A quarter of the way through Héctor Tobar’s novel, his young, blond protagonist stands on the edge of National Highway Number 9 in Chile, thumb pointed south in hopes of hitching a ride. Drivers speed past, giving him puzzled looks, and only when a taxi stops does Joe Sanderson find out that there is nothing south of Punta Arenas. “This is the last town, the last place in Chile where people live,” the driver says. Nevertheless, the man agrees to take him to the end of the road, site of an old colonial fort and a “very, very cold” place. The road ends, Joe proceeds by foot toward Fuerte Bulnes, and the paragraph soars in the style characteristic of the book, jeweled with lyricism but freighted with history:

Climbing the slope on which the fort resided, he saw the soapy blue current of the famous straits sought out by European mariners. Calm ocean water, sheltered from bigger, meaner seas. Magellan and his crew navigated through this channel, their Portuguese sails catching the wind, steel helmets rusting in the misty air, the captain and his sailors thinking: Is this the way, have we found it? Asia and spices and riches! Magellan’s eyes upon the way forward, to Japan and then Africa and home to Lisbon. And now my eyes on this same body of water, lonesome waves. From Urbana to here.

Tobar’s hero is an ingenue, perched in the full glory of his American innocence on the edge of a world shaped irrevocably by successive waves of domination. Raised in Middle America by loving middle-class parents—his father is an entomologist, his mother a bank official—in the booming middle decades of the twentieth century, Joe is driven by aspirations to be a writer. Bored in college, restless, he decides to hitchhike across the world in a bid to find suitable material for his great American novel.

Joe’s journey is, for the first part of Tobar’s book, a freewheeling, blurry picaresque, borders and years dissolving before the young man. Possessing no more than a spirit of adventure and unselfconscious imperial privilege, he sweeps through countries and continents. Across Central and South America, to North Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia he goes, finding hospitality among elites and underclass alike, welcomed by both policemen and fellow Western bums. His modes of transportation include trucks, buses, VW vans, trains, cruise ships, freighters, planes, helicopters, and foot.

The trips are funded by occasional returns home to the Midwest, where Joe paints flagpoles flying the Stars and Stripes. He is, after all, a patriot, someone who has done basic military training and supported the presidential bid of Richard Nixon. When he is back on the road and cash runs short, he has his mother or brother wire him money to the U.S. Embassy next on his itinerary. Otherwise, he shares the resources of women he meets and seduces on the way. Occasional excerpts from Joe’s letters home to his mother capture both his own charm and that of the world as he perceives it, and it is easy to marvel at the astonishing lists that make up chapter headings: “Vientiane, Laos. Bali, Indonesia. Djibouti, Afars and Issas. Addis Ababa. Kigali, Rwanda. Stanleyville, Congo. Johannesburg. Lagos. Uyo, Biafra.”

It is around this time, however, that Joe’s vision begins to darken. In Saigon, he sees teenage Vietcong guerrillas summarily executed after a skirmish. In Laos, as Buddhist monks in orange robes walk the dirt and asphalt streets of the capital, B-52 bombers rain free-world benediction upon the forests. In Biafra, he encounters the devastation of famine up close. His letters home attempt to give voice to the eerie details extracted from these journeys, the “Yankee bombers moving back and forth overhead from runs into Vietnam and the Ho Chi Minh Trail,” their target population consisting of “bare-breasted women, kids with malaria, workers making 50c per day.”

The change in focus suggests an internal shift: The places he is traveling through are no longer a backdrop. While Joe is collecting material for his unwritten novel and attempting to find a suitable voice, he is also engaged in a process that Tobar considers far more important, especially in our bewildering present moment, when writing often seems to be entirely about the privilege of self-discovery. Joe is beginning to discover not just the relationship between the world and his aesthetic impulses, but also the bloody, vital interplay between writing, politics, and the world, with the ensuing dialectic of failure and hope that forms the subject of Tobar’s own novel.

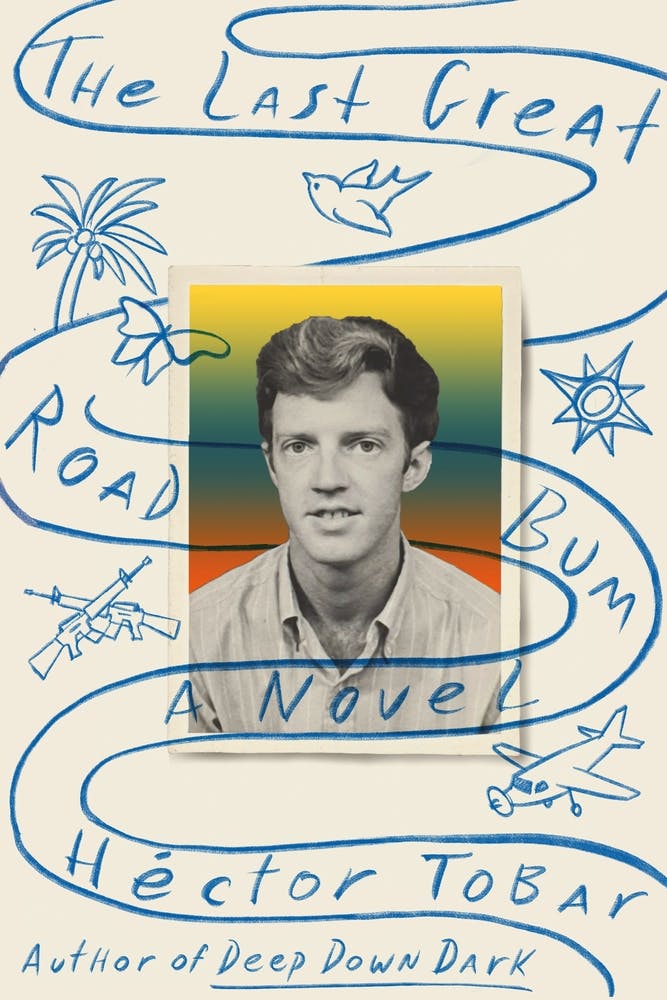

Joe Sanderson was a real person. Dropping out of college and rejecting many of the comforts of his American birthright, he was—as Tobar informs us in a preface—a vagabond drawn to those places once called the Third World, tracts of the globe trying to break the shackles imposed upon them from Magellan onward. Traveling this decolonized and decolonizing world for 20 years, Sanderson eventually died in El Salvador, leaving behind a journal that ended up in Tobar’s hands. Sanderson’s mother, Virginia Colman, preserved and cataloged the letters he had sent her from around the world, while his brother Steve assembled an archive that included boxes of unpublished novels. This was the varied matter, fictional and nonfictional, that Tobar has drawn on in his novelistic rendering of Sanderson’s life.

It’s not difficult to imagine why such material might have attracted Tobar. Based in California and the child of immigrants from Guatemala, Tobar has in his writing encompassed fiction and nonfiction as well as the United States and Central America. His brilliant first novel, The Tattooed Soldier (1998), brings together Antonio, a refugee in Los Angeles suddenly rendered homeless, with the man who murdered his wife, Elena, and two-year-old child in Guatemala. Tobar’s second novel, The Barbarian Nurseries (2011), is set in the aftermath of the financial crash of 2008 and centers around Araceli, a Mexican woman working as a maid for a well-to-do California family. His nonfiction, meanwhile, includes Translation Nation (2005), a reported account of the Latino population living in the United States, and Deep Down Dark (2014), which captures the story of 33 men trapped in a copper-gold mine in Chile for over two months.

The continuity between these books is obvious, from the interest in marginal lives—migrants, refugees, the working class—to the exploration of violent historical forces that have set adrift so many peoples and cultures within Central America and the United States. Stylistically, too, there is a coherence. In the novels, especially, one encounters a noirish collision between character and plot, with ballast provided by the writer’s urge to describe the reality. As Araceli takes the children in her care to Los Angeles in The Barbarian Nurseries, Tobar writes:

Their bus headed eastward, deeper into the modern industrial heart of the metropolis, over the north-south thoroughfares and railroad tracks that carried cargo and commerce, into districts of barbed wire and sidewalks blooming with fist-sized weeds, past stainless-steel salt-water tanks excreting briny crystals, past industrial parking lots with shrubbery baked amber by drought and neglect, past storage lots filled with stacked PVC pipes, past stunted tree saplings and buildings marked CHOY’S IMPORT and VERNON GRAPHIC SERVICES and COMAK TRADING, and through one intersection where a single tractor-trailer loomed and groaned and waited.

From the days of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler to contemporary crime shows, this has always been noir’s remit, the coupling of infrastructure and ruin. Yet, as The Tattooed Soldier makes clear when it shifts from Los Angeles to Guatemala, with its student revolutionaries, oppressed indigenous peasants, and right-wing death squads, Tobar draws from literary traditions of the decolonizing world as well. The deep, lingering gaze over material details, we learn, is also a scrutiny of modernity as handed down by colonialism, a signposting of history’s violent relationship to individuals and to groups.

The romance between Antonio and Elena begins, for instance, with him giving her a bilingual Spanish-Quiché dictionary. It is an attempt on their part to resurrect the indigenous life pushed into the margins, an uprising that intersects with feminism and Marxism, the utopian dream of it all captured by graffiti on university walls that reads, “a zoo for the generals, power for the people.” Yet when they flee the capital with its abductions and assassinations, what they see outside the bus window is the “towns with Quiché Indian names, Hispanicized centuries ago.” A litany of place names reminiscent of Roberto Bolaño follows—“Chimaltenango, Tecpán, Chichicastenango”—the sounds an exhortation to remember what has been suppressed, what exists only as half-visible residue.

Tobar’s latest novel builds on these interests, as Joe’s vagabond spirit opens up the clash between empire and its subjects beyond the United States and Central America. Everywhere Joe travels, the world is unraveling, and underneath the freedom that Joe’s race and nationality confer on him are those paying the price for that freedom. It is to the credit of the historical persona of Joe Sanderson that he did not remain oblivious to this one-way trade, but it isn’t immediately obvious why Tobar chose fictional form to capture his journey into greater involvement.

After all, Tobar’s early novels, for all their brilliance, remain in the shadow of his nonfiction books’ commercial success. Deep Down Dark, a bestseller, received unanimous acclaim from mainstream reviewers as well as the imprimatur of a mediocre Hollywood adaptation fronted by Antonio Banderas. There is also the fact that The Last Great Road Bum does not initially offer much in the way of significant novelistic pleasures—interiority, nuance, shifts in pacing. The new novel lacks the striving for self-awareness that Antonio, Elena, and Araceli display in the early fiction. There are extensive descriptions of places, but few scenes and little dialogue. Other characters—especially the women Joe is involved with—drift by as vignettes, although Tobar occasionally deploys free indirect discourse to jump into multiple points of view, offering brief glimpses of emotions and thoughts, or even intellectual complexity one suspects would not have come naturally to Sanderson.

The accelerating narrative is impeded only occasionally by the footnotes where Joe, speaking from the great beyond, offers his thoughts on Tobar’s fictionalization of his life. These footnotes aren’t always convincing as a device. They seem to replicate the goofy persona Joe affects in his letters home, which Tobar excerpts occasionally in the main narrative. Masculine, white, North American, always ready with a joke or a moniker that reduces the unknown world to familiar cultural markers—these are traits likely to come across as especially grating after close to a century of U.S. hegemony. But Joe’s voice sells himself short as much as it reduces others, because beneath the sunshine, there is complexity.

One senses this in Joe’s loneliness and in his brief affairs, in his inability to settle down during his short stints at home, and in the growing sense of woundedness in him as he takes in the state of the world. And at the heart of his story is the conjoined failure of art and revolution that perhaps gives the book its greatest emotional charge as well as a basis for Tobar’s decision to pursue it as a novel rather than as nonfiction. Within this novel, one that Tobar worked on for over a decade, is Joe the failed novelist, spending his entire adult life producing fiction that would never be published in his lifetime.

During his trips back home, when Joe is not painting flagpoles, he is busy typing out his copious travel notes into manuscript form. Taking his observations on Biafra, he writes a novel called The Children’s Song, with an unnamed protagonist in the second person. The manuscript comes back, rejected, producing a moment of incredible vulnerability in Joe’s story. “He had circled the world, gone off and seen wars and the aftermath of wars in Korea, Vietnam, Yemen, Congo and Biafra, and he had watched children die in his arms—and none of it added up to a book anyone would publish.” One could easily see this as privilege. After all, what is his pain compared to the pain of those in Asia and Africa? And yet he seems to be stumbling upon the larger truth that suffering counts for very little precisely in those places structured to inflict misery at will upon the world.

He writes another novel, The Cocaine Chronicles, based this time on his exploits as an amateur pilot and involvement with a gringo cocaine dealer in Bolivia. Again, he falls short as a novelist. If Joe’s life is like that of a protagonist in a Hemingway novel, his writing has nothing of Hemingway’s hypnotic tautness. It is energetic but shapeless, filled with ellipses and monologues in a disregard for form and style that seems to be another aspect of his freewheeling American inheritance. Even his father declares, after reading 20 pages of The Cocaine Chronicles, “Son, I think some editing might help here.”

The failure of Joe’s art intersects, in the final section of Tobar’s novel, with the Salvadoran revolution condemned to a brutal defeat, one reverberating decades later in the confusion of undocumented migrants detained and vilified along Trump’s border wall. It is part of a larger story about the destruction of Central America, from genocidal war in the 1980s to the subsequent, ongoing gang violence, poverty, forced migration, sexual exploitation, and incarceration by the hegemon responsible for so much of the suffering, and one that has been amply documented by a number of writers.

The American poet Carolyn Forché’s recent memoir, What You Have Heard Is True, eloquently describes her involvement in recording the savagery of the war in El Salvador. It was an experience that birthed her idea of the “poetry of witness,” its most singular example being the poem in which a Salvadoran colonel, having invited the poet home to dinner, tosses a bag of human ears on to the table. Another forthcoming memoir, Unforgetting, by the California-based writer Roberto Lovato, details a youth that involved witnessing gang warfare in San Francisco and traveling to the El Salvador of his parents to become a guerrilla. The journalism of Salvadoran Óscar Martinez, meanwhile, daringly and painstakingly captures the long, ongoing aftermath of the war in Central America, from the crammed prisons to the overcrowded trains and buses on which children and adults try to make their way up north.

“This book isn’t about Martians,” Martinez pleads in the preface to his recent work, A History of Violence. Yet all these books about Central America and its peoples might as well be about Martians. The fact that the best-known contribution of contemporary U.S. publishing to forced migration, borders, and gang violence is American Dirt, with its barbed-wire theme book party and bestseller status on Amazon, reveals the deep sickness of a system that, having destroyed entire nations, celebrates its self-serving accounts of such destruction.

Culture is often just another weapon to go with military training in U.S. bases. Against such deception, Tobar’s flawed and human hero stands out with surprising clarity. Middle-aged and alien among the peasants, workers, and students fighting a guerrilla war against the Salvadoran army and its American specialist advisers, temperamentally ill-suited to the discipline demanded by an armed uprising, Joe carries on. He is there to observe and to record when his squad arrives at El Mozote after the Atlacatl Battalion has massacred over 800 civilians in the village, stumbling over ammunition manufactured in Missouri and sifting through the rotting, half-burnt corpses of adults and children.

The experience completes a transformation already in the making in Vietnam and Biafra. His skills as a marksman, his brief training with the U.S. military, his medical knowledge, and his white American voice—everything is deployed in service of the revolution as Joe stumbles along with the Salvadoran guerrillas from mountains to sea and back. And it is in this final part of the book, where the failed writer collaborates in what will turn out to be, in many ways, a failed insurrection, that Tobar allows Joe his own voice directly on to the page. An excerpt from the pages of his journal is presented, stand-alone, complete with heading and byline. A memorial and a tribute on Tobar’s part, it ushers into print an unpublished writer after half a century of silence. In that is a riposte to the idea that either Joe’s life or death might be meaningless, with the accompanying assertion that neither art nor justice is the burden of one person alone.