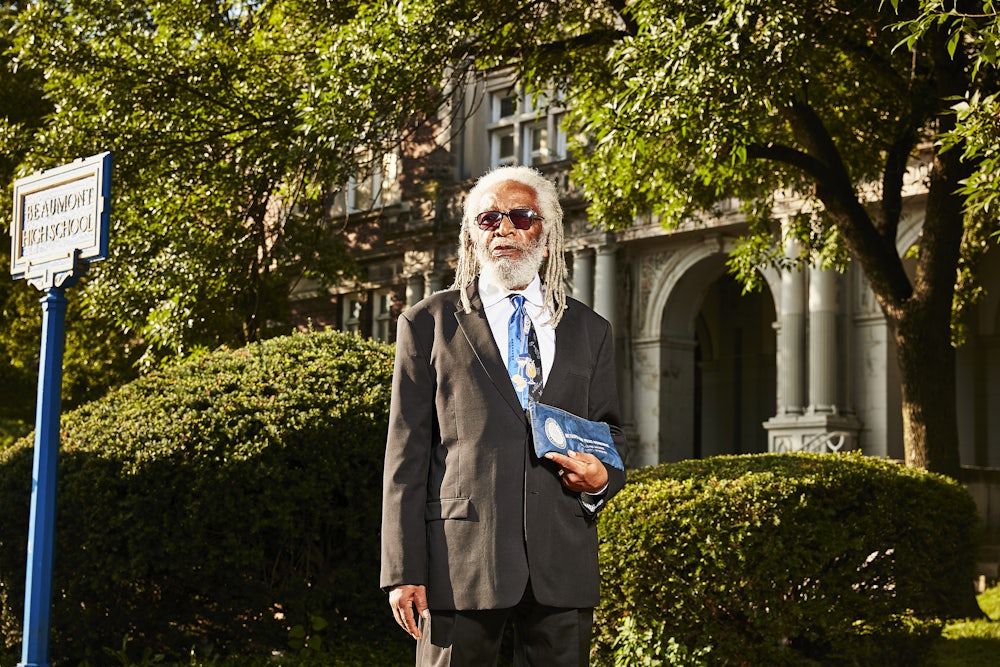

Bill Monroe, now 75 years old, completed his service in the U.S.

Army in 1967. The same year, he joined the St. Louis Metropolitan Police

Department. He told me about an altercation from those early years that has

stuck with him and that has taken on a special resonance this year, in the

midst of a once-in-a-generation debate over reforming American law enforcement.

“I was leaving the old Eighth District station,” he said, “and two white officers were bringing this brother they had in custody into the station. The brother was dressed real nice: double-knit slacks, silk shirt. Our eyes met. He said, ‘Brother don’t leave, don’t leave me, they’re going to fuck me up.’ But I went on and got in my car and drove off. Then something hit me, something told me to go back, and I did. Sure enough, they had beat him bloody, took off part of his ear, blood all over his slacks and shirt.”

Monroe lashed out against one of the officers. The two men, one white, one Black, fought right there in the station. Monroe described a vicious fight while other officers looked on. He later learned that the two white officers had stopped the Black man because he had been in a car with a white woman. They didn’t like that. It turned out she was his wife.

Monroe got a three-day suspension for the fight.

Those were different times, you might say. But when I was a young officer in the Eighth District in the 1990s, I had to physically restrain a white officer who had suddenly begun brutally assaulting a young Black man. We were standing on his porch. The young man was already injured, on crutches, leaning on them in the doorway of his home. He had committed no crime; he had merely refused the officer, who had no warrant, entry to his home. So the officer decided to kick his Black ass.

Attorney General William Barr claims that American policing does not suffer from institutional racism. Any Black officer will tell you that isn’t true. And I’m not only talking about an unarmed Black man being murdered by the likes of Derek Chauvin—a murder so vicious, so reprehensible, that it precipitated anti–police brutality protests across the world this summer. I’m also talking about the racist abuse that police in this country participate in daily, covering a range of harmful acts: violence, intimidation, trumped-up charges, plain old meanness.

And I’m talking about the racism against Black officers themselves. Over the course of his career, Bill Monroe carried multiple guns for his own protection—mostly from his fellow officers. This tension between white and Black officers has always been there, mitigated only by the personal relationships that develop between colleagues in a common space. But when something happens, that camaraderie falls apart. Quick.

Black officers know all of this. Many are looking to fight it. Thanks to the George Floyd protests, and now the protests in response to the police shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin, there has been a lot of discussion about how to “reform” the police. People talk about sensitivity training and accountability and oversight. Some talk about defunding the police altogether. Black officers across this country are talking about something different: about how to fight institutional racism and white supremacy from within police departments; about how to hitch their efforts to the movement for Black Lives and for a true account of our national origins in slavery and genocide.

Fairly or not, the onus has always disproportionately fallen on Black people, from the Civil War down to the civil rights movement, to make America more equal. The same could be said of one of the most pressing civil rights issues of our time: fixing the police.

When I was a police officer with the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department, I was always aware that the community that raised me, encouraged me, and loved me was my community. The fact that I became a police officer never changed that. It didn’t suddenly become “us against them.” I could say the same of the majority of Black people who I know who are formerly or currently in law enforcement. More than that, we are clear-eyed about the role that race plays in policing, and committed to eradicating racism and white supremacy from law enforcement and our criminal justice system.

We have to be. Our own lives and livelihoods are on the line. Take the example of Luther Hall, a Black police officer who was working undercover during anti-police protests in St. Louis in 2017. Without provocation, he was beaten so badly by at least four white police officers that it ended his career.

Or how about Milton Green, another Black St. Louis police officer. He was shot by a white officer in 2017 after he attempted to assist officers during a foot pursuit while he was off-duty. Out of uniform, he was ordered to the ground by an officer when he first appeared with his weapon. But he was subsequently identified and acknowledged as an officer by a detective at the scene. Then, while he talked calmly with the detective, another white officer walked up and shot him on sight. His injuries cost him his career. He was in danger of losing his home.

The city’s predominantly white police union, the St. Louis Police Officers Association, has shown nothing but indifference and contempt for these two victims of police brutality. The SLPOA is not unique in this regard: This is the way police unions across the country treat Black officers. Many a racist and white supremacist finds a home in a police union. There is no “All Blue” talk for Hall or Green. Police unions are responsive to Black officers when Black officers tangle with the Black community. Then they have something to say. Only then can union leaders put aside their pathological disregard for Black life.

Some reformers have called for the abolition of police unions, which have proved resistant to all kinds of reform and remain contemptuous of their democratically elected partners in civilian government. The problem with that argument is that we still need a collective response to police racism; we need collective power. We need a movement that includes Black officers from coast to coast. More than that: a movement that includes any group marginalized on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, or religion. Forming a critical mass of these officers and uniting with those standing up for Black Lives—our lives—should be our work and focus right now.

Sergeant Heather Taylor is a 20-year veteran with the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department, a supervisor with the homicide division. She is also the president of the Ethical Society of Police, the predominantly Black St. Louis police officers association. ESOP was formed in the 1970s by Black officers who recognized that the SLPOA would never represent their interests and, in many cases, would be outright hostile toward them.

I’ve known Sergeant Taylor for years: She has consistently been a voice for the Black community. And she has paid the price. The wife of a white officer once openly expressed hope that she bleed to death—a sentiment that she posted on social media and that was “liked” by many other St. Louis police officers. A former colleague who had been terminated from the department for domestic violence once told Taylor that if she ever found herself in a life-or-death struggle, she shouldn’t count on their help.

This came after Taylor called for former police officer Jason Stockley to be convicted for the 2011 murder of Anthony Lamar Smith. Stockley, who is white, was captured on video announcing to his partner, “I’m going to kill this motherfucker, don’t you know it,” during a pursuit of Smith’s vehicle. After Smith crashed his vehicle, Stockley walked up to the car and shot him multiple times, fulfilling his promise. He then retrieved an unauthorized gun from inside a bag in his police vehicle, brought it to Smith’s car, then put it back in his own car. All of this was caught on camera. Stockley’s defense, of course, was that Smith had a gun. But the gun Stockley “recovered” from Smith only had Stockley’s DNA on it, including on the screws used to assemble the gun. He was found not guilty by a white judge, and protesters took to the streets—the same protests that resulted in Luther Hall getting beaten viciously by his white colleagues.

The fight against police brutality is personal for Taylor. Her own aunt was killed by a St. Louis deputy marshal. A fierce critic of the police, she is an inviting target for defenders of the status quo, even more so because she is a Black woman asserting herself in a hostile space. She knows it’s not easy to stand your ground in the face of such pressures. When I asked her what she would say to Black officers around the country right now, she said, “First, recognize that you are Black, versus that ‘All Blue.’” She added, “Now more than ever, stand up. You might be the only one in the room standing up, but do it for the community.”

“Don’t be a part of the problem,” Bill Monroe told me, when I asked him the same question. “I would have forced Derek Chauvin off George Floyd’s neck.” One of the police officers involved in that incident, Alex Kueng, is Black; he now faces charges of aiding and abetting Floyd’s death.

Monroe added, “We have to be the change agents for the community. It’s ‘All Blue’ only if you go along to get along.” Most Black officers that I know acknowledge this is the truth.

Dr. De Lacy Davis is a former sergeant with the East Orange, New Jersey, Police Department. Along with myself, he is a founding member of the National Coalition of Law Enforcement Officers for Justice, or NCLEOJ, and a leading public advocate against racism in law enforcement. In 1991 he founded Black Cops Against Police Brutality, or B-CAP, to act as the conscience of the criminal justice system, to improve police-community relations, and to enhance the quality of life for Black Americans. He once had charges brought against him by the police union for saying, “The organizational culture of law enforcement is white male–dominated, racist, sexist, homophobic.” He conceded that “you might find a good cop” within that culture—but what can one good cop do in such an environment?

Davis is worried that the heightened awareness around police reform will not last, even among Black officers. More Black cops are speaking up publicly about the need for change, he noted, but it’s critical that they also speak up in private, in the confines of the station. “The reason I see more Black police officers standing up and speaking out is because white men have given them permission,” he told me, a reference to the growing number of white officers, especially among leadership ranks, openly (and finally) acknowledging institutional racism in law enforcement.

Davis also noted that history shows that the momentum for reform is usually short-lived. “In the ’60s we had riots over police brutality during the civil rights movement,” he said. “Rodney King was 1992, Mike Brown was 2014. Every 25 years or so, we see this seismic shift. We got about three more months of Black Lives Mattering until it becomes commercialized, sanitized, and popularized—then we bounce back to normal.”

Rochelle Bilal, also a founding member of NCLEOJ, made history this year when she became the first Black female ever elected sheriff in the city of Philadelphia. She was blunt about the role Black police officers should play in the reform effort: “Stand for what’s right or get out of the way. This is the civil rights movement of our time.”

After ending my career in law enforcement in 1999, I began working for the American Civil Liberties Union in St. Louis. I worked on a case representing a young Black man named Anthony Collins. In 2006, Collins had been brutally assaulted and maced by a police officer at a random DUI checkpoint. He had been in a hurry to reach his destination, and, unsure about the officer’s instructions at the checkpoint, got out of his car to ask for clarification. This action was deemed “noncompliance” by the officer, leading to Anthony’s assault. He was initially refused medical treatment; he was also subject to arrest. He was ultimately released with no charges when other officers at the scene realized that Anthony was a U.S. soldier; the assault had caused him to miss his flight back to Iraq for his second tour of duty there.

I remember talking to Collins about the incident. I remember his utter disgust and anger at how he and his family had been treated by police—not just during this one incident, but over the course of his whole life. Serving his country in a war zone didn’t exempt him from being Black in the eyes of American police officers. Nothing does.

Reform may come from the top. If history is any indication, it also may not. So what do we then? Alex Kueng, the Black officer who held George Floyd’s back while Derek Chauvin pressed his knee into Floyd’s neck, told his mother that he wanted to be a force for good in the Minneapolis Police Department. “That’s part of the reason why he wanted to become a police officer—and a Black police officer on top of it—is to bridge that gap in the community, change the narrative between the officers and the black community,” his mother told The New York Times. But when it mattered the most, when another Black man’s life hung in the balance, Kueng didn’t do the right thing.

Kueng is proof that Black officers have the same police power as white officers to abuse the bodies, rights, and dignity of civilians, very much including the people in their own community. He is why we call police racism a systemic problem, requiring a systemic solution. Black officers are going to have to be a part of that solution, working together, beyond the good intentions of any individual or any municipal government. They are going to have to recognize that salute-the-flag, stand-for-the-anthem, police-officers-are-all-heroes, performative patriotism that most of their white colleagues like to indulge in is meaningless when those white officers don’t think the Constitution protects their Black families and loved ones.

They can start now. Specifically, they can offer personal and professional testimony to spur reform legislation. What would this legislation look like? It would require real accountability—i.e., punishment—for those officers who violate the rights of citizens, up to and including murdering them. It would tackle the problem of crime holistically, by directing funds to communities in the areas of health care (including mental health), housing, education, employment, and violence-abatement programs. Legislators frequently cite “law enforcement support” for bad laws that hurt Black people; it is thus incumbent on law enforcement to show there is serious opposition to these laws.

Black police officers also have to ensure that the same old voices do not dominate public discussions of police corruption and brutality. Privately disagreeing with the ludicrous, aggrieved statements of police union leadership is not nearly as powerful as publicly stating that they don’t represent the views of Black officers. Some officers might mistake speaking up for self-aggrandizement—to the contrary, a stronger media presence helps frame issues accurately and prevents the public from being misled by imposing men in uniform. Black officers should also consider dropping their membership in any union that pushes them to stand against their community and support, tacitly or otherwise, the extrajudicial abuse of it.

The go-to argument of corrupt cops is that the reformers just don’t understand the work, or appreciate the dangers involved. Well, Black police officers do understand the work. We understand a lot more than that, too. It’s time for us to add our voices to a movement for genuine criminal justice reform—for transformative change centered on eradicating racism. Our effort is not only important. It is required.