Just as the physics of our atmosphere is no longer only the concern of atmospheric physicists, so has climate change become a dominating theme for writers of otherwise different concerns. From Jeff Vandermeer’s Annihilation to Nathaniel Rich’s Odds Against Tomorrow, the last decade has seen such a steep rise in sophisticated “cli-fi” that some literary publications now devote whole verticals to it. With such various and fertile imaginations at work on the same topic, whether in fiction or nonfiction, the challenge facing the environmental writer now is standing out from the crowd (not to mention the headlines).

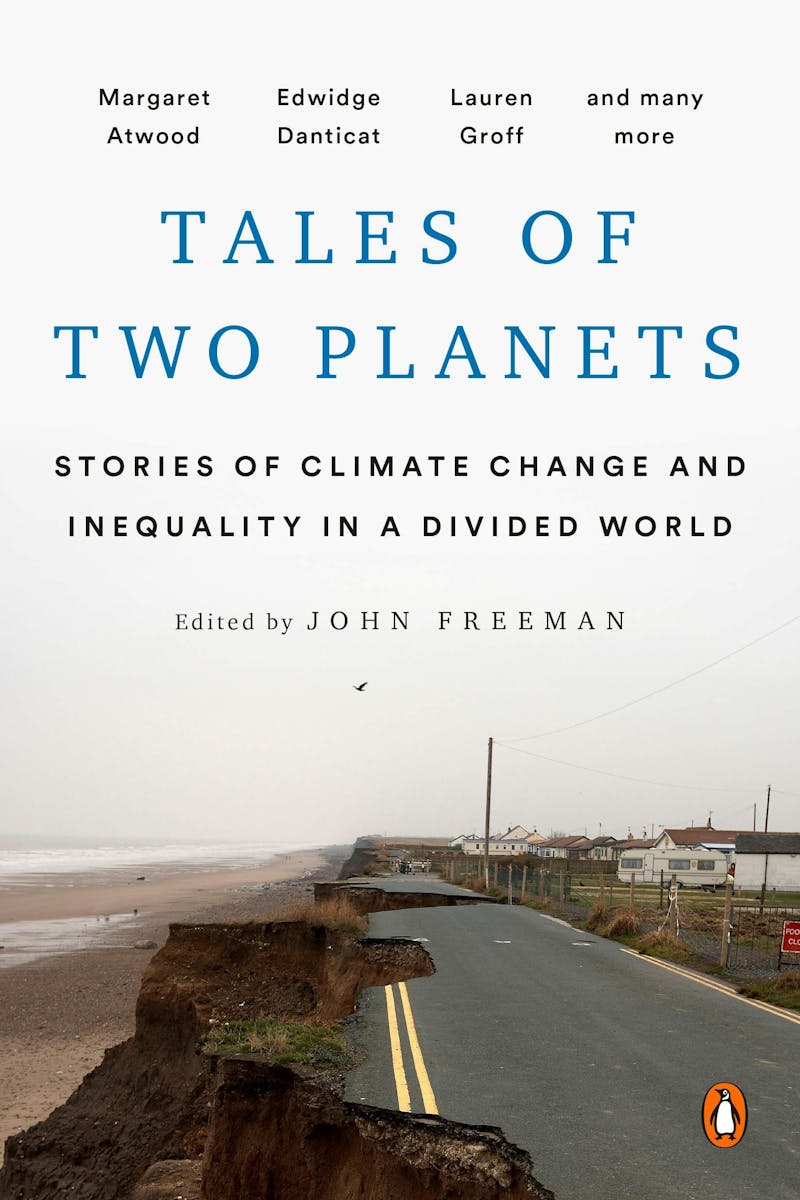

Two new books offer different strategies for capturing jaded readers’ interest. Ornithologist Jonathan C. Slaght’s Owls of the Eastern Ice: A Quest to Find and Save the World’s Largest Owl is a first-person account of slogging through the frost-bound Russian forest to locate and study the endangered Blakiston’s fish owl. In contrast to this drawn-out portrait of a single species, Tales of Two Planets is a mosaic-like compendium of short works compiled and introduced by John Freeman, former editor of Granta. The collection includes Edwidge Danticat writing about Haiti, a poem by Margaret Atwood, and a new Lauren Groff story about a mother immobilized by climate change-related depression, among 30-odd other views on ecological disaster across the world. Together, these two books offer contrasting, almost opposing, approaches to writing about the crisis and thinking about our relationship to the world.

Slaght describes a charismatic bird in peril from human influence. His race against the Primorye region’s melting ice and burgeoning logging industry acts as a universal symbol for the attempts to protect the vanishing species of our planet. The fish owl is special for its enormous size (wingspan: six feet) and ragged appearance; since its underwater prey can’t hear them coming, these birds haven’t evolved the sleek, soundless plumage of the owl species that hunt terrestrial creatures.

He teaches us how to find a fish owl in the woods (very patiently, by listening for their calls and then triangulating a location), grab it (by the legs, “in one fluid motion”), and appreciate their charm. “Like one of Jim Henson’s darker creations,” Slaght writes, one particularly endearing fish owl he meets is “a goblin bird with mottled brown feathers puffed out, back hunched, and ear tufts erect and menacing.” They’re also aggressive, as are some of Slaght’s Russian traveling companions, which gives Owls of the Eastern Ice the heroic flavor of A Boy’s Own Story.

Early on, for example, Slaght tells us about a man who lost a testicle to a fish owl and subsequently shot many in revenge: “They say he went out one night to take a dump in the woods ... and he apparently squatted right over a flightless young fish owl that had just left the nest.... The bird just grabbed and squeezed the closest bit of flesh, the lowest-hanging fruit, you might say.”

Slaght regularly peppers his book with such anecdotes, little doses of bro-humor in the Primorye style mixed with bird facts. When he and his crew bunk up with the odd forest-dwelling local, furthermore, Slaght gets invariably pulled into a masculinity contest with their host. “There are two reliable ways to get a Russian man to respect you,” he writes. The first is “to consume voluminous amounts of vodka” while “the other is to go toe-to-toe in a banya,” the Russian equivalent of a sauna. “I had long ago stopped trying to keep pace with Russian men and their drinking,” Slaght writes, “but in those days, I could steam with the best.”

Owls of the Eastern Ice is an undeniably compelling story, especially for a book about owls, but there’s something almost retrograde about this story of a hero chasing animals through the wilderness and glaring at Russian strangers across the banya steam clouds. One of the key ideas of the school of “ecocriticism”—an umbrella term for the study of the relation between literature and the environment—is that “man” and “nature” form a false dichotomy. If we want to exist responsibly within the earth’s delicate ecology, Timothy Morton argues in Ecology Without Nature, we have to resist the binary that categorizes the human being as somehow separate and distinct from the rest of the world, which we tend to lump into the messy and ill-defined category of “nature.”

By telling his epic tale of man and owl, Slaght ends up inadvertently reinforcing some of the assumptions that ecocriticism most abhors. In his introduction to the 1995 book Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place, William Cronon wrote that “wilderness” is itself a toxic concept. “Far from being the one place on earth that stands apart from humanity,” Cronon writes, wilderness “is quite profoundly a human creation.” As we gaze into wilderness’s mirror, “we too easily imagine that what we behold is Nature when in fact we see the reflection of our own unexamined longings and desires.”

Tales of Two Planets is full of such varied writing that there’s no opportunity for cliché to take hold. Some surprising connections flow through its different parts, however: In Bangkok and in Buenos Aires, for example, the beauty of polluted sunsets is remarked upon. “Champagneworthy sunsets are yours every evening,” writes Pitchaya Sudbanthad.

In his essay “Song of the Fireflies,” Gaël Faye writes about the forested hill his father once purchased in northwestern Burundi. As a child, Faye would catch fireflies in those woods and tell his father he’d caught a star. Now the glowing insects are gone, exterminated by development. What could become a too-simple discussion of extinction changes, in Faye’s hands, into something that links him to Italy. He quotes a 1975 article by Pier Paolo Pasolini on the same phenomenon occurring in his own region: “In the early sixties, due to air pollution and, above all, in the countryside, due to water pollution ... the fireflies began to disappear. ... Within a few years, there were no fireflies left.” The absence becomes Faye’s subject—a universal absence shared by all the places species once were but now are not—rather than the firefly itself.

Elsewhere in the collection, several writers refer to underground systems in major cities as physically obscene. Freeman describes Paris “lifting her skirts” to allow him into the catacombs while Lina Mounzer’s essay about Beirut’s failing plumbing calls sewage the “underground twin” flowing beneath every city: The sewer is the city’s “dark heart; its churning guts.” It’s a metaphor for urban systems that drift between the sexual and the scatological, insisting we focus on that which town planning conceals from our view—just as Cronon wanted us to look at the parts of ourselves that words like “wilderness” gloss over.

In his introduction, Freeman agonizes a little over the point of all these words. “Should we be elegizing?” he asks, of whittled-down ocean reefs and our earth’s other many losses. “How do we honestly remember what was so clearly never valued?” The sheer variety of approaches in the book reflect something of that frenzied feeling; the collection takes you on a joltingly rapid journey across the world (India, Bangladesh, Hawaii, Iceland). But that eclecticism is also what prevents A Tale of Two Planets from sinking in the kind of ideological mud that bogs down Owls of the Eastern Ice, a reminder that excellent environmental writing can come from literally anywhere—not just the frozen tundras of macho adventure stories.