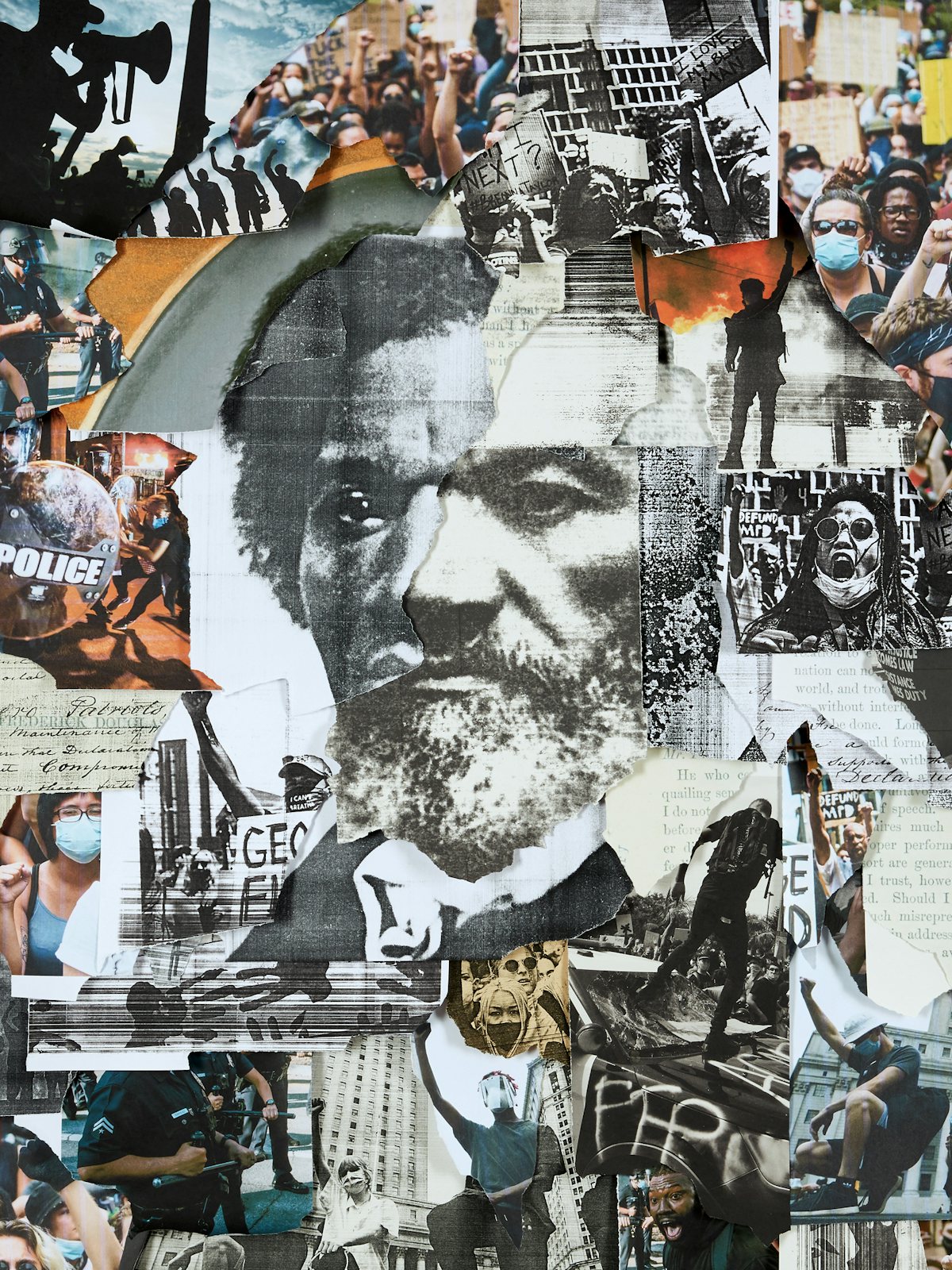

As our country grapples with a deadly pandemic, responds to still more outbreaks of police brutality, and bears astonished witness to street after street filled with fed-up citizens calling for change, I find myself thinking of Frederick Douglass. The former slave, orator, political organizer, and self-taught man of letters in many ways speaks to the present moment of civic and racial fracture almost as powerfully as when he scourged the conscience of white America in the mid-nineteenth century.

Indeed, it’s no exaggeration to say that Douglass’s legacy—and indeed his very image—continues to haunt the urgent quest for real and enduring racial justice in twenty-first–century America. After Douglass found a wider audience in 1842 as the well-spoken protégé of William Lloyd Garrison’s Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, he went on to become—alongside his many other celebrated accomplishments—the most photographed American of the nineteenth century. His image has remained a steady presence in our time as well, and not just on film. According to the Douglass scholar John Stauffer, in addition to 168 photographic portraits, the great man’s face graces “the walls of fifty neighborhoods; seventeen schools or universities; seven libraries or historical societies; seven community centers; five public housing projects; five government buildings; five churches; three stores; three playgrounds and parks; two prisons; two underpasses; one fire station; one newspaper building; one publishing house; and one subway station.” This vast roll call of Douglass mural sites and building names neatly distills the aspirations and deferred promises that continue to define so much of black experience two centuries after his birth.

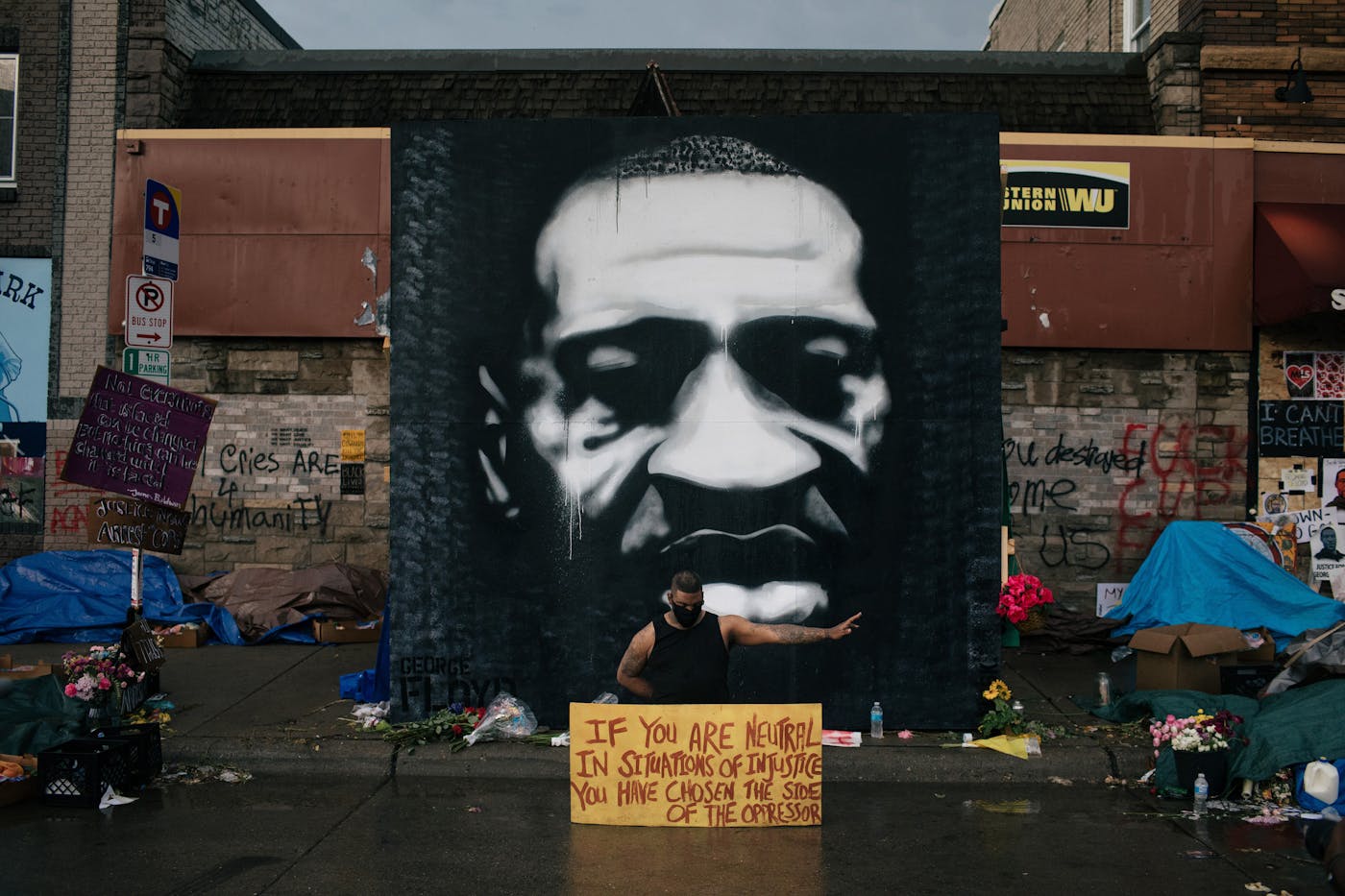

Douglass almost never smiled while posing. In presenting himself as sober, dignified, confident, he refuted prevailing stereotypes that cruelly caricatured African Americans as carelessly content with bondage, while also furnishing vivid and unassailable evidence of black equality. He hoped his white viewers would see him and his kinsmen as, well, kin. “Whether we read Shakespeare or look at Hogarth’s pictures, we commune alike with nature and have human beings for society,” Douglass wrote in a lecture called “Pictures and Progress.” “They are of the earth and speak to us in a known tongue. They are neither angels nor demons, but in their possibilities both. We see in them not only men and women, but ourselves.” Douglass anticipated the evocative power of recorded images a century before photos of police dogs attacking civilians helped tame the Klan in Birmingham, and even longer before cell phones captured police killings of Eric Garner, Walter Scott, George Floyd, and so many others.

He also knew that countering the narrative of delusional white supremacy was a double-edged sword; too much information aimed at exposing its brutalities could bring new and unintended forms of harm. He bristled at other authors of slave narratives who included a surplus of details surrounding their escape from bondage. It was best, he argued, to leave some edges blurred. Here, too, Douglass’s cautions echo down through today’s agitations for racial justice: Some protesters demonstrating in response to George Floyd’s murder asked their supporters to stop sharing their photos on social media. We serial tweeters may believe we’re acting in the spirit of Douglass when he observed, “It is evident that the great cheapness and universality of pictures must exert a powerful, though silent, influence upon the ideas and sentiment of present and future generations.” In reality, though, such images now possess an ominous underside—and present a new opportunity for the racial surveillance state: By trafficking in cheap, universal images of today’s uprisings, we may just be thoughtlessly exposing our friends to facial-recognition technology. Discovery in Douglass’s time could mean a return to slavery or a violent death. For modern protesters, it can also result in death (as it may have for six Ferguson activists after 2014) or having their names and addresses publicly released over Facebook Live—as St. Louis Mayor Lyda Krewson did in June. Krewson’s actions helped spur a demonstration demanding her resignation, which in turn yielded an iconic image of an affluent white St. Louis couple brandishing firearms at the peaceful demonstrators marching past their downtown mansion. In the long-standing American tradition of evasion and violent eruption around the foundational wounds of race, the image of black demands for justice and accountability once more had seamlessly been translated into the charged register of white existential rage. And that, in turn, produced heightened black vulnerability, in a fraught dynamic Douglass mapped out in striking depth a century and a half ago.

The legacy stretching alongside that of Douglass’s image is, of course, his singular literary voice. Douglass’s three autobiographies resound with the sort of moral indignation and impatience with the folklores and cant of established powers that we associate with the prophets of the Hebrew Bible. In addition to his courage and ferocious intellect, his candor sears through every sentence. At no point in his long, public career did he suffer fools gladly. He “rejected empty politeness,” as his recent biographer David W. Blight put it. Benjamin Quarles, an African American and author of a landmark earlier study of Douglass’s life, noted that his subject, shaped by the bludgeoning invective of his mentors, “developed no sense of the precise shadings of the nouns and adjectives he used in reprobating his opponents.” Maybe. I like to think of Douglass as fully aware of the properties of shade-throwing—that he was a “firespitter,” to borrow a phrase from the poet Jayne Cortez, steeped in thunder and lyricism.

A mimic of cruel and legendary accuracy, Douglass mixed wit, pathos, and a fondness for intellectual brawling to become a storyteller who kept listeners riveted to their seats. Because he understood the power of narrative so well, he emerged as a relentless foe of American hypocrisy and the critic most capable of using the language of American exceptionalism to expose the nation’s ludicrous and deadly pretenses. Every civilization depends on myths and stories to shore up its foundational creeds, and to stabilize its emotional and philosophical infrastructure. America’s myths stand out because they don’t just insist that the United States is as noble and powerful and wealthy and wise as any other civilization before it—but also that the American nation is greater at all of these things and will forever endure as the standard-bearer of a birthright so magnificent as to be holy. Even as new forms of entertainment and technology introduce key variations to this animating myth, they are sustained at bottom on language—the living, serpentine text that slithers through, and lends definition to, every American epoch. Douglass readily recognized the primal force of the language of civic rebuke and redemption, and adapted the American reliance on fable and text to suit not only his ends but also those of his enslaved and abused brethren. In one speech delivered near the end of his life, called “The Lessons of the Hour,” Douglass leveraged the idea of America’s exalted status on the world stage to call out the enormities of white supremacy by their true names.

“We claim to be a Christian country and a highly civilized nation, yet, I fearlessly affirm that there is nothing in the history of savages to surpass the blood chilling horrors and fiendish excesses perpetrated against the colored people by the so-called enlightened and Christian people of the South,” he thundered. “It is commonly thought that only the lowest and most disgusting birds and beasts, such as buzzards, vultures and hyenas, will gloat over and prey upon dead bodies, but the Southern mob in its rage feeds its vengeance by shooting, stabbing and burning when their victims are dead.”

It’s important to grasp Douglass’s vision as a literary one, steeped in the broad currents of American myth, as opposed to a narrower exercise in political exhortation. Like the Garrisonians and evangelical revivalists who raised him up in abolitionism, Douglass was initially suspicious, even disdainful, of the political process—the assemblage of institutional compromises that had rationalized and extended American slavery. He saw the Constitution as fundamentally flawed, what the author Marilynne Robinson recently described as “a compact among a few rich men.” This meant that the conduct of politics in the American constitutional order was inherently corrupt. The task before him and other serious apostles of radical reform was to change hearts and minds, not laws.

This unstinting view became tempered, however, the longer Douglass himself sought to advance substantive change on the American political scene. Over time, Douglass came to see the futility of moral suasion and the usefulness of turning the professed ideals of the Constitution to his purposes. That document was limited, yes, and embodied an intolerable effort to shun ugly truths in its failure to mention slavery apart from the tortured language of the three-fifths compromise. But even at its flimsiest, Douglass conceded, the founding document offered more potential for summoning the forces of justice than an outright, fastidious rejection of policy and legislation. At the annual meeting of the anti-slavery society in Syracuse in May 1851, Douglass declared his view that the Constitution should be “wielded in behalf of emancipation.” In a column in his newspaper The North Star, he reaffirmed this position. His change of opinion, he wrote, “has not been hastily arrived at.”

This realization marked a turning point in Douglass’s public career—one that he stolidly adhered to until his death in 1895. In his last major speeches, he was still challenging his white countrymen to “have loyalty enough, honor enough, patriotism enough, to live up to their own Constitution.” In choosing the American Constitution over the American conscience (such as it was), Douglass outstripped the righteous despair of his mentors. (William Garrison notoriously burned a copy of the U.S. Constitution, denouncing it as a satanic compact for its role in formalizing the political reign of the Southern slave power.) In the process, Douglass also came to serve as a uniquely American role model—an exemplar of uppity Negroes everywhere. Garrison and the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society had helped Douglass rise from a laborer’s life of uncertainty by hiring him as a lecturer and providing him with a salary. They paid him to move audiences with his first-person tale of suffering under the lash and to express gratitude for their generous intervention; they didn’t pay him to think. But Douglass’s independence wasn’t for sale; never again would he be owned.

Douglass may have been a standard-bearer of uppitiness, but he was far from its only apostle. Against improbable odds, self-assured colored people were popping up everywhere. James McCune Smith, John Mercer Langston, Charles Lenox Remond, Harriet Tubman—all of them free and determined to free others. Most showed no tolerance for colonization or other schemes designed to sidestep the problem of slavery rather than confront it head-on. As with today’s protesters bent on undoing centuries of corrupt law enforcement, they found the difference-trimming mantra of “reform” to be insufficient; it was abolition or nothing. Just as Douglass came to abandon moral suasion, he also gave up relying solely on debate and peaceful protesting. Douglass scoffed at the suggestion that he should gradually and politely wait for his oppressors to come around to his way of thinking. Finding common ground with his sometime rival Henry Highland Garnet, in August 1863 he conceded, “It really seems that nothing of justice, liberty, or humanity can come to us except through tears and blood.” Five months earlier, he had published his famous recruiting broadside, “Men of Color to Arms!” In urging black men to fight for the Union, he envisioned a nation stripped of its crippling prejudices and rebuilt from scratch, on genuine republican principles of equality and justice.

It was hardly a novel notion. The original Framers had similar thoughts when they declared themselves independent; “we have it in our power to begin the world over again,” as Thomas Paine declaimed in Common Sense. Lincoln, too, had extolled the sacred right of the people “to rise up and shake off the existing government, and form a new one that suits them better.” Not for nothing was the period following the Civil War called Reconstruction, after all. It ultimately failed—with long, tragic consequences for African Americans. W.E.B. Du Bois described its overthrow as “a determined effort to reduce black labor as nearly as possible to a condition of unlimited exploitation and build a new class of capitalists on this foundation.” A far cry, in other words, from what Douglass and the abolitionists had in mind. Nonetheless, the opportunity to tear up the country and begin again from the ground up has continued to tantalize activist imaginations at key junctures in the struggle to advance the cause of racial equity. During the civil rights movement’s “Second Reconstruction” over the 1950s and ’60s, Martin Luther King Jr. dreamed boldly of little black boys and girls holding hands with little white boys and girls—an image of another, better America that remains maddeningly elusive more than half a century on. Even over the brief span between the death of George Floyd and today, we’ve likewise already glimpsed the promise of a thorough overhaul of the American ideal, as protesters give greater context to police brutality by addressing other systemic inequities such as the lack of universal health care, substandard schools, and the need for a minimum basic income. They’ve pointed out that civilian review boards, bias training, and body cams won’t even fix law enforcement, let alone the far deeper ills of a profoundly broken society.

And at the outset of this renewed agitation for what might be a Third Reconstruction in the making, it’s crucial to again engage the question that remains at the core of this country’s racial despair: Dare we try once more to make good on Frederick Douglass’s prophecy of a genuinely new American order of the ages? Can African Americans hope any longer that such a thing is feasible, or would the embrace of such a radical possibility simply set ourselves up for massive disappointment, yet again? Most discussions of this nature drift toward talk of managing expectations, and segue into the sober counsel to steer clear of pessimism and reclaim a hard-won faith in things still unseen—the “stone of hope,” as King memorably phrased it. But as we wait to see what sort of movement emerges out of the present popular mobilizations against racist police violence, I worry that the search for silver linings or cosmic meaning is an unhelpful distraction. Sure, some of us need to see hopeful portents when cops kneel in sympathy and kids gratefully accept ice cream cones from kindly patrol officers. But how audacious is hope, really? Is it any more useful than robust skepticism? A certain wariness of hope doesn’t automatically translate into self-indulgent despair—despair being, as James Baldwin noted, a luxury only white men can afford.

Rather, a disciplined aloofness from hope is the chastened brand of knowledge forged in experience. Even a casual student of history can detect the seesaw character of black struggle in the United States, its motions calling to mind nothing so much to a pendulum swinging back and forth just above our heads, often at an uncomfortably perilous close remove. Emancipation, followed by sharecropping. Reconstruction, followed by massive voter suppression, land theft, and convict leasing. The civil rights movement, followed by more residential segregation, white flight, and urban renewal. Toxic waste and lead paint pointing the way to for-profit policing, school-to-prison pipelines, payday loans, and—lest we forget—greater black exposure and fatality levels in the Covid-19 pandemic. Even now, with unprecedented numbers of white Americans marching beside us in the streets, it still makes sense to look over our shoulders for the coming reverse swing of the pendulum.

Aside from his attendance at colored conventions, as they were then called, Douglass conducted his public life almost solely in the company of whites. And thanks to his pronounced distaste for making nice, his relationships could be contentious. After he broke with William Lloyd Garrison, they spent the rest of their lives ensuring that they would not turn up at the same place at the same time. Douglass was proud to be one of 32 men (and the only black person) at the historic Seneca Falls convention of 1848, where he signed the Declaration of Sentiments affirming the rights of women. He was friends with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, but their bond unraveled two decades later, when the Fifteenth Amendment promised to give the vote to black men. Stanton, furious that women had been cast aside, derided black men as “Sambos” and likely rapists. David W. Blight writes that both women “denounced the Republicans and allied with white-supremacist Democrats” in the wake of the dispute.

Douglass’s struggles to maintain friendships among the white allies of his day were likely equal parts personal and political. But even so, they uncomfortably anticipated a host of kindred questions arising from the immense demonstrations that erupted after Floyd’s death. As one recent New York Times article has asked, are whites protesting because they believe in the cause or because it’s trendy? It was hard to tell with so much virtue signaling running amok in those first few weeks of the George Floyd uprising, with white folks racing to declare their support for Black Lives Matter and rushing to check on their one black friend. (One oft-quoted study concluded that 75 percent of whites don’t have even so much as one such friend.)

Facebook timelines presented whirlwind collages of contradiction: White expressions of support and solidarity—including, in some places, lining up between police and people of color—barely keeping pace with frantic footage of white people throwing tantrums in parks, restaurants, and public spaces. In the background, we also saw news of craven declarations from problematic companies (such as Starbucks’ initial refusal—since reversed—to allow employees to wear attire to work emblazoned with the Black Lives Matter slogan), overdue removal of racist branding (Aunt Jemima), and the flourishing of useless gestures (goodbye, master bedroom!). An awkward spotlight was thrown on certain sports teams’ monikers (in addition to the egregious example of the Washington NFL team’s name, a bevy of familiar but still offensive names have come up for fresh debate—the Chiefs, Indians, and Braves, to cite just the biggest-market offenders). Meanwhile, Tina Fey, Jimmy Fallon, and other media eminences scrambled to atone for and/or remove blackface performances from their not-so-distant pasts.

The best consequence of the frantic ass-covering was its demonstration of how wispy and ill-considered white Hollywood liberalism often is. (Or maybe not just Hollywood; I remember one colleague forswearing Frappuccinos in April 2018, after black men were arrested in Philadelphia for failing to order lattes in a timely manner—a gesture of anti-racist solidarity that lasted about a week, all told.) That said, I acknowledge the value of having glamorous notables dip a toe in the waters of social justice. Like images of Marlon Brando and Paul Newman at the 1963 March on Washington, a passionate tweet from Taylor Swift has the potential to move millions. Recently on social media, I saw a post praising Betty White for her leadership in helping integrate a ’50s-era TV show—followed almost immediately by a post recalling her performing in blackface with the other Golden Girls.

Who’s woke? Who isn’t? Who’s canceled? Who’s not? While we ponder these riddles, white people are lambasting small, black-owned bookstores for their slowness in supplying the anti-racism books they’ve ordered in a not altogether seemly rush to be educated ASAP on the bitter cultural legacies of white supremacy—a curriculum of self-reform presented, mind you, in books written by white people expressing ideas that black authors have been advancing for years. Amid the shredded remnants of traitor flags and spray-painted monuments, the ironies and uncertainties abound. Robert E. Lee’s stone-carved likeness might be lying face down in the street, but the customs and beliefs he embodied are far sturdier.

Could Douglass have been gazing into our present when he observed that “the settled habits of a nation” are “mightier than a statute”? It’s no wonder some of us regard our newfound allies with jaundiced eyes, half expecting them to pull a Susan B. Anthony and release their inner Karens. Still, a movement requires a critical mass, with more numbers than African Americans can muster by themselves. Polls show white attitudes toward black lives may be improving, in a way that might produce real change. Perhaps we can find comfort in that development the next time we’re watching footage of white men in camouflage and hunting caps storming state Capitols in protest, stroking their assault rifles as they shout.

By 1893, Douglass was a lion in winter. Battle-weary but still stouthearted, he eased from the role of righteous firebrand into that of gracious mentor. Among the most influential figures he shared his wisdom with was Ida B. Wells. A brilliant, intrepid journalist, she’d left Memphis just ahead of a lynch mob that had destroyed her printing press. Another protégé was 21-year-old poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, whose apparently immortal poem “We Wear the Mask” has regained currency in this era of Covid containment.

If not for the gender prejudices of her time, Wells would likely have emerged as Douglass’s heir apparent. She still became a productive and respected leader, a founding member of the NAACP, and a valuable chronicler of racial violence. It’s easy to see Wells’s leadership qualities in the women whose vision and strategy have shaped the movement for black lives. It’s indeed impossible not to wonder if some of the criticism they attracted during the early days of the Ferguson uprising stemmed as much from their gender roles as from their position outside traditional civil rights circles. What’s more, the decentralized structure of the new movement confuses folks used to a top-down model of movement politics dependent on a single, charismatic leader. One thing this new generation of movement activists does not lack for is charisma. Alicia Garza, Patrisse Khan-Cullors, and Opal Tometi, the three women behind BLM, are by this time well known; the same is true of Bree Newsome Bass, a creative artist and activist perhaps best known for removing the Confederate flag from the South Carolina statehouse grounds. None seem much interested in building a personal brand. The struggle continues to be top priority.

“We have a lot of leaders,” Garza said in an interview with The Guardian, “just not where you might be looking for them. If you’re only looking for the straight black man who is a preacher, you’re not going to find it.”

As Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor and others have pointed out, the groundwork for the current movement was laid by community leaders unknown to many of us but with credibility to spare among their constituents. And for those who complain about a lack of specifics, there are policy proposals aplenty. Taylor writes, “Women like Mary Hooks from Southerners on New Ground in Atlanta and Miski Noor and Kandace Montgomery of the Black Vision Collective in Minneapolis have been at the center of articulating new demands for redistributing resources away from policing, prisons and billionaires, and back into public programs.”

Some of their ideas mesh comfortably with Douglass’s long-ago vision of a republic completely reinventing itself. “People like me who want to abolish prisons and police, however, have a vision of a different society, built on cooperation instead of individualism, on mutual aid instead of self-preservation,” activist Mariame Kaba explained in The New York Times. “What would the country look like if it had billions of extra dollars to spend on housing, food and education for all? This change in society wouldn’t happen immediately, but the protests show that many people are ready to embrace a different vision of safety and justice.”

There is, of course, a forbidding, all-too-familiar litany of obstacles in the path of Kaba’s goals: an underwhelming Democratic presidential nominee who has already responded half-heartedly to calls for defunding the police; an unhinged, overtly racist Republican incumbent incapable of minimal coherence; a stultifying Supreme Court; obstinate police unions hindering the reform agendas of progressive-minded prosecutors; spineless state legislators and corrupt mayors. Just thinking about any one of those roadblocks is enough to put a cramp in anyone’s optimism, despite the energy and intensity of our present moment. Writing in 1870, Douglass warned his black readers to avoid getting so mesmerized by a sense of possibility that they could no longer determine which goals were realistic. He cautioned against getting caught up in a “delirium of enthusiasm.” It’s a good phrase—and still good advice.