In early May, after eight weeks in quarantine, Italy embarked on fase 2 of its coronavirus response and, step by step, relaxed its restrictions. From that day, families were once again allowed to meet one another, and restaurants could reopen, if only for takeout. Most shops, bars, and museums reopened in mid-May, while schools and nurseries remained closed. Physical distancing, though, has remained in effect.

A week earlier, on Friday, April 24, the Commune of Milan announced its vision of urban life after lockdown. In Milan—the cultural and economic powerhouse of the country—city planners envisage a radical reconfiguration of urban space. Pre-corona, two million people were using public transportation in the city every day. Post-corona, that number will need to go down to half a million to keep people a safe distance apart. Additional cycling lanes will be rolled out, and the speed limit for cars will be lowered to 30 kilometers per hour across the city. That is a massive reduction in the flow of people through the arteries of a city. Where will they go and what will they do there? The plan was that instead of taking the subway to work, visiting La Scala, or patronizing one of the glitzy shops in the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, the grand 1870s shopping arcade opposite the Milan Cathedral, most people will work at home, go to local shops, and listen to street musicians and chamber quartets in their local square.

Six hundred miles north of Milan, in Wolfsburg, Germany, on the following Monday, at 6:30 in the morning, 8,000 workers made their way through the gates of the Volkswagen plant and resumed exactly where they had stopped five weeks earlier: making VW Golfs. By the end of May, half the workforce was back at the factory.

The contrasting scenes in Milan and Wolfsburg reflect the contradictions at the heart of consumer capitalism in the age of the coronavirus. The two strategies are clearly incompatible. If people do most of their work, shopping, and leisure within a 15-minute walk of their home, they will probably not buy a new car anytime soon. Milan looks toward pedestrianization, rinaturalizzazione, diffusion, and flexibility. Yet VW’s faith in future demand may not be completely misplaced. With airports shut, public transportation a potential source of contagion, and beaches closed or access rationed, people may very well want to buy more private cars to visit friends and family or to escape safely to the countryside.

What will the future of consumption look like? Will there even be a future? Three scenarios are making the rounds. For optimists, the current crisis is like a momentary cut in a film. There will be a short intermission and a fair bit of pain, but (with the help of central banks and generous stimulus outlays) the celluloid will be taped back together again, and then we will resume watching the story of our lives where we left off. Unlike other crises—say, an earthquake or a war—the coronavirus did not destroy machinery and infrastructure. All of Germany talks of the need to hochfahren or “boot up” the economy, tourism, and much else, as if we are dealing with a computer or a machine that can simply be switched back on. The Bank of England also assumes a “rebound.” The 2020 lockdown will destroy 14 percent of gross domestic product, it says, but don’t be scared: In 2021, we will be back and grow 15 percent! As one friend put it, “People have short memories. Soon they will all book their next cruise.” Michael O’Leary, the chief executive of Ryanair, said in early June that British quarantine rules were “rubbish,” and that the budget airline would continue to operate flights as scheduled regardless.

Then there are the doomsayers. To them, the world was already on a cliff edge in 2019. Globalization had been in retreat, productivity stagnant, and spending squeezed. The lessons of the 2008 financial crisis had not been learned. The coronavirus, in this view, is now pushing us over the edge, into a downward spiral of recession, mass unemployment, collapsing demand, poverty, conflict, and war.

Finally, there are the alternative optimists. To them, the crisis will pull down consumer capitalism but, luckily, in its place bring forth a nirvana of greater self-sufficiency, environmental stewardship, and social justice. Finally, the air is clean and the birds are singing. Lockdown, in this view, is shaking people out of their materialist slumber, exposing all the “false needs” they had been brainwashed into, and teaching them to focus on their “real” needs instead: health, family and friendship, and baking bread. This view, it is worth noting, is not limited to environmentalists, critics of neoliberalism, and disciples of simple living. It is shared by some retail analysts. “If I sat here for the last three months,” one British consultant said, “and I haven’t bought a new pair of shoes or a handbag, maybe it wasn’t as important as I thought it was?”

What is clear is that we are dealing with an unprecedented crisis. At the time of writing, almost all rich societies have had a taste of lockdown. In addition to the initial countermeasures taken to slow the spread of contagion, and flatten the pandemic’s curve of lethal exposure, there will be a second and, perhaps, third wave of the virus to worry about. People have flocked to parks and beaches and joined protest marches. Still, all countries that have come out of lockdown continue to have various restrictions in place, from limiting numbers in bars and entertainment venues to the prohibition of group sport and leisure. Scientists have warned that some physical distancing measures may need to remain in effect until 2022. Even Sweden and South Korea, which allowed shops and restaurants to stay open in spring, have not been able to escape commercial meltdown. Fewer people eat out in South Korea today than last year, and a sudden rise in the number of infections prompted a shutdown of bars in early May. Shopping malls in Stockholm are half empty; H&M sales fell by half in Denmark and Finland, but even in Sweden, without a lockdown, they dropped by a third.

Wherever we look, figures and forecasts are getting more dire by the day. In the first quarter of 2020, the U.S. economy shrank by 4.8 percent, and 30 million filed for unemployment benefits between mid-March and early May. Spain is suffering the biggest recession since the Civil War (1936–39). Germany and Switzerland predict a 6 to 7 percent drop in GDP for the year. When I started this article in the middle of April, British forecasts were for a 6 percent drop in GDP. In early May, the Bank of England published its scenario that put it at 14 percent. This would be the worst recession the nation of shopkeepers has suffered for three centuries; by comparison, in the 2009 financial crisis, the British economy contracted by 4 percent. In Britain, a quarter of the workforce has been laid off; one million people applied for social benefits (Universal Credit) in the last two weeks of March alone. American and British estimates predict that consumption will drop by 15 percent this year, and some analysts think even that might be optimistic.

What makes the coronavirus so disruptive is not so much that it will take a few thousand dollars out of the pocket of the average customer this year; rather, it’s shaking the foundations on which modern consumer culture has been built over the last 500 years. The imperial trade in exotic goods, the lure of novelty and fashion, the expansion of comfort and convenience, and our accumulation and ever-faster replacement of possessions have been the result of a dynamic exchange between the local and global, the home and the city, public and private. Bright, colorful cotton from India; porcelain cups from China; sugar, coffee, and cocoa from the Caribbean and Latin America; curtains and carpets, the tea party and coffeehouses, urban arcades, pleasure gardens, cinemas, and department stores—all of these depended on the joint movement of goods, people, and tastes. The Bon Marché, Selfridges, and other department stores around 1900 were not entirely revolutionary, but one practice they introduced proved critical to the later consolidation of a culture of consumption: the simple act of letting customers touch the merchandise. Contemporaries compared them to ocean liners—and that is, of course, precisely why some have remained closed and, in several cases, will stay closed forever.

The virus has effectively stopped several pistons of consumer economy at once. Tourism and mobility, restaurants and retail, live entertainment and sports: Each of these is a big sector in its own right, but together they are enormous. In the United States, 6 percent of total consumer spending is on restaurants and hotels alone, and another 4 percent goes to recreation. Italy, Austria, and Spain each make about 14 percent of their GDP from tourism, Greece as much as 20 percent. Retail experts forecast that 20,600 British stores (with a quarter of a million jobs) will have closed their doors by Christmas. Germany has some 70,000 hotels and restaurants. How many of these will survive the crisis? In Germany, some theaters are reopening, but with only half the seats. Sporting events are gradually resuming, but behind closed doors. Broadway is not expected to reopen until 2021.

What makes the virus so damaging is its synchronized effect on activities that mutually depend on mobility and proximity. Fewer tourists and business travelers translate into fewer hotel and restaurant guests and fewer visitors to shops, special exhibitions, concert halls, and musicals. Take the cruise, for example. Cruises took off 30 years ago. Last year, 30 million passengers sailed the seas. They generated $68 billion in direct expenditure where they docked—spending on excursions, trinkets, and shopping, along with all the food and drink and supplies bought for the ships. The Mediterranean and Baltic routes are now almost as popular as the Caribbean. Half a million passengers embarked last year in the Finnish capital of Helsinki, which has just over one million inhabitants. The MSC Meraviglia alone carries 4,500 passengers to Norway. You can argue whether the 15-deck, 315-meter–long behemoth deserves its name (“Wonder”), and cruises and airplanes carrying package tourists are big polluters. Still, the spectacular new music halls, arts festivals, and restaurants that have regenerated many Nordic cities are inconceivable without them.

When we think about the future of demand, though, we need to ask about its quality as well as quantity. What is all the demand made up of that we are so worried about? And how is life during and after lockdown changing the activities that result in demand? These may appear straightforward questions, but they are ones that economists and policymakers have been finding very hard to get their heads around. Many simply assume that we will “rebound” and gradually resume our lives more or less where we stopped before lockdown—as if the experience of isolation and ongoing distancing will not change how we consume (and what we “demand”) at all. At most, they assume that it will take a few months for people to flock back to restaurants. This is an extremely narrow view of consumers and how they lead their daily lives: All eyes are on the money in people’s pockets and how much makes it into the cash register. But consumption is not simply a reflection of how much money there is to spend. We need to know why people turn to certain goods and services in the first place. And disruption changes that.

The consumer is more than a customer. Home economists such as Hazel Kyrk a century ago understood this very well, but there is no harm in repeating it. Spending is just one element in the chain of consumption that connects motives, desires, and acquisition to our habits and what we do with the stuff we’ve got.

When it comes to motives, many commentators point their finger instinctively at status-seeking. This is an explanation that reaches back to Thorstein Veblen’s critique of the superrich and their “conspicuous consumption” in the United States during the Gilded Age, through Jean-Jacques Rousseau all the way to the ancients. We can all probably think of examples of such behavior—the designer handbag, the luxury watch, or any number of tech gadgets.

Showing off, of course, does exist, but it is only one of the drivers behind consumption. Possessions are also key for our “material self,” to use the concept coined by William James, the father of psychology. Our clothes, our car or bicycles, our phone, heirlooms, and souvenirs: These are not just the misguided expression of “false needs” but make us who we are. Consuming also functions as a cultural grammar we use to communicate social norms and values. Think of the family meal or the emerging custom of the virtual house party. Finally, a good deal of consumption is about “doing” stuff. It is about accomplishing a task and requires materials, competence, and infrastructures—in the case of baking: flour and yeast (if you can find them), kneading technique, an oven or a bread maker, recipes obtained via Google, a kitchen, gas and electricity, or at least charcoal.

The pillar of consumer culture hardest hit by lockdown and distancing is the city, the epitome of both proximity and mobility. Cities have been the beating heart of modern consumer culture, and their shops, restaurants, and cultural spaces are the crucial arteries for the circulation of goods and experiences. David Hume, the eighteenth-century Scottish philosopher, saw that the pursuit of goods, sociability, and urbanization was symbiotic. The pursuit of “modest” luxuries, like porcelain cups or a fashionable dress, he wrote in 1752, made people more demanding and creative. In turn, “the more refined arts advance, the more sociable men become.” Their curiosity and taste will make them flock into cities to share their “knowledge … [and] to show their taste in conversation or living, in clothes or furniture.” They will form clubs and societies and seek to contribute to one another’s pleasure and entertainment. “Solitude,” or living “in a distant manner,” Hume wrote, was “peculiar to ignorant and barbarous nations.”

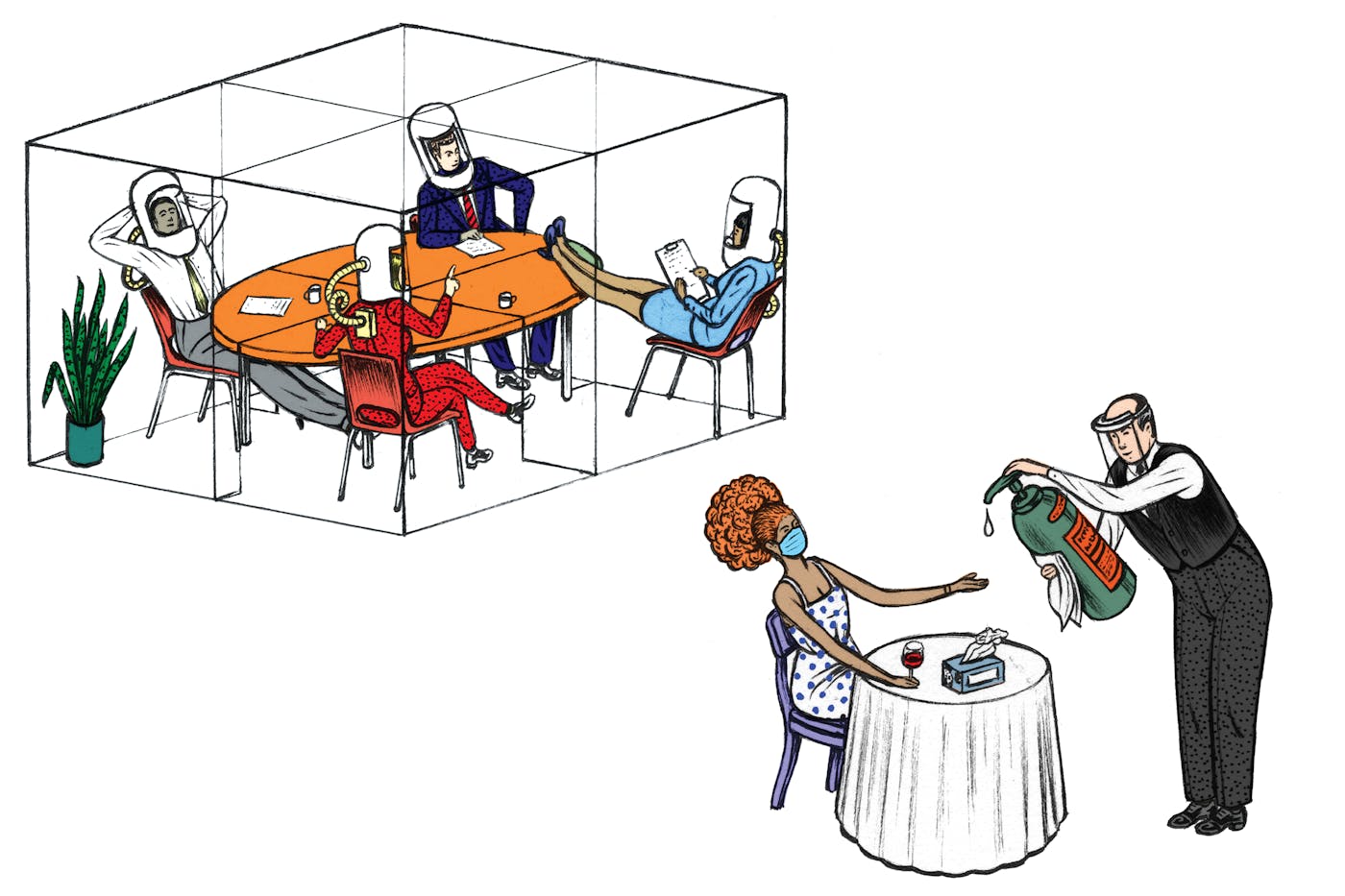

By shutting down cities, the coronavirus has switched off the urban pleasure economy. Take the widespread activities of going clubbing, to the theater, or to a sports match. These large gatherings are typically not isolated events but are often combined with dinner beforehand and a drink and conversation afterward. Restaurants have reopened in some countries—in Austria, a family can sit together at a table; in Italy, diners can eat behind plastic screens—but the chain between activities remains broken. What makes it so hard for restaurants, as for other sectors we will encounter, is that the lockdown is merely amplifying preexisting trends. High rents and a squeeze on consumer spending have left restaurants more vulnerable than ever. In Britain, 1,000 went bust in 2017 alone.

In this sense, the great coronavirus disruption turns out to be a great acceleration. Yes, from Vilnius to Manhattan, there are plans to help out restaurants in the next few months by opening up streets and public spaces to alfresco dining at a distance. But how this will work in November or February, or in more inclement places like Dublin or Oslo, is a big question, even if we pile up blankets or turn on environmentally unsustainable outdoor heaters.

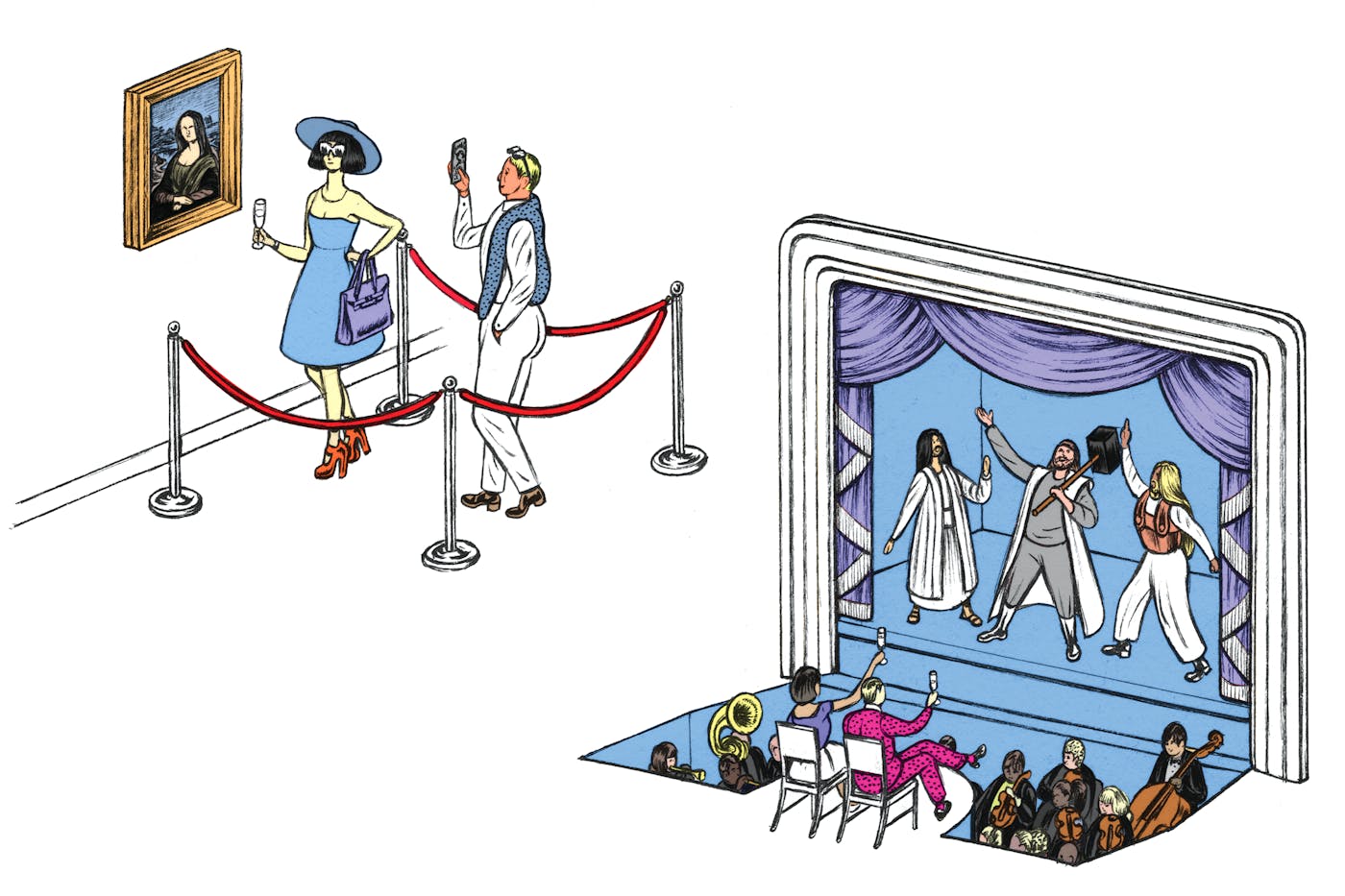

Concert halls, clubs, and sport stadiums face an even bigger struggle—museums are, relatively speaking, in an easier position, and Chinese, German, and Italian museums have already reopened with timed passes. Even there, however, capacity is radically reduced; the Archaeological Museum in Milan allows only 15 visitors every half-hour. Chinese museums cap their numbers at 50 percent and require health certificates. Cultural venues do not have a simple takeaway option, although it might be nice to fantasize about bringing a Turner or a Sargent home with you for a while. Digital online galas, ghost football games, and Zoom dance parties are not quite the same as the real article; hence the many voucher plans they’ve cobbled together to sell future tickets.

In the 1970s, the economist Staffan Linder predicted that the rise of real wages would make people shift from time-intensive leisure activities (such as learning how to play a musical instrument) to gadgets that offered instant satisfaction. Reality turned out differently. Yes, people have bought more electronic toys, but more have also been singing in choirs, learning the violin, or joining writing classes than ever before.

Lockdown and physical distancing cuts through the umbilical cord between “live” and “reproduced” forms of cultural consumption. What will be the consequences? On the one hand, we may witness some democratizing effects. If operas and symphonies will now mainly be streamed online, they will (like yoga classes) be much cheaper to join. On the other hand, since going to the opera remains a source of distinction, elites are likely to try to preserve their status through alternative, more intimate, and safer formats, such as private performances for special and screened guests only, as is already happening among the very rich. In other words, we are in danger of ending up with a two-class system of culture consumption: digital galas, “drive-in” live opera, and digital docenting for the many; the real “live” thing for the few.

Instead of “drive-in,” it might be more sensible to promote “drive-out” and reverse the logic of mobility: Bring culture to the people where they live, obviously at a distance. If the Soviets were able to do it, why shouldn’t we? In fact, the annals of consumer culture are full of suggestive examples. We’ve just forgotten most of them. What else are the fair and the circus? You did not fly to distant lands to see a tiger; the tiger came to you. Early cinema was traveling entertainment and introduced audiences to the moving image at fairs, in church halls, and swimming baths. The library van, traveling musicians and acrobats, the local bandstand—these could all be revived and adapted to our times. Most countries still subsidize cultural institutions on an appreciable scale, and those institutions will fight hard to keep their public funding streams. In the future, these could be tied to more diffused and localized forms of consumption.

Tourism, to take but one high-consumption pastime, is caught in a perfect storm of mobility and proximity. Party destinations like Ibiza and Ischgl (its Austrian cousin in the snow, and one early hot spot of coronavirus infection) will need to rethink their identity radically. In late April, the Balearic Tourism Minister Iago Negueruela suggested the islands may still reopen to visitors later in the summer—but at a reduced capacity of 25 percent. Party resorts and beach clubs will face distancing rules. Starting in mid-June, Austria reopened its lakes and mountains to tourists from abroad, but excluded Britons, Swedes, and others from countries where infection rates remain high. Most countries have quarantine restrictions for travelers from a number of countries.

Where will the millions of tourists go who no longer will be able to fly to Ibiza or Ischgl? In Germany, “save our summer” is almost a national anthem and comes right after the call to “reboot the economy.” In 1948 and 1949, the famous Berlin airlift brought food and coal to people cut off in the Western zone of the city. Now, there is talk of a tourist-themed airlift—one that would fly Germans to their spot in the sun; the German government has negotiated a safe tourism “corridor” with Greece and Croatia. This is how mobile affluence has changed mindsets.

If mobility becomes more costly, this will probably favor single, longer holidays rather than hopping for a few days to Barcelona, Florida, or New York. Hotels will start to compete with one another over safe spaces and hygiene standards. In Madrid, one luxury hotel is considering a virus-testing station on the outside and more individualized service on the inside, including a special safe route to the rooftop. To meet distance rules, however, it will need to cut capacity in its bar and restaurant by a third and a half, respectively. Airbnb struggles, because it can only incentivize individual “hosts” to offer higher hygiene standards, rather than enforce them. In China, Airbnb bookings started to recover in April, but only partly. Shanghai tourist spots capped normal visitor numbers at 30 percent capacity.

This may look like environmental progress, but that is not a given. Consuming at a distance hits all forms of sharing alike, public and for-profit, sustainable and unsustainable. In Milan, bike and scooter sharing fell by 84 percent in April. True, in Beijing, the number of shared bike rides since the end of lockdown has climbed back to 63 percent of its earlier usage. A regularly disinfected bike is still better than public transportation. But if you have your own car, that’s a far safer option; according to one survey, twice as many Chinese people now use their private car than pre-corona.

So far, one site of serious socioeconomic friction in the crisis has been over the second home. In Brittany and Provence, some second-home owners had their cars vandalized—they had Paris license plates. In New York, the rich from Manhattan escaped to their summer houses on Long Island, causing local concerns about health services being overstretched. By giving access to mobility and outdoor space entirely new significance, the pandemic and post-pandemic shine a new flashlight on inequalities. In the first decade of this century, the number of Brits owning a second home abroad doubled. Every third new home built in Spain was a holiday home. There are some three million vacation homes in France. Who has access to them, and who has not? Ten percent of the population of Paris escaped to the country before lockdown went into effect, but 90 percent stayed behind.

Karl Marx distinguished between the bourgeoisie who controlled the “means of production” and the proletariat who did not. Post-pandemic classes may well distinguish between the cottage-ariat who control the “means of distance” and the claustrophobiat who are stuck in a flat without outdoor space. The balconariat will be the new petit bourgeoisie.

Almost 8 percent of Spanish people spent their quarantine stuck in an interior apartment without so much as a view of the street, let alone a balcony. A new status hierarchy is emerging. And second homes and private cars go hand in hand in the era of the coronavirus.

Looking for analogies for such private retreats, commentators tend to invoke Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron (1353), set in a villa in the hills to which the protagonists had fled to escape the Black Death in Florence. Or they point to today’s superrich and their well-stocked bunkers. A closer example is the socialist German Democratic Republic with its cult of the Datscha. Here, too, mobility was restricted, though by state power and the Berlin wall, but this made the private cabin and private leisure all the more important. A crowning design enabled owners to pitch a tent on top of the roof of their flimsy Trabant car. In socialist Poland and Hungary, DIY and home decoration were similarly huge. This retreat into a private world of “a thousand little things” may be an understandable reaction in a society where public life is controlled by a socialist state. For liberal societies, built on toleration and public exchange, such an internal exodus would be nothing short of an existential crisis.

Shopping is a microcosm of the transformation of consumer culture taking place in front of our eyes. In Britain, April delivered the sharpest drop in sales since the 1990s—including both physical and online shopping. By the end of the month, four in 10 shops had shut completely. America’s J.Crew soon joined well-known British brands like Laura Ashley and Oasis in bankruptcy.

Here again, we are seeing an amplification of preexisting trends, not a revolution. Dinosaurs like the venerable Stockmann department store in Finland had been struggling for years. All the virus did was to finalize its restructuring. For the last decade, shops on the high street have suffered from rising rents, decreasing footfall, and growing online competition. In Britain, 30 pence of every pound spent on stuff other than food was already spent online before the crisis hit; for food, it was still only about 7. The pandemic is now introducing many more to ordering with a click. Once digital baskets are set up, it is easy to continue filling them. Retail experts predict that by the end of the year, online’s 30 percent will have grown. Trends in other countries are in the same direction. More shutters will go down on brick-and-mortar shops in city centers.

At the same time, the pandemic has given a new lease on life to independent local stores. When it comes to food, especially, online delivery systems were unable to satisfy all the orders coming their way. Corner stores proved more flexible and stepped into the breach. In France, in early April, online sales of food were up by 98 percent—but next came rural shops (37 percent) and urban mini-marts (superettes; 25 percent), while the big hypermarkets saw a fall of 3 percent. If you really want flour, yeast, or eggs, best try your luck in your neighborhood store. Small farm shops, dairies, butchers, and many others enjoyed a renaissance in many parts of the world. As with culture and entertainment, we may be seeing a new emerging symbiosis between the big platform providers such as Amazon and lots of small, flexible shops—diffusion matched with decentralization.

All the gains made by online shopping, however, will not be enough to compensate for the serious drop in sales in physical stores. In early April, the Centre for Retail Research threw its old forecast for Britain out of the window. Even after documenting a mini shopping boom after lockdown, the group predicts a nearly 5 percent fall in total sales by the end of the year, amounting to a total loss of £17 billion. That’s a lot of unsold merchandise and empty cash registers.

The repercussions of the great retail downturn will be widespread. To take just one example from the upper reaches of the retail market, many European luxury brands rely on Chinese customers to make up the difference between profit and loss. Gucci reopened its shops in China in early April, but its recovery looks partial at best. In China, luxury goods are not just about showing off but also about belonging—documenting that one has made it and arrived in the modern world. With China in recession, there will not only be a slowing down of frenetic urbanization and fewer new arrivals in the modern commercial wonderland. With trade and tourism disrupted, and international tension and xenophobia on the rise, the West and its branded symbols will lose some of their shine in the East. How many Chinese tour groups will in the next few years return to Milan and Lucerne to marvel at Italian accessories and Swiss watches?

Meanwhile, much of our working and domestic lives have moved online—and in the process, have come to mimic each other in ways that are both utterly predictable and quite surprising. What exactly is it that people are doing on their phones and computers at home in lockdown when they are not working? According to available data on U.S. and U.K. users collected at the end of March, most of what we now do is communication and entertainment—following the news (68 percent), listening to music (58 percent), watching movies (49 percent), playing games (40 percent). Twenty-eight percent of homebound digital consumers are searching for recipes, and 18 percent are watching fitness videos. These modes of domestic self-care were clearly more important than searching for fashion trends (16 percent) or vacations (12 percent). A survey asked 748 Canadians what they were doing more of. It hints at the emerging mix of physical and digital activities. Digital news and videos were on top (70 percent each) but followed by more reading (58 percent), more cooking (56 percent), and more time spent with family (51 percent); 44 percent played more video games, but 32 percent did more crafts. Stories from other countries suggest that some of these pursuits involve people rediscovering old hobbies, such as painting or playing with a train set.

At the same time, entire generations have been introduced to new digital technologies and forms of consuming—Houseparty had been popular with teenagers but has now been picked up by their parents; older generations are streaming opera and reading books online. Some of these new skills and revived habits are bound to stay. If, in addition, we assume that at least a portion of people will remain ensconced in their home offices, the new rhythm of physical-digital consumption will be with us for good.

In April, the Italian city of Florence asked families how they were doing with online education. Twelve percent said they found it difficult because they did not have enough tablets or computers for everyone in the household. This is a worrying figure in several ways—for the one in eight children who will be left behind, but also for what it tells us about the density of digital machines that affluent societies now take for granted. For it effectively means that 88 percent have enough multiple devices in their home to work, learn, and consume simultaneously. How many children and seniors who do not yet have a smartphone or a laptop will find one under the Christmas tree this December?

All our online work, streaming, house-partying, and exercise is made possible by vast data centers that depend on power and lots of cooling to prevent overheating. In 2018, the digital sector was responsible for 4 percent of the energy footprint and 2 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in the world (the same as aviation); in Europe, it is responsible for 10 percent of all electricity consumption. Then, experts predicted that the figures would stop rising, because people would switch from big computers to smaller, more efficient smartphones, and because there was a limit to the demand for video and other streamed services in “mature” markets. Those may have been reasonable assumptions in 2018, but they look silly now. Few parents today will want their children to write their essays on a smartphone, let alone to deprive themselves of the newest streamed miniseries.

So far, we have talked about the taste preferences and habits of people staying at home. But who lives in the home varies tremendously. Today, 40 to 44 percent of households in Sweden, Norway, and Finland are occupied by a single person; in Japan, it is 35 percent, in Germany, 42 percent; among rich consumer societies, the United States is an outlier to the overall trend of single-occupancy homes, with just 28 percent. In the fascination with the “sharing economy,” it was easily forgotten that housing—one of the most precious things in people’s lives—has been shared less and less in recent decades. The rise in solo living has had many causes. Some of it is involuntary and has to do with old age and being widowed, some with shifts in lifestyles among the young, some with housing policy. Living alone has big knock-on effects once there is the expectation that you should also have your own private washing machine, TV, and other appliances. In Finland, some new one-person apartments are built with their own private saunas.

When the coronavirus hit Europe, Swedes were joking that it would not be much of a problem for them, because they were naturally good at “social distancing”; since then, the number of deaths in Sweden, sadly, has far exceeded that of their neighbors. For people elsewhere, the question should be: Will the virus turn us into physically aloof Scandinavians? By promoting a habitus of keeping our distance, the virus may complete the triumph of solo living. Yes, the experience of isolation may push some to look for partners and roommates. But for many others, their own flat will now be their safe space. Architects and designers of “smart cities” had many innovative ideas about “co-living” arrangements, with shared kitchens, washing machines, and entertainment rooms. Who will want that now? In many existing co-living homes, communal areas are currently closed.

Lockdown has triggered a frenetic search for moral guidance and reassurance: Turn the crisis into an opportunity! Focus on the things that really matter! Contemplation, not consumption! As in the world Depression of 1929–32, our crisis has been good business for moral prophets and self-help guides. Reinhold Messner, the first man to climb Mount Everest without supplemental oxygen, preached that renunciation brings fulfillment. That is easy if you are isolating in a flat in Munich and have your own castle in South Tyrol to return to; Messner had flown in from Ethiopia, and his mountaineering feats are not entirely innocent when it comes to the cult of productive leisure.

How are people responding to these exhortations to make the best of isolation? The Finnish Literature Society has asked people to record their lives during the pandemic. For some, distancing has been liberating. “In a world that forces me to be an extrovert, I can finally be an introvert,” one 18-year-old woman wrote. For mothers with small children, by contrast, lockdown robbed them of the little solitude and leisure they had. A 32-year-old single woman said at the end of March that she was getting “really angry” at all those feel-good people telling everyone to focus on “the essentials” of life and that they were “all in it together.” For her, Covid-19 was not a liberation from a consumerist treadmill; quite the contrary, “Corona has taken (almost) everything from my life I enjoy—meetings with friends, cultural events, my hobbies, … the experience to meet new people, travel to other cities and countries.” The internet was a “lousy” substitute. People, in her view, had not pulled together but apart, with everyone spying on everyone else to check they kept their distance and did not meet with friends. For her, the pandemic meant “loneliness, anxiety and disappointment.”

The great coronavirus lockdown is clearly destined to change our lives as consumers—a change that will encompass not just how much but also how we consume. As we’ve seen, the quantitative downturns generated by lockdown conditions are grim though relatively straightforward. The greatest recession the world has seen in a century inevitably will hurt a lot, even with all the pain relief administered by central banks. People will have less money in their pockets, and at the same time prices for food and most other goods will rise. Since spending on health care is going up (also a form of consumption), this means households will have even less money to purchase other goods and services.

This is to say nothing of longer-term upheavals to our collective disposable income, such as a looming pension crisis for the elderly. At the same time, more households will depend on handouts and social transfers from the state; “public social spending” was around 23 percent in the rich world in 2019 and is unlikely to fall. And a 15 percent drop in consumption over the course of the year will leave a lasting footprint throughout the consumer economy. All the disinfected baskets and plastic sheets between seats and tables will only save so many shops, hotels, and restaurants. By the end of the year, many will be bankrupt and gone. We will be served by a new mix of online platforms, local stores, and private shoppers. Decentralization and flexibility will rule. The 24/7 consumer culture will triumph. Distancing is already leading to staggered service and more flexible opening times in shops and restaurants. Online work and consumption are carving up what is left of the weekend.

However, the qualitative effects of the crisis may well produce the longest-lasting impacts. We still reflexively tend to treat consumption as an output of work and money: We work and get paid, or receive benefits, and then we buy something. When economists and central bankers present their forecasts, this is the kind of thinking underpinning it. But consumption is also an input. The way we consume shapes the way we live and work. And the coronavirus is changing this. Lockdown is not a conveyor belt that initially moved activities into the home and then can presumably be reversed at the crisis’s end to roll them out again. Distancing is changing the nature, intensity, and distribution of activities. If just some people continue to do more cooking, jogging, reading, streaming videos, and drinking cocktails, but do less eating-out, take part in fewer group sports, and take fewer trips to music festivals and foreign lands, this will have major repercussions for our economy and culture. Many recovery forecasts currently rely on a brisk “bounce back” in the consumer economy; their tacit assumption is that people after lockdown will tighten their belts but otherwise resume their old habits. But history shows that this is not very credible. We know from wars, droughts, and energy crises that such disruptions are not temporary breaks; they are instead force multipliers that simultaneously amplify earlier trends and reorder daily life in ways that carry on thereafter.

When we talk of the “new normal,” it is easy to forget that the “old normal” was once new. The notions that each person should have their own home, eat out, fly to Ibiza, exercise, take at least one hot shower a day, and change their clothes constantly—these are not inborn human rights, and were indeed regarded as exceptional before they established themselves as normal. The history of consumer culture since 1500 is a succession of many such new normals. They come and go, but they are never simply the result of changes in getting and spending. They have been aided and steered by politics and power.

Our taste for sugar and coffee, for example, would have been inconceivable without the brutal intervention of empires, slavery, and plantations. Likewise, the fact that the majority of people in the rich world right now live in their own home, have mortgages, and look at their electrical gadgets or a loaf of bread baking in their oven would be impossible to explain without reference to public policy support for homeownership, the purchase of the first refrigerators, and investment in infrastructures. The mass diffusion of TV sets, private cars, and modern bathrooms since the 1950s was not just a clever plot by Madison Avenue; it was made possible in part by the rise of welfare and unemployment benefits, public pensions, and public housing. Via such critical subsidies, the postwar state helped ordinary and vulnerable people to get a foot on the ladder of consumer society.

Our own still-evolving new normal will similarly depend on what kind of lifestyle our states, cities, and we as citizens want to promote in the new age of distance consumerism. Do we want a “rebound” or a new direction? Are we going to invest in new runways or in bike lanes; make balconies and allotments part of new housing standards or leave such questions to be answered by the market? Will we subsidize drive-in opera or local music schools? Can we provide communal sports grounds with body temperature monitors or reserve those for the professionals? Do we plan to give people the right to roam across fields and beaches as long as they keep their distance, and will we continue to protect second-home owners’ right to exclusive privacy? We are looking at a long list of possibilities that cry out for public debate, political vision, and leadership.

Unfortunately, we have seen very little of it so far. From Manhattan to Milan, mayors have made a pitch for more walking and cycling. National governments, by contrast, have mainly distinguished themselves by silence or by competing with one another about who can get their citizens back to shops and beaches as soon as possible. A charitable explanation for this uneasy stasis would be to say that, of course, governments have been under unprecedented pressure and had to focus on the immediate public health crisis. How could one expect them to lay out visions of the future when tens of thousands of their citizens are dying? Fair enough. But hidden in the forecasts and the way governments have been looking at the future after lockdown, we can also see certain protocols of thought that are instinctively favoring certain ideas of normality and editing out alternative futures.

In the United Kingdom and Sweden, especially, ministers have talked about the need to adapt public health policy to their societies’ code of “behavior.” In this context, “behavior” has mainly stood in as a crude version of behavioral economics and reduced possible instruments of intervention to one form or other of state-assisted “nudging” in the formulation of former Obama regulatory czar Cass Sunstein. Nudging has undoubtedly worked in solving some particular problems; the classic case in the United Kingdom is the switch in 2015 from “opt-in” to “opt-out” pensions that has raised the number of people saving for retirement. That is all for the better.

Unfortunately, the challenges presented by our current and future lifestyle represent an entirely different scale of social problem. The U.K. Behaviour Insights team, which was formed by the British government in 2014 and also has offices in New York, Sydney, and Singapore, came up with two practical recommendations in the course of April. One proposal used behavioral insights to create a text service for the National Health Service. The other plan allowed for online delivery companies to use a preset default to nudge people to choose having no contact with the delivery person. At a time of major crisis, when we are wondering how we can or should live in the future, these efforts seem woefully out of proportion, and indeed more than “loneliness, anxiety and disappointment.”

I say all this as a historian who has dabbled in the social sciences, not as an economist or psychologist. I tend to deal with the past, not with forecasts or behavioral laboratory experiments. But I do know how societies in the past tackled crises and thought about the future. And I can assure you that many of them had more insight, vision, and courage to change their ways of living than we hear today from our leaders and their chosen experts. One of my favorite examples comes from Japan. In 1919, the Everyday Life Reform League (Seikatsu kaizen dōmeikai) was formed. Set up by the Home Ministry, the league had support from architects, schools, local communities, and housewives’ associations. It set out to promote modern living, health, and thrift. League leaders urged homemakers to give up kneeling on the floor and cooking with polluting charcoal, in favor of standing upright in a modern kitchen that ran on clean electricity. Gift-giving, elaborate ceremonies, and male-only hobbies were to yield to rational budgeting and a focus on what today would be called “quality time” with the family. Of course, not all of their visions came true, nor should they have; the kimono has not completely disappeared. Still, anyone who has visited Japan will instantly recognize the triumph of many elements of the new-normal lifestyle sponsored by the league more than a century ago.

Far-reaching change is possible, in other words. But the success of the league also reminds us of the political resources and commitment required, not just from the state but from across civil society—including from ourselves, the consumers.

We are all consumers now. That is why we are at the same time so powerful and so powerless. Car manufacturers, by contrast, are a much more concentrated lobby. How we consume and live our lives is not just a private matter; it always creates profound repercussions for our communities, the nation, and the planet. The people who boycotted slave-grown sugar or clothes made in sweatshops understood this. In 1908, the first generation of consumer groups met for their international congress in Geneva. They had a simple motto written on their banner: “To live is to buy. Buying is power. Power is duty.” Their message is as relevant today as it was then: Consumers as citizens have power. Financial stimuli and credit holidays are welcome, but these economic measures can only do so much. At a time of unprecedented crisis like ours, we need more than ever to harness consumer power if we want to prevent the new normal from ending up a social and environmental disaster.