Pigs are flying! Up is down! The public approves of how Congress handled something!

After Wednesday’s much-anticipated hearing with the chief executive officers of Facebook, Google, Amazon, and Apple, onlookers in the media and activist community generally thought that the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust members showed up to show Big Tech what’s what. Coming on the heels of critically panned performances from lawmakers in their Tuesday hearing with Attorney General Bill Barr, this confrontation with the heads of America’s powerful tech monopolies offered some proof that incisive interrogation in the public interest was still possible.

Democrats like Chairman David Cicilline and Representatives Pramila Jayapal, Joe Neguse, and Mary Gay Scanlon evinced a deep understanding of the bullying built into each of the assembled firm’s business models. They brought clear evidence and rooted it in the letter and spirit of American antitrust law. While Republican Representative Jim Jordan spent his allotted minutes groveling for President Trump’s approval, Representative Kelly Armstrong warned about the constitutionality of geofence warrants, and Representative Ken Buck pressed Jeff Bezos about Amazon stealing concepts from proprietary conversations with startups.

It helped that the CEOs—especially Bezos—were clearly unaccustomed to other people actually challenging them. None had answers for their respective companies’ abuses. The best they could do was wanly mumble that Congress was mischaracterizing its pages of damning evidence and otherwise lean on the time-tested “I cannot recall” maneuver.

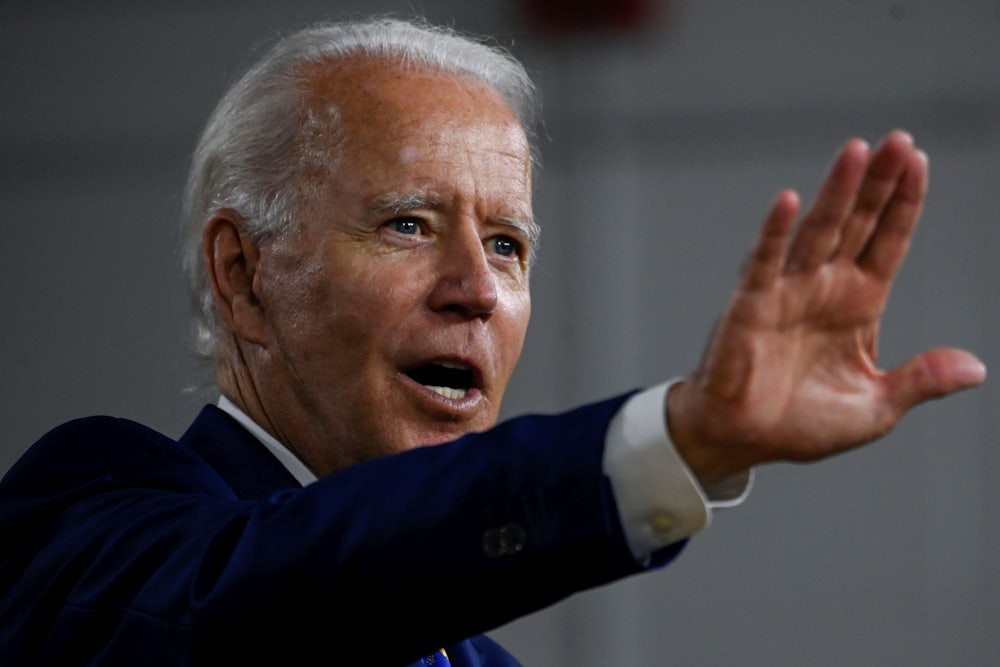

Overall, it was a rout in favor of the anti-monopoly movement. So policy-wise, what does it all mean going forward? Almost nothing, unless Joe Biden appoints strong personnel.

Throughout the hearing, the figures who really came off looking inept were the federal antitrust enforcement agencies—the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) antitrust division. These agencies already had most of the evidence Congress had on hand. Representative Jerrold Nadler presented an email showing Mark Zuckerberg bought Instagram out of fear that it could challenge Facebook—which federal investigators likely already had in their possession when the merger received the Obama FTC’s blessing in 2012. Representative Val Demings pressed Google’s Sundar Pichai about the company reversing its stance on merging data from its past acquisition DoubleClick—which Bush’s FTC could have prevented in 2008. One of Google’s lobbyists on that deal is now the assistant attorney general for antitrust.

Representative Lucy McBath played heart-wrenching audio of a small textbook seller restricted from competing with Amazon on its own platform. Folks, this is a practice that agencies and the public have had evidence of for years.

It’s important that Congress publicly shamed the tech barons. That fighting spirit will be welcome whenever they have the chance to hold the feet of monopolists to the fire. Nevertheless, it’s ultimately the FTC and the DOJ who will bring the necessary cases to break up Facebook, Google, Amazon, or Apple. Should Biden win in November, he’ll get to appoint the officials who will make these calls. Biden and his transition team should take the hearing on Wednesday as a clear signal that he needs to get these appointments right.

The easiest way to get them wrong would be to follow the path of least resistance and bring back the appointees of the Obama era. But they own a share in the failures that brought us to this point in the first place. Moreover, the career choices they’ve made since then should also indicate where their loyalties lie and whether it’s wise to welcome them back through the regulatory revolving door.

Biden’s close adviser Terrell McSweeny was an FTC Commissioner from 2014 to 2018, which means she was on the watch when mergers like Facebook’s acquisition of WhatsApp proceeded without challenge. She also let Uber off with a pittance of a fee after it lied about drivers in metro hubs earning as much as $90,000 (less than 10 percent of drivers made that much). These days, she’s a partner at Google’s preferred law firm, Covington & Burling.

Fiona Scott Morton ran the economics component of the DOJ antitrust division from 2011 to 2012, which means she was in power during the Facebook/Instagram merger. These days, she’s publicly repented and has asserted that it’s time to break up Facebook and Google. She’s not offered the same remedy for Amazon or Apple, however, perhaps because both of those companies have been paying her undisclosed consulting fees for an unknown period of time. She also went to bat for Microsoft when it acquired LinkedIn, Tesla in its fights with car dealers, and the travel website industry (itself consolidated into just two firms, Priceline and Expedia), all for lucrative fees. Three prominent scholars recently left her Yale University program out of moral indignation at her conflicts of interest.

When in power, McSweeny and Morton proved themselves unwilling to meaningfully enforce antitrust law. When out of power, they proved themselves unworthy of the public trust. And they’re just the tip of the iceberg: About half of the FTC’s antitrust lawyers since 2014 went into Big Law, defending the very corporations they used to investigate.

The burgeoning anti-monopoly movement in this country demonstrates that there’s a populist appetite to challenge the power of big corporations. This week’s Big Tech hearing showed that there are both strong cases to make for breaking up Facebook, Google, Amazon, and Apple and legislators with the stomachs to mount them. Should Biden prevail, he’ll enjoy a rare opportunity to take on a group of hated bullies right out of the gate and usher in a new progressive era of trust-busting. This can only happen if he picks the right teams to lead his antitrust agencies. Keeping people like McSweeny and Morton on the outside is a bare minimum first step.