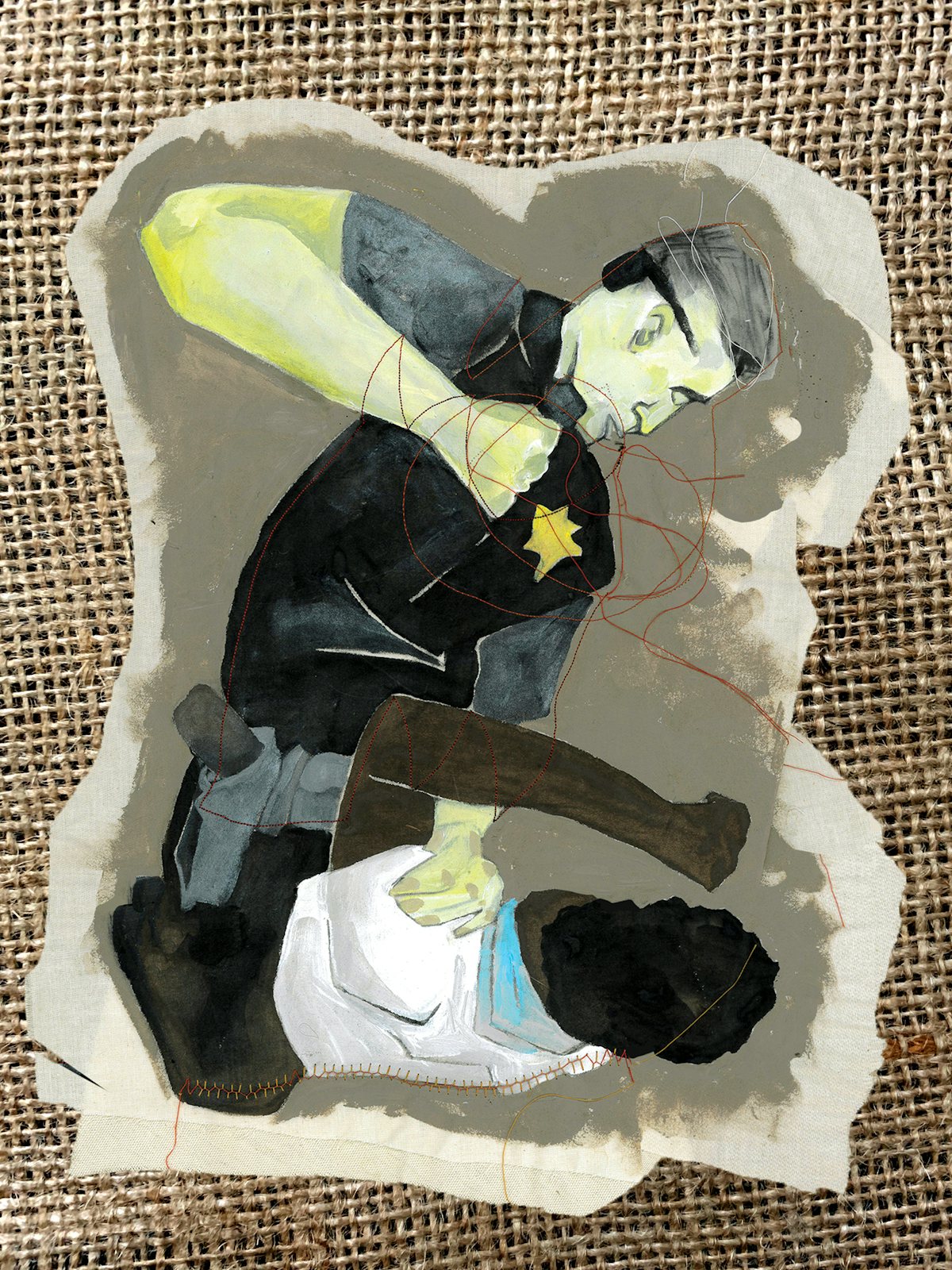

The summer of 2020 will be recorded as a once-in-a-generation uprising against police brutalization of Black people. The multiracial protests that erupted in all 50 states seemed to break the embargo—at least momentarily—against the official acknowledgment of the continuing legacy of anti-Black racism in American policing. Fueled by the video-capture of the casual hand-in-the-pocket–style murder of George Floyd, this mass repudiation might be read as an expression of the humanitarian values that the brutal slaying of Floyd flagrantly violated. But as the 24-hour coverage and daily analysis of the uprising revealed, the regime that produced Derek Chauvin and the still-uncharged killers of Breonna Taylor is not a broken one: It continues to work as it was designed to.

The deeper functions of American policing were revealed every night that breathless reporters told harrowing stories of protesters smashing windows with considerably more urgency than they relayed news of police officers smashing heads. Not even the frightening descent into a lawless police state could trump the anxiety over a possible takeover from the bottom. Cable TV viewers watching the commentary and recaps of the president’s terroristic attack on peaceful protesters in front of the White House by an unidentified national police force were suddenly interrupted with the urgent story of a local drugstore break-in on the other side of the country—the perpetrators having long since departed from a scene that was miles from any active protests.

The reflexive treatment of erratic outbreaks of looting as a more ominous threat than the organized massing of state terror also speaks volumes about the nation’s real civic priorities. Consternation over the loss of goods rather than the incalculable loss of eyes, limbs, and lives points to the bedrock realities on which modern policing is built. It was not simply that the vicious response of police to the mass protest (while the entire world was watching) was unexceptional. It was the violence-enabling pearl-clutching about looming social disorder that reminded us yet again that mainstream thinking is just as powerfully organized around the fear of the bogeyman as the nightmares of childhood are. This particular bogeyman is a phantom born of slavery, a fear embedded in the DNA of post-slavery society grounded in the recognition that orchestrated and professionalized violence might not be enough to preserve the shaky foundations of racial hierarchy.

The fear of being outnumbered and overrun by the indignant and unforgiving masses is that thing that goes bump in the night—the gnawing insecurity that the paddy rollers in the antebellum countryside would take care of while the misnamed keepers of the peace tucked in the owners and the elites for the night. Generation after generation, they do their work out of sight, as the descendants of the slaves and the descendants of the guardians play the same unchanged roles, only occasionally brought into unforgiving light by the dawn of freeze-frame technology.

I saw firsthand how the white elite, stuck in the bogeyman nightmare, gave their tacit approval to the ugly work of their guardians when a white woman invited neighbors in a tony university neighborhood to hold up a Black Lives Matter sign at the corner. All hell broke loose at the very thought; local business owners closed their shops while their landlord threatened to sue her for the loss of a day’s business. All this for a sign expressing what should be the simple promise of living an unterrorized life in twenty-first–century America.

Such episodes are all-too-vivid reminders that the hopeful talk about the current reckoning may well return to its familiar and limited outlines when the fundamental question is raised: How can we imagine a better future without first contending with the darkness that underlies the pervasive fear of Black people? In a white supremacist society, that fear is like muscle memory. When the baseline of the social order is slavery, when the freedom-seeking self-help behavior of running away was called theft, how can any policing be anything more than fundamentally racist—regardless of who is playing the role of the police?

In order to prevent yet another reversion to the status quo of white moral panic, we need to prod the emerging new discourse around racial justice and policing to engage the deeper question of how we might reckon with, and finally dislodge, this toxic muscle memory that continually disfigures our body politic.

Beneath the facade of law enforcement is a steady barrage of incidents like the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, in which the police and the institutions that hold guns would rather sustain white supremacy—whether it’s legal or not—than substantiate any anti-racism. These episodes again reflect the original design of American policing, and focus on its larger context and purpose.

Scholars like Robin D.G. Kelley have recently reminded us that American policing is designed to protect property. In an interview with The Intercept, Kelley notes that original paddy rollers had one job: to recapture any and all escaped Black people and to return them to the owner.

The deployment of paddy rollers—the corps of white vigilantes who are etymologically and ideologically tied to modern police patrols—would rise and fall in concert with the paranoia of white elites haunted by the bogey of a slave revolt, of the sort that Toussaint Louverture led in Haiti in 1791. When the threat of revolt was in abeyance, slave owners would seek to institute checks on the paddy rollers’ violent and destructive excesses—until, that is, the fear of a slave rebellion surfaced again. What many liberals unschooled in this basic history are wholly unwilling to say now is that the core function of the police isn’t to protect every person from a randomized form of personal and property trespass but rather to protect white people against the larger population of subordinated people.

My colleague Cheryl Harris laid out the property-protection foundations of modern policing in her 1993 Harvard Law Review article “Whiteness as Property.” Its crucial insights show how current oppression remains embedded in these formative and interconnected forces of American racism and property ownership. According to Harris, property rights are “contingent on, intertwined with, and conflated with race.” Today’s policing is a remarkably sturdy and long-lived adaptation to this racist social order, and still conforms to its fundamental directive—to protect racialized American property. This mandate always transcends liberal America’s cries for reform.

In post-slavery—and post–policing-of-slavery—America, racist policing in the American slavocracy was also tied to partnerships with the private violence of organizations like the Ku Klux Klan. That’s why lynchings and other extralegal acts of white supremacy were reinforced by the firm hand of the U.S. government, as in the Tulsa Massacre of 1921. It’s also why the legal system continues to forbear any serious effort to confront lynching and other forms of extralegal violence to the same extent that the state tries to police alleged trespasses within anti-racist movements.

Indeed, white supremacist groups in America have never been subject to the same crackdowns that are continually unleashed on anti-racist groups. The clumsy and misguided initiative from the Trump administration to label antifa a terrorist organization may look at first like another burst of flailing incompetence—but in fact it is grounded in the firmest of American traditions: state intimidation of those fighting for equality.

From 1956 to 1971, the FBI ran a Counter-Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO) intending “to expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize the activities of” civil rights groups by engaging in tactics such as wiretaps, blackmail, spreading disinformation, raiding offices and homes, fabrication of evidence and perjury at trials, vandalism, and exposing targets to violence and death.

Though COINTELPRO has ended, the FBI’s desire to destroy Black activism has not. COINTELPRO operated under the guise of investigating radical Black extremism and violent Black nationalism or separatism. The FBI continued to dedicate its resources to combating “Black separatism” long after COINTELPRO was dissolved in scandal in 1971.

In 2017, the FBI coined the term “Black Identity Extremism” (BIE) in direct response to increased Black activism and the growing Black Lives Matter movement following the killing of Michael Brown. By 2019, the threat previously described as BIE was grouped with White Supremacy Extremism (WSE) as two forms of the same kind of violence—Racially Motivated Violent Extremism. These allegedly equivalent tendencies were treated as a threat on par with ISIS, justifying a major program of surveillance, investigation, and infiltration.

Yet there is no similarly vigorous arrangement to interrogate the underpinnings of the likes of Dylann Roof and Timothy McVeigh—white men hell-bent on the production of whiteness-as-ideology–infused attacks on dissenting and nonwhite Americans. Just between the two of them, Roof and McVeigh claimed far more lives than any “BIE” has over the course of half a century. In Roof’s case, he did so specifically in a Black church in South Carolina. His massacre was targeted and lethal—and it has not been met with anything like the same institutional force that has persecuted and injured peaceful Black people advocating that their loved ones not be killed by police. Instead, Roof and others like him are labeled lone wolves, their ideologies—much like Trump’s—dismissed as fringe.

These facts point us toward a troubling but essential fact: that the behavior of police in the United States has hardly been about law enforcement; it’s instead been about the protection of a very particular status quo. And that status quo is tied directly to the maintenance of the inferior status of Black people. It is a calculated legal institutionalization of white dominance that’s been kept in place for all of American history.

During World War II, many Black soldiers were sent across the world to defend the lauded principles of this racially segmented nation. This was supposed to be a great unifying national crusade—the flattening of difference in the face of a true common enemy.

And yet, Black soldiers in Germany were tasked with cleaning the latrines of German prisoners of war, they were asked to sleep at the foot of flooded hills, and they were driven from German businesses by white American military police. In this very publication, in 1945, a Black soldier wrote, “You hear a lot of stuff about how homesick the overseas American soldier is for the good old USA. But you don’t hear much of that from the Negro soldier. Not the ones in Europe. Anyway, not the ones I know, not the ones in the 41st Engineers. Hell, why should they be homesick? Homesick for Jim Crow, for poll taxes and segregated slums? Homesick for lynchings and race riots?”

When Trump boosts references to “white power”—and when we describe Trumpism as the politics of white nationalism—we must collectively recognize that such a claim is grounded in a layered history of coerced white superiority. And no matter the context surrounding it, this obsessive focus on the preeminence of whiteness remains central to the concept of America.

It’s clear that American government has mirrored the intersectionally racist ills of society, and reinforced them at home and abroad. This brutal form of social mimicry harks back to philosophical concerns of Mary Wollstonecraft, who wrote more than 200 years ago of her fears that government would merely serve as the all-powerful arm of scalable oppression. When we see the operations of the white supremacist state from this vantage, it should be no surprise that the June killing of a Black federal security officer in Oakland by Air Force Sgt. Steven Carrillo has gotten little attention, whereas the fantasy threat of antifa, Black “thugs,” and “identity extremists” remains central to the entire political establishment’s discourse.

Carrillo has since been tied to the so-called boogaloo movement, and officers found that his clothes were festooned with symbols—and that his social media profiles actively engaged the claims of this white-national–identity group. FBI Special Agent Jack Bennett says Carrillo and his co-conspirator Robert A. Justus Jr. used Black Lives Matter protests as a cover for their plans to attack law enforcement. In his getaway, Carrillo wrote—in his own blood—“BOOG” on the hood of a hijacked car.

If the backlash to police reform were really about protecting the police, this story would be shared by every Blue Lives Matter “advocate” in the country. It would have warranted a robust response from friend-of-the-police Donald Trump, and it would have brought about the intensive, widespread response of federal law enforcement that the specter of “looting” provoked in the aftermath of George Floyd’s killing.

But that’s not what the pro-police backlash is about. It’s about white supremacy. So when the person doing the killing is a white supremacist, it hardly prompts a response. And it certainly doesn’t spark any law-and-order tweeting from the Oval Office, or any outraged yelling from the Trump-aligned golf carts in The Villages, Florida.

Again, the explanation here is painfully simple: The fear of marauding Black masses undermining white people’s well-being, security, and lives is more horrifying than actual terrorists conspiring to kill Black cops. Until this undercurrent of alarm is ferreted out, and our racial bogeymen confronted in their true and full profile in the light of day, we cannot begin to untangle the close relationship between policing and the white supremacist social structure that policing props up.

The call to defund the police might thus be framed more accurately, and broadly, as the mandate to dismantle the hyper-militaristic, racist functions of the police as the coercive power of white nationalism. In other words, defunding the police needs to be a call for the de-weaponizing of white supremacy.