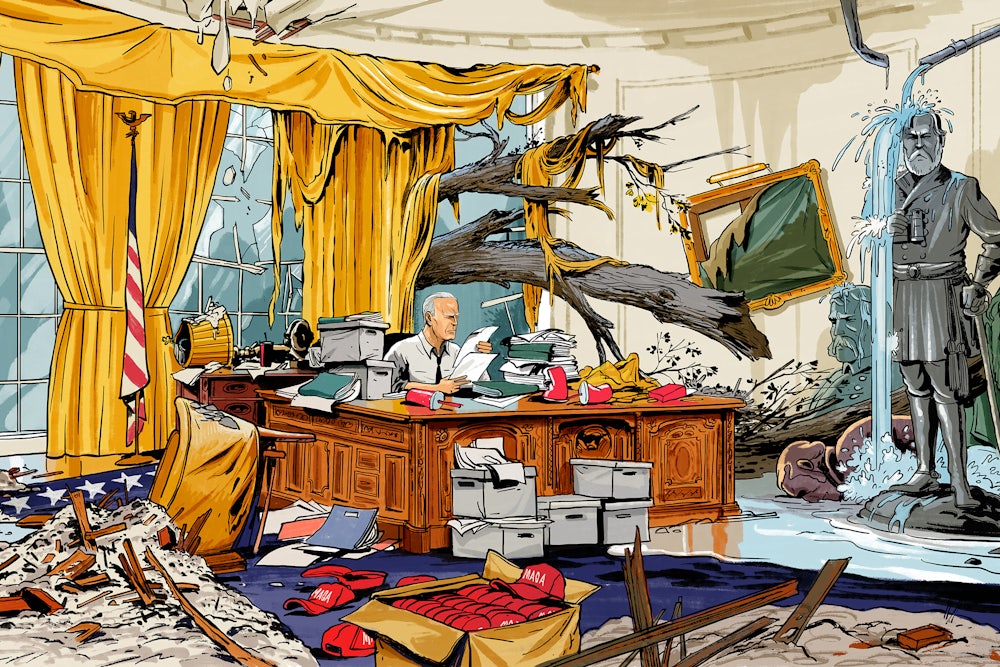

Provided that the polling of late summer holds (a big “if” in presidential politics), on January 20 Joe Biden will—as a late bloomer on par with Grandma Moses—have finally achieved his life’s great ambition at age 78. As he moves into the Oval Office after his inaugural address and the congressional luncheon, Biden will face the worst set of crises buffeting America since the nineteenth century.

Only Franklin Roosevelt, taking the oath on a cloudy and gloomy March day in 1933, inherited comparable challenges. But the Depression was only an economic catastrophe, and Herbert Hoover, paralyzed though he may have been as president, was an honorable man. Barring a dramatic turnabout in the country’s fortunes, Biden will confront joblessness, disease, and the hateful legacy of the most lawless president in history. Much as in 1933, when establishment figures such as Walter Lippmann suggested that America required a dictator for the duration of the economic emergency, the country will greet Biden’s first year in office as a crucial test of whether our battered democracy can again flourish.

These existential questions mean that the pundit’s traditional late-campaign thought experiment of envisioning a Biden presidency requires an imaginative leap far beyond position papers and policy speeches. So many issues that were points of conflict during the Democratic primaries now seem—in the midst of a pandemic—as peripheral as John Kennedy and Richard Nixon squabbling over Quemoy and Matsu, two insignificant islands off the Chinese coast, during their 1960 debates. With Trump in apparent free fall after his disastrous Tulsa rally and his race-baiting embrace of Confederate statues, Biden, for the most part, has traded policy specifics for periodic reminders that he is neither a hate-monger nor a low-rent huckster peddling miracle virus cures from the White House.

Specifics are also in short supply for the simple reason that these days everyone in the Democratic Party, with the possible exception of John Edwards, can claim to be a Biden policy adviser. Like any traditional presidential candidate running a big-tent campaign, Biden distributes titles with the lavishness of a shady trace-your-British-ancestry firm. In addition to the campaign’s policy staffers and longtime outside advisers to the former vice president, Biden and Bernie Sanders with great fanfare in May announced unity task forces to supposedly meld the centrist and progressive wings of the party. In mid-July, the task forces unveiled an ambitious $2 trillion climate change plan (without explaining how it would get through a closely divided Senate) that prompted Trump to risibly claim that Biden wanted to “abolish the suburbs.” (The president did not explain where he thought Biden planned to put the existing land around cities.)

After nearly four years of Trump, it is hard to remember what a normal presidency feels like. And predictions of the shape of a Biden presidency are hampered further by the inability to predict five months before the inauguration how ravaged the nation will be by both Covid-19 and the deep recession that’s accompanied the pandemic. Trump’s own behavior in defeat will add another wild card to the deck. Will Trump then spend November and December denouncing the legitimacy of the election? Or will the rejected president sulk in the Oval Office watching cable TV until on inauguration morning he storms out of the White House after hurling the remote at a deviationist episode of Fox & Friends?

What we do know is that in his first days in office, Biden will be forced to rebuild America’s virus-fighting capacity from scratch; devise a major economic stimulus program; reassure our allies and confront Vladimir Putin over meddling in our elections; decide how and whether to prosecute the lawlessness of the Trump regime; propose legislation on police reforms, protecting the Dreamers from deportation, and the expansion of Obamacare; and weigh the fate of the filibuster in the Senate. All this will be happening as aides and outside groups loudly remind Biden of his other campaign promises on issues ranging from global warming to student loan debt.

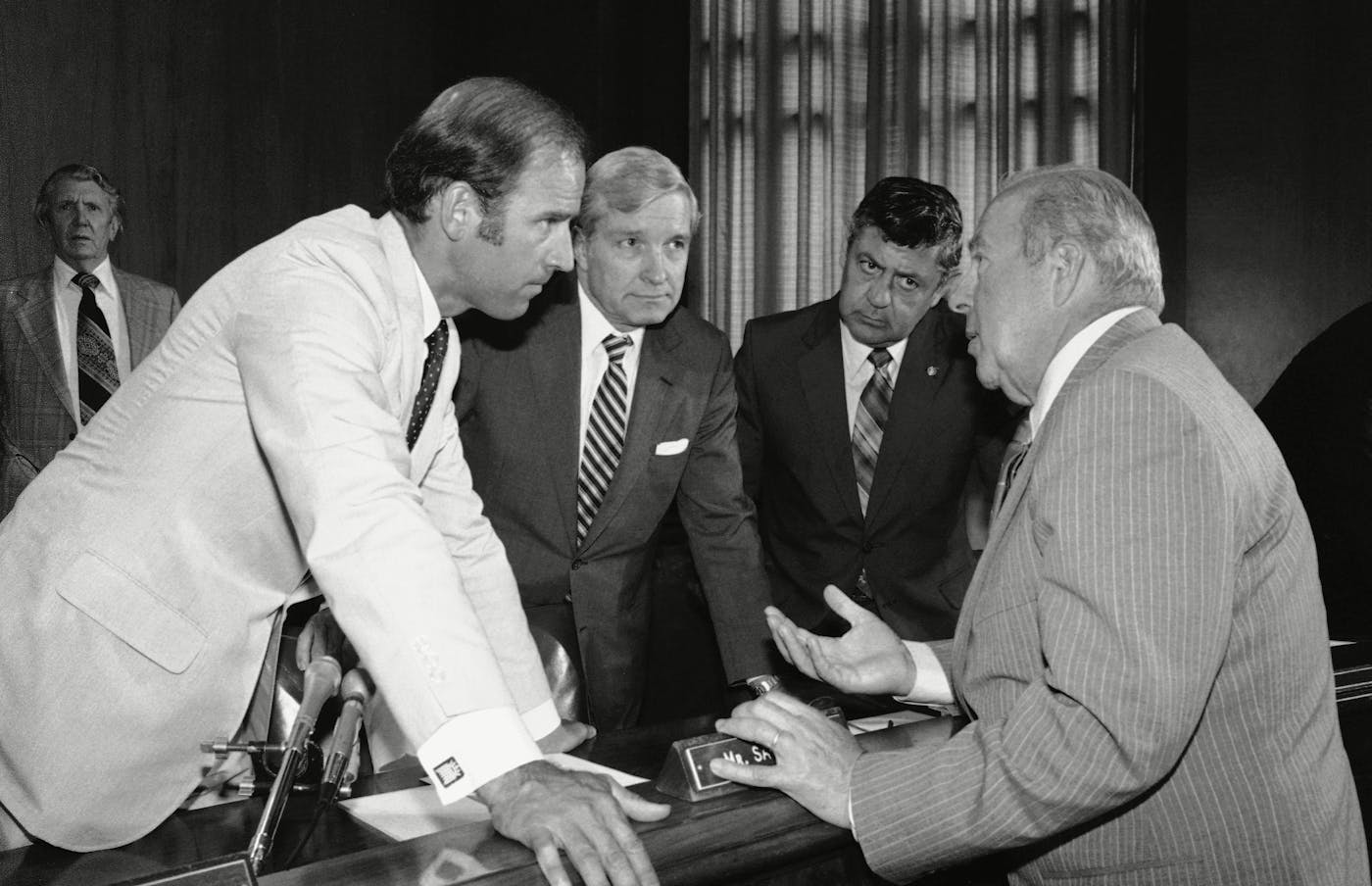

After nearly five decades in Washington, Biden is an institutionalist, a political leader who believes in consensus and gradualism. But Biden also was shaped by the Kennedy years (“moon shot” is one of his favorite concepts), and he had a key role, as vice president during the 2009 economic meltdown, in pushing for as big an economic stimulus as Barack Obama could sell to Congress. As a result, Biden grasps the necessity for boldness in a crisis—while also intuiting the political risks of going too far too fast.

Biden also understands a president’s most precious commodity—time. Every day a President Biden spends on the coronavirus is a day that he is not fully concentrating on the fate of his economic legislation on Capitol Hill. Every trip to Europe to renew bonds with Angela Merkel and Emmanuel Macron takes time away from domestic concerns. All the while, the clock is ticking toward the 2022 congressional elections. As a great survivor of politics, Biden knows firsthand that both Obama and Bill Clinton lost their House majorities after two years and had to govern for the next six years through executive orders and Capitol Hill compromise.

For all the grousing on the left about Biden’s lack of inspiration, he would come into office with more relevant experience than any president since Lyndon Johnson. Biden’s long Washington résumé means that he understands that half-forgotten concept called governing. As Elaine Kamarck, a veteran of the Bill Clinton White House who is now a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, put it, “The specifics of Biden’s policies almost don’t matter that much. The big thing will be a return to normalcy in government, even if the virus is still raging.”

A presidential administration is typically forged during the frenzied 11 weeks between the election and Inauguration Day. As seriously as Biden takes preelection planning (and the former vice president’s transition teams are already at work), little of importance can be decided before the election. The reason has nothing to do with superstition or hubris. Rather the simple reality is that Biden, like any candidate, will be too preoccupied with running for president to focus on being president.

A presidential transition is a formal process with government-provided office space for the incoming president’s team and expedited security clearances for would-be national security officials. Historically, presidential transitions have been a model of bipartisanship, even after heated electoral battles. “There is no case of a conflicted transition,” said Heath Brown, who is a professor of public policy at the City University of New York and the author of a 2012 book on transitions. “There have been some frictions like between Carter and Reagan in 1980. But we have no example of an outgoing administration trying undermine a transition.”

Even if Trump balks (and it is amusing to imagine what piece of advice the forty-fifth president will leave behind in the traditional letter to his successor), the beaten-down senior career officials in each Cabinet department will undoubtedly welcome their liberators from the Biden team. The mountain of memos produced by transition officials in various offices will undoubtedly paint a bleak picture of a federal government hollowed out by Trump’s scorched-earth battle against competence. Biden policy director Stef Feldman said in an interview, “You can’t overstate the decimation of the federal workforce under Donald Trump. The task for our transition teams will be immense.”

And during the transition, every Democrat with policy or campaign experience will spend long hours staring at his or her phone, praying for a text message or a call with a summons to interview for a top Biden post. Newspaper op-eds will be written and cable TV appearances will be arranged with the single-minded goal of appealing to the Biden transition team. Already, speculation is rampant about the makeup of the Biden Cabinet and the likeliest appointees to other key administration posts. But the lists tend to recycle the same names—mostly 2020 presidential candidates and prominent members of Congress. So if you’re looking for a Democrat with military experience, it’s usually Pete Buttigieg. Amy Klobuchar gets mentioned for attorney general. In May, there was even a flurry of rumors that Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez would be Biden’s ambassador to the United Nations.

Don’t bet on it. Instead, the pattern has traditionally been that the best way to earn a top job in a Democratic administration is to have served in a mid-level post the last time around. Still, there are hints from within Biden Land that this will not simply be an administration of former officials climbing a rung or two higher on the career ladder. The expectations for increased diversity in the year of Black Lives Matter represent part of the rationale. But Biden’s transition team will also reckon that the multiple devastating crises they will inherit require more than a résumé entry as an assistant secretary in the Obama or Clinton administrations.

During his transition, Biden will also launch some of the most fateful tactical discussions of his presidency with Chuck Schumer and other Senate Democratic leaders. The topic: the future of the filibuster, which currently requires a daunting 60 votes to get most legislation through the Senate.

Of course, this scenario assumes that a Biden sweep will bring in enough Senate challengers to give the Democrats a 51–49 or even a 52–48 majority. Until recently, these fantasies seemed implausible. But based on the polls, Trump’s summer swan dive has spilled over to his GOP enablers. So it seems a reasonable bet that Republican senators like Cory Gardner (Colorado), Martha McSally (Arizona), Susan Collins (Maine), and Thom Tillis (North Carolina) will be interviewing with D.C. lobbying firms in January.

As they map out their Senate strategy during transition, Biden and Schumer will know that the filibuster won’t be flatlined by a unanimous Democratic vote when the new Congress convenes on January 3. Senate negotiations take time—and some Democrats on the fence will need to be convinced that any kind of procedural compromise with Mitch McConnell is impossible. Biden, too, does not support eliminating the filibuster, although he recently said that he might change his position if the Republicans get “obstreperous.” But Biden can also count votes. And he will realize as president how daunting the alternative would be—trying to pass his ambitious agenda via reconciliation—a maneuver that permits a majority vote on fiscally related matters.

For all the talk of Senate traditions, the outcome seems pretty foreordained if the Democrats win a majority and the intractable McConnell continues as GOP leader. Negotiations over the rules of employing the filibuster might be possible if McConnell were replaced by the more reasonable John Thune, the current Republican whip. But otherwise, the filibuster likely will not last through the spring of 2021. “Based on my conversations with the caucus, it will be eliminated,” said Jim Manley, a former top aide to Harry Reid when he was Senate majority leader.

Biden’s transition planning has been built around constructing a set of options depending on the state of Covid-19 and the economy when he takes office. Of course, these assumptions may be revised on nearly a weekly basis during the period between election and inauguration.

There is only one certainty about the virus: The moment Biden takes office, it becomes his problem. Trump will have left behind the shambles of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other frontline forces battling the pandemic. Hard-line Republican governors like Ron DeSantis in Florida and Doug Ducey in Arizona may defy any restrictive orders from the Biden White House. Trump’s Fox News fan club may continue to refuse to wear masks. And drug companies will almost certainly try to pocket vast pandemic profits from any vaccine or drug treatment for Covid-19.

As dire as the medical situation may be in January, Biden will probably tread cautiously in promoting a vaccine. And the example he will heed wouldn’t necessarily be the successfully contained Ebola epidemic of 2014, but rather the bungled effort that President Gerald Ford mounted to develop a swine flu vaccine in 1976 when Biden was in the Senate. Not only did production problems mar the federal government’s initiative to warp speed the vaccine, but the public health crusade also ended abruptly when nearly 100 Americans reported being paralyzed from their injections.

When it comes to confronting an economy on life support because of the coronavirus, Biden would come into office with a major advantage—the new president and many of his key advisers would have been there before. The Great Recession was caused by Wall Street greed rather than a gruesome disease, but the need for economic stimulus is analogous to the crisis that Obama inherited. Back in 2009, Obama’s ambitions were hamstrung by Senate Democratic deficit hawks who were unduly panicked about the national debt. The Senate Democratic caucus has moved significantly to the left since then, so the only oratory about “seas of red ink” is likely to come from Capitol Hill Republicans—the same legislators who blithely ignored Trump running $1 trillion deficits in good times.

What kind of stimulus would Biden push for? The answer can partly be found by looking back at Biden’s record of overseeing, at Obama’s behest, the $787 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act approved by Congress in 2009. Biden prided himself on running a program with minimal corruption, and he proved to be a major critic of fanciful proposals. Michael Grunwald writes in The New New Deal, his book about the Obama stimulus, that Biden ended up blocking “260 Recovery Act projects that didn’t pass his smell test ... [including] a $120,000 Army Corps of Engineers plan to print brochures advertising a lake cleanup in Syracuse.”

As president, Biden would not be concerned with that level of micromanagement. What’s more telling is that in 2009 Biden was skeptical of any project—no matter how laudable the goal—that would take several years to provide a lift to the depressed economy. As Biden frequently said at the time, mocking long-range projects disguised as economic solutions to the immediate crisis, “They called it the Hoover Dam even though it opened in 1935.” (Hoover left office in early 1933.)

If the pattern holds, Biden would resist using a 2021 stimulus package on an all-out bid to repair the nation’s decaying infrastructure, upgrade rural broadband, and enact major components of the Green New Deal. Granted, Biden campaign advisers talk ambitiously about bold investments in the future, ranging from rebuilding the infrastructure to spurring production of clean energy. But to adapt a line from a long-ago British scandal, “They would say that, wouldn’t they?”

A crucial element of that challenge will be generous funding for unemployment insurance, a New Deal program that will celebrate its eighty-sixth birthday in 2021. At minimum, Biden in his first weeks in office will try to expand eligibility to cover some gig workers and permanently increase weekly benefits (though probably not as high as the extra $600 a week initially enacted by Congress). The overall goal, which may be too ambitious for 2021, is to turn the program into more of a European-style employment program with subsidies to companies to retain workers in hard times.

For many on the left, the initial Biden economic agenda will be disappointing. Such dejection will stem in part from unrealistic expectations for what can be achieved overnight by any president with a narrow Senate majority, even in turbulent times. But it also reflects a misunderstanding of Biden. Yes, he has moved to the left along with his party—and is willing to adopt policies that would have seemed to him extreme during the Obama years and his tenure in the Senate. But Biden is also a man of politics: a former senator who worries about getting too far ahead of the voters. And he is apt to temper his legislative ambitions based on polls and portents about the 2022 elections.

That said, Biden is likely to tilt in Elizabeth Warren’s direction on taxes. The political advantage, beyond reassuring the Democratic left, is that tax increases on high-income earners and corporations would signal that Biden is serious about the deficit and long-term budget arithmetic. As top Biden adviser Jake Sullivan put it, “The vice president believes that he can get the votes he needs on key elements of his tax agenda.”

There are also creative ways to reap massive tax dividends—and some that don’t even require legislation. Tax enforcement—especially in terms of scrutinizing the returns of the wealthy with often dubious tax shelters—has declined to its lowest level in decades. Former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, who is advising Biden, said, “Trillions can be raised in ways that will make the economy grow faster and fairer and not undermine incentives to work or invest.” Aside from the Wall Street Journal editorial page, it will be hard to find a place brimming with sympathy for the wealthy who behave as if they believe, as Leona Helmsley did, that “only the little people pay taxes.”

When Biden first ran for president in 1987, he portrayed himself as the embodiment of the Kennedy generation. As he said in those long-ago campaign speeches, “Just because our political heroes were murdered does not mean that the dream does not still live, buried in our broken hearts.” But in his second race for the White House in 2008, Biden presented himself as a mature statesman whose worldview had been honed by his years as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. More than anything, it was Biden’s foreign policy bona fides that prompted Obama to tap him as his running mate.

Indeed, without the coronavirus and double-digit unemployment numbers, Biden would have probably made foreign policy the centerpiece of his first months in office. Just as Obama won a Nobel Prize for not being George W. Bush, Biden would triumphantly tour the globe reminding world leaders that the Trump presidency was a horrible aberration rather than America permanently abdicating its traditional responsibilities. Think of the fence-mending that Biden will have to do after succeeding a president who wanted to pull the United States out of NATO; who humiliated our allies and genuflected before our foes; who preferred to get his national security advice from Fox News hosts; and who ran foreign policy as a shakedown operation for his business and political interests.

Biden, from his days as a senator and vice president, prides himself on personal diplomacy, but he won’t expect to revive America’s flagging global stature with a series of quick, “Hey, Angela, we’re back” phone calls. Sure, there is an easy symbolism to Biden immediately rejoining the Paris climate agreement and the World Health Organization. But foreign policy will be a major preoccupation of Biden’s first year in office, even if it has been barely mentioned during the campaign.

Begin with the Putin Perplex: How do you toughen sanctions to deter further Russian electoral meddling without the Europeans undermining compliance? The more details that emerge about Russia paying bounties to the Taliban to target American troops, the more political pressure there will be on Biden to constrain Putin. Tony Blinken, a former deputy secretary of state who is a senior Biden adviser, said in response to a question about Russia again meddling in the 2020 election: “Instead of claiming it didn’t happen as Trump did, taking Putin’s word over that of our intelligence community and feeding Putin’s sense of impunity, a Biden administration would impose substantial costs on Russia.”

The aggressive posture of China will present even more of a problem for the incoming president. To distract internal attention from China’s faltering economy, Xi Jinping has courted global disapproval by clamping down on Hong Kong, accelerating his persecution of the Uighurs, and even risking military skirmishes with nuclear-armed India. But the looming crisis for Biden may be an island just 100 miles off the Chinese coast. “The big danger is Taiwan,” said Michael Mandelbaum, emeritus professor of foreign policy at the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins. “The Chinese believe that the balance of military power is moving in their direction in the Taiwan Strait.”

The truth is that all presidents are governed by events beyond their control. The early days of the George W. Bush administration had been planned in advance like a business school case study, with binders dividing his presidency into six-month intervals. That hyper-organized approach to the presidency ended abruptly on September 11, 2001.

Once in office, Biden will immediately confront a legal question that has only a single precedent in American history: How does an incoming president handle his immediate predecessor’s suspected abuse of office? Gerald Ford’s pardon of Richard Nixon—although it helped end the national nightmare—was unpopular at the time and precluded any trial. But Nixon as president did not shield his underlings from federal investigation, which is why there was enough evidence early in Ford’s presidency to convict former Attorney General John Mitchell and former top White House aides H.R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman of illegally covering up the Watergate break-in and the broader scandals surrounding it.

There will be a political argument that going after Trump after he slinks out of the White House will only add to national divisions. But if you can’t prosecute a lawless president when he is in office and it is in bad taste to prosecute him after he has left office, about the only remaining legal option would be to prosecute him for thought crimes before he takes office.

Biden’s instincts point to the politically safe route of making the Justice Department as nonpolitical as possible. Only if the attorney general and other top officials have bipartisan credibility would it be possible to subject Trump to the rule of law that he mocked throughout his presidency. “The sobriety of these kinds of appointments and how they are made are as revealing as any policy or white paper,” said Bob Bauer, the White House counsel under Obama and now a senior Biden adviser. That is why Biden’s choice for attorney general may prove to be the most important personnel decision of his first year in office.

Sometimes during the primary debates, Democratic candidates gave the impression that ending the filibuster would be a miracle drug on par with Trump’s fantasy version of hydroxychloroquine—something that would cure all ailments from lumbago to loose teeth. In these reveries, congressional Democrats—without being hamstrung by the filibuster—would display a level of party discipline that even British parliamentarians might envy. Before long, the Green New Deal, Medicare for All, free college tuition, and a raft of new social welfare programs would be enshrined in law.

In truth, Congress—and especially the Senate—moves at its own pace. Passing the Biden stimulus and tax plans would probably eat up the bulk of time before the Easter recess. Imagine what might happen to the pace of legislation if, say, Ruth Bader Ginsberg announced her retirement and the confirmation of Biden’s first Supreme Court justice (as promised, a Black woman) took center stage in the Senate.

There is also another reality: The votes in the Senate simply aren’t there for large parts of the progressive agenda. Simple geography, rather than Chuck Schumer’s shortcomings as a vote-canvasser, is what’s likeliest to hobble most major climate change legislation. A Democratic majority would include senators from energy-producing states like Montana (Jon Tester and maybe Steve Bullock) and West Virginia (Joe Manchin). Throw in a timorous centrist like Arizona’s Kyrsten Sinema, and you’re already down to a maximum of 48 or 49 votes, even after eliminating the filibuster. Similarly, with tens of millions of Americans unemployed—many who never had the opportunity to attend college—it will be hard to muster massive support for millennials burdened with student loan debt. (Biden could, however, ease repayment terms through regulation.)

Biden’s priorities may well shift based on the economy and the political winds, but there are three pieces of legislation that fall into the must-pass category. Permanent legislative protection for the Dreamers would be an interim step signaling that, unlike Obama, Biden intends to make immigration reform a genuine priority rather than a glib campaign promise. Legislation to prevent the use of federal funds for the militarization of local police forces must also leap toward the top of the agenda in the wake of this year’s landmark Black Lives Matter protests. Finally, after more than a decade of paralysis, Biden would have the votes to repair and expand Obamacare—and, in all probability, add a public option.

If this is the extent of Biden’s first-year accomplishments, they will not go down in history as anything to rival FDR’s “100 days.” But compared to most presidents—especially those operating with only a tiny margin for error in the Senate—Biden would have compiled an impressive record. That’s especially the case given that Biden’s greatest achievement would not show up on the legislative ledger at all. His chief challenge—and it is devoutly to be hoped, his overriding legacy—will be to restore the soul of America and help lead the national recovery from an incompetent, race-baiting president with an unquenchable appetite for corruption and authoritarianism.