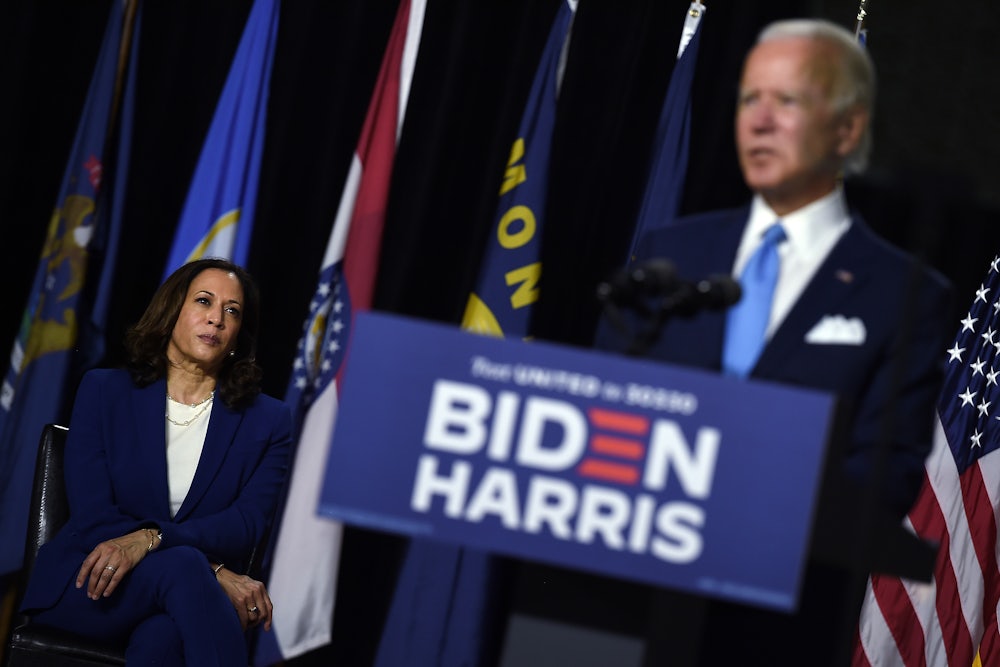

On Tuesday, Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden officially announced California Senator Kamala Harris as his pick for vice president. Harris famously comes from a background in law enforcement as a former prosecutor who rose to the rank of state attorney general, a position she held from 2011 to 2017. Critics have dissected her record from that time with a focus on her office’s punitive response to truancy in public schools and stubbornness in cases of wrongful convictions. But over the course of her 11-month presidential run, and now again with her nomination as vice president, there has been another discussion happening in Indian Country about whether Harris will be an ally of tribal nations seeking the right to land that was legally guaranteed to them.

Depending on whom you listen to, Harris is either a politician who’s shown a tremendous amount of growth during her three-plus years as senator on the issues of tribal nations, or she’s a former attorney general who flagrantly blocked the pursuit of tribal sovereignty. The two characterizations are not mutually exclusive, but the question of what her nomination means for Indian Country demands that both of these truths, and her limited powers if elected as vice president, be appropriately weighted. That means not fawning over Harris when she sponsors a batch of progressive Native-focused legislation and not wholly condemning her for some truly harmful decisions she made in the past. There’s also cause to be relieved that she now won’t be tapped for U.S. attorney general.

While the Democrats certainly have been the more empathetic and outspoken party on Indian Country political issues, these matters often do not adhere to partisan lines due to their legal nature. The Obama administration endeavored to show how important tribal consultation is to establishing a healthy relationship with the 574 federally recognized tribal nations; it also reigned during the violent militarized police response from state and federal forces to the Standing Rock protests against the Dakota Access pipeline. Conservatives in Congress, like Representatives Tom Cole (Chickasaw) and Paul Cook and Senator Lisa Murkowski, have regularly championed issues of tribal communities. Last month, Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch, a Trump appointee, delivered the crucial swing vote and authored the opinion in the biggest tribal legal victory of modern times when he ruled that the United States was still bound to the treaty it signed in 1866 with the Muscogee (Creek) Nation.

Being a Democrat does not automatically win Biden and Harris the votes or confidence of Native peoples. The pair will have to prove that they have good policy plans in store as well as a blueprint for how they will set about reverting federal agencies to work for, not against, tribal nations.

As shown by the past three-and-a-half years under the Trump administration, the most defining decisions made by a president, as it relates to tribal nations, tend not to stem from executive orders but from whom they appoint to head the Department of the Interior, the Department of Justice, the Department of Health and Human Services, or DHHS, and, if they have the chance, whom they tap to fill a Supreme Court vacancy. Many of the issues facing Indian Country are predicated on how these departments read and respond to treaties and the subsequent land rights they define.

The DHHS oversees the chronically underfunded Indian Health Service, or IHS—underfunding that amounts to a treaty and trust violation. The Interior Department houses the Bureau of Indian Affairs, or BIA, which is often the main line of communication between the administration and tribal leaders and organizations. The Bureau of Land Management, also housed within the Interior, oversees the approval of oil and mining operations, decisions that often bump up against tribal lands. And the Department of Justice houses the FBI, which continues to have jurisdiction over major crimes committed on sovereign tribal lands.

The most glaring example of how these offices can have monumental effects on tribal nations came in late March, when BIA Director Darryl LaCounte (Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians) informed Mashpee Wampanoag Tribal Chairman Cedric Cromwell that the Mashpee reservation would be taken out of trust by the federal government, effectively disestablishing their claim to sovereign land.

The reasoning for the decision dated back to 2018 when the Trump administration’s Interior, citing the 2008 Supreme Court case Carcieri v. Salazar, issued a 28-page letter ruling that the department could not take the land into trust. This reversed a 2015 decision by the Obama administration that set aside 321 acres for the tribe. Trump’s opposition was also typically self-centered: Matt Schlapp, husband of Mercedes Schlapp, the White House’s former strategic communications director, was a lobbyist for a nearby Rhode Island casino that didn’t want the Mashpee to move forward with a gaming operation of their own, so he convinced Trump to spike two bills in Congress that sought to address both the Carcieri and Mashpee land issues. (The legislation has since passed the House and is stagnating in the Republican-held Senate.)

Removing the Schlapps from the equation, the Interior Department’s citation of the Carcieri ruling is relevant to this year’s Democratic ticket. The ruling established by the Supreme Court determined that the BIA can only move forward with the land-into-trust process if a tribe was “under federal jurisdiction” when the infamous Indian Reorganization Act was passed in 1934. It effectively created an unnecessary restriction for tribes that had been federally recognized in the 86 years since to legally claim the land wrested and stolen from them by the United States. It’s why the Mashpee have since tried to go through Congress to have their land taken into trust, and it was this same ruling that Harris, in her position as California’s attorney general, cited in the 2011 case Big Lagoon Rancheria v. California.

California is home to 109 federally recognized tribal nations and dozens more state-recognized tribes (meaning they are not recognized by the U.S. as sovereign nations). In Big Lagoon, Harris’s office cited Carcieri as it attempted to block the tribe’s establishment of a casino on an 11-acre plot of land that the Interior Department placed into trust for the tribe in 1994. Had the state of California won out, the case could have set a precedent that would have allowed the trust status of hundreds of tribes’ lands to be reviewed and reversed. When the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals unanimously ruled against Harris and California—saying that the state had waited too long to appeal the tribe’s claim to the land—Harris refused to comment publicly on the case as she pushed forward with a run for Senate. She appealed the court’s ruling three times and lost every time.

In her tenure as attorney general, Harris opposed 15 tribal land-into-trust applications. She also attempted to diminish the boundaries of the Colorado River Indian Tribes, submitting an amicus brief in 2014 that argued the tribe’s land could be used by a non-Native person because—despite what the federal government had held since 1969—the tribe’s western boundary moved with the Colorado River.

At the Frank LaMere Native American Presidential Forum held in Sioux Falls, Iowa, last August, Cheyenne River Sioux Tribal Chairman Harold Frazier confronted Harris over her history of fighting against tribal sovereignty and fee-to-trust applications. Her response was similar to her defenses of her harsh incarceration policies as San Francisco district attorney and California A.G.: “When I was attorney general, I had a number of responsibilities, including being lawyer for the governor. And it was in that capacity when the governor—I was the lawyer for the governor, and the governor made decisions about the fee-to-trust applications by California tribes. As the lawyer, as the law office for the governor, we had to file those letters. But that was never a reflection and has never been a reflection of my personal perspective, and when I have had the ability to independently act, not on behalf of a client, I think my history and my positions are very clear, which is that there has to be a restoration of tribal land.”

Contrary to this statement, Pechanga.net reported in 2014 that the then Governor Jerry Brown and senior aide Jacob Appelsmith “were unaware Harris’s office had sent at least 15 land/trust objection letters to the BIA since Brown took office in 2010.” Still, it’s true that as a senator, Harris has steadily developed into a friendly voice for Native issues. She has sponsored legislation like a Senate companion to the House’s Remove the Stain Act, which would revoke the Medals of Honor given to the soldiers who carried out the Wounded Knee Massacre. Last October, she pledged that as president, she would take half-a-million acres of land into trust for federally recognized tribes in addition to pushing for more tribes to assume autonomy over their local IHS operations. In the midst of the Department of Treasury delaying the distribution of federal pandemic relief funds to tribal nations, Harris lent her voice to the growing chorus of politicians criticizing the Trump administration’s response to the coronavirus in Native communities.

Biden has not been as proactive. He declined to participate in the aforementioned Native-focused presidential forum and was the last of all major Democratic presidential candidates to release an Indian Country policy plan. In the past four months, he’s taken steps to shore up this weak point in his campaign by hiring Native staffers, including a tribal engagement director, and pledging to make IHS funding mandatory. Biden also publicly supported the Mashpee this past spring. This is a start, but Biden and Harris still have a lot more work to do to convince Native nations. This is still a presidential candidate who, three weeks ago, had oil and gas groups saying they feel they can find “common ground” with his administration.

Despite Biden’s worn-out rhetoric, the goal cannot be to simply revert to the Obama era. To fully reckon with how damaging the Trump years have been for Indian Country, the next Democratic presidency must make tangible, meaningful progress. It has to build a future not just by listening to Native voices but by placing them in positions of power that lead to true self-autonomy, not further dependence on a federal government that too often has been apathetic to their needs when it matters most.

If Harris sincerely wants to be an ally in Indian Country, she needs to be a constant voice in Biden’s ear for the next three months. She must guide and advise him on who should head the crucial federal agencies that will make the decisions that have material effects on Native lives. Harris can push for the Interior and the DOJ to be helmed by people who have a proven track record of working with tribes, public servants who understand the contours of tribal sovereignty and treaty rights. Indian Country does not need someone who is merely sympathetic to its issues. It needs champions of its own with actual power. It needs a president who won’t just hold annual listening sessions but one who will go out of his way to ensure the administration is actively helping Native people. It also needs a vice president who is willing to take responsibility for her past mistakes and fight for a future White House that finally earns the right to be trusted by Indian Country.