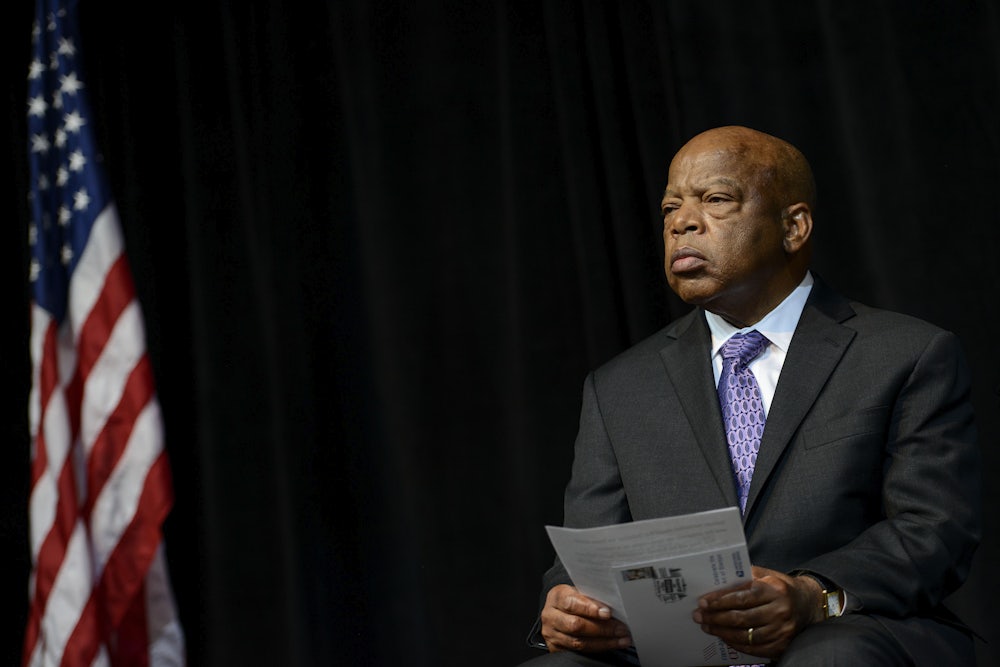

At ten past eight on a brisk Washington morning, Representative John Lewis of Georgia hurtled out of his cramped office suite in the Joseph P. Cannon Building and advanced on the Capitol a few blocks away. Burly and short (a little under 5’6”), he moved with the shoulder-heaving waddle of an out-of-shape former jock, though the only sport he has ever practiced seriously is protest-marching. More than thirty years ago, as national chairman of the legendary Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced snick), Lewis led civil rights demonstrations across the South and gained renown as a valiant, bloodied hero of the nation’s greatest domestic struggle this century. Now, as a Democratic Chief Deputy Whip, he carries that reputation into fresh battles.

At Room H-230 inside the Capitol, Lewis attended a breakfast for the Georgia delegation, skipped the bacon and eggs and managed a strained but civil exchange with Speaker Newt Gingrich. At 8:35, he was out the door, headed for a Democratic leadership meeting. Sequestered with his colleagues, he listened politely and, on this day, said very little, a calm and retiring presence amid their banter about Gingrich’s latest dip in the opinion polls. “Anyone who knows me will tell you,” he had warned between meetings, “that I am not a whooper.”

Lewis’s modesty is unfeigned, but it is also deceptive. After thirty years, his everyday affect remains gentle and sweet-tempered, the antithesis of slickness. When he does speak up, his rural Alabama inflection leads him to slur his consonants. Yet, when the feeling is on him, Lewis is capable of delivering, in the Southern Baptist style, some of the most stirring oratory to be heard these days in Washington. And, in his recent set-tos with the Republicans, he has emerged as a leading Democratic spokesman and an adroit and implacable partisan scrapper.

Less than a month into the new Congress’s first session, for example, Lewis began raising complaints about Gingrich’s financial affairs; and, soon after, he called upon the House Ethics Committee to investigate Gingrich’s videotape college course and his book contract with Rupert Murdoch. During the spring and early summer of 1995, while the ethics issue simmered, Lewis escalated his anti-Republican rhetoric, and snatches of it—“They’re coming for the children. They’re coming for the poor. They’re coming for the sick, the elderly, and the disabled”—started turning up on the network news and in the national press.

Lewis’s new, more combative stance has not gone unnoticed. Last August, after he participated in an Atlanta Labor Council demonstration against his Georgia Republican colleagues, a few of them questioned his fitness to serve in Congress. On the other side of the aisle, Minority Whip David Bonior has credited him for giving what Bonior calls “the Gingrich piece” of the Democratic strategy credibility. Jesse Jackson, meanwhile, told me that he has been buoyed by the return of “the vintage John Lewis.”

Now 56 years old, Lewis is the strongest link in American politics between the early 1960s—the glory days of the civil rights movement—and the 1990s. Despite some crushing personal and political setbacks, he has persisted in preaching the doctrines that overthrew Jim Crow: racial integration, nonviolence, economic justice and the “beloved community”—his favorite phrase, by which he means both an end and a means, the good society and the movement devoted to achieving it. At a time when prominent black nationalists and even liberals such as Tom Wicker dismiss integration as either a tragic failure or a synonym for mere accommodation, Lewis sometimes feels isolated. Yet he has doggedly kept the faith and advanced through the congressional ranks, gaining power and influence that would have been utterly inaccessible to a black Southerner a generation ago.

It’s a little surprising that of all the extraordinary SNCC organizers from the ‘60s—Robert Parris Moses, Julian Bond, Marion Barry, James Forman, Stokely Carmichael—Lewis has risen the highest. Thirty years ago, he was not known for his political skills or theoretical expertise. While more urbane SNCC intellectuals plotted strategy and studied Camus and Fanon, Lewis the grunt inspired the troops by quoting from Scripture and laying his body on the line. “John was not naive, but he made no claim to political shrewdness,” the former SNCC volunteer Mary King later recalled. Nor, at least until recently, did Lewis build much of a reputation in Congress as a powerbroker or policymaker. “He’s a big-picture person who always approaches an issue from a moral standpoint,” one Democratic staffer observed, “but he doesn’t get as much into the nitty-gritty of legislative minutiae.”

It is, rather, Lewis’s extraordinary personal aura and his moral consistency that commands respect. In an era when politicians, and especially members of Congress, are in bad odor, stigmatized as trimmers and cowards, Lewis “goes with my gut,” as he puts it, instead of heeding either powerful constituents or opinion polls. His eloquent speech in opposition to American entry into the Persian Gulf War—not a popular position for a Georgia politician to take—prompted Speaker Thomas Foley to tap him for the caucus leadership in 1991. Since then, Lewis has shown little hesitation in bucking large House majorities—and even, at times, his fellow Democratic leaders—over matters of conscience, as in his stalwart refusal to back federal laws expanding capital punishment.

Lewis’s bravery is not merely metaphorical. “In the middle of a bunch of courageous young people, he was the most courageous,” said Julian Bond, who served as SNCC’s press secretary. During the famous 1961 Freedom Ride, in Montgomery, Alabama, and again four years later in Selma, armed segregationists nearly beat Lewis’s brains out, leaving his head permanently dented and scarred. Like Bob Dole’s crippled arm, or John McCain’s sufferings as a prisoner of war, or Bob Kerrey’s Medal of Honor and artificial leg, Lewis’s civil rights travails mark an authentic experience of physical heroism of a sort that has become increasingly rare for Americans. Because Lewis earned his scars in a struggle to fulfill the promises of the Declaration of Independence, he shares with other civil rights heroes, living and dead, the mystique of a modern-day Founding Father.

All this makes Lewis virtually a Washington tourist attraction, a walking patriotic monument. “I think he’s an absolute saint, one of the few saints in public life, to this day,” said Burke Marshall, the distinguished professor emeritus at the Yale Law School and former head of the civil rights division at the Kennedy Justice Department. “Martin Luther King once said `that unearned suffering is redemptive,’” noted Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne. “By that definition, John Lewis is a redeemed man.”

The trouble with being a living monument, of course, is that you can end up with the political clout of one of the marble statues that line the Capitol rotunda. Lewis might have found himself turning into an icon of principled and doomed dissent. But anyone who watched him closely over the past decade would have noticed that somewhere along the line he acquired some practical political skills. In his first successful congressional race, in 1986, he exhibited a cunning, even cold-blooded campaigner’s intelligence—and wound up defeating his ex-comrade, Julian Bond, who had been heavily favored to win. In the House, Lewis has, from the start, worked hard to secure goodies for his district, including a $300 million federal building on a decaying edge of downtown Atlanta. And he seems to have figured out how to merge the past with the present, exploiting his moral authority and his SNCC experience in service to his party.

Congress, however, is not the street. “John ought to be in the top ranks of black leadership,” Julian Bond observed, “but he’s probably not, if you ask a hundred people on the corner.” Bond ascribed Lewis’s marginality largely to his normally unflamboyant style. “The leadership tends to go to flashier, showier figures, who may or may not deserve it,” he remarked. “People who are media-savvy and out before the public.” But Lewis’s difficulties run deeper than that. Although Bond insisted that most black Americans still share Lewis’s (and his own) integrationist “’60s values,” he also admitted that large and growing numbers, embittered by the rightward political drift of the past thirty years, have abandoned them, while a smaller number of black conservatives have, for very different reasons, grown skeptical of Lewis’s Great Society-style reformism. With this deepening polarization of black politics, Lewis’s position looks increasingly precarious. And sometimes even Lewis’s past contributions get lost in the shuffle. When high-profile journalists wish to evoke the black protests of the ‘60s, they are likely to trot out not John Lewis but Eldridge Cleaver or Maulana Ron Karenga.

Lewis has never had any truck with the new black Republicans. Nor, despite his public loyalty to the Clinton administration, does he embrace the neo-liberalism of the New Democrats (“What’s wrong with being liberal?” he asked). Yet, by refusing to compromise his integrationist principles, he has also distinguished himself from those black intellectuals and activists on the left, including Jesse Jackson, who have sustained fragments of the black-power romance, stood beside race-baiting agitators like Al Sharpton and struck tactical alliances with Louis Farrakhan’s Nation of Islam. “[T]he means by which we struggle must be consistent with the end we seek,” Lewis enjoined during a PBS debate with Sharpton in 1994, on the subject of anti-Semitism and Farrakhan’s lieutenant, Khallid Muhammad.

The breach between Lewis and his black critics caused a brief national sensation last October, when Lewis refused to participate in Farrakhan’s Million Man March and then denounced Farrakhan as a bigot on the networks and in Newsweek. Angry letters, faxes and phone calls poured into Lewis’s office from around the country; and for a time, it looked as if Lewis’s stand would guarantee him a tough primary race in 1996. For years, after all, there had been quiet complaints, in both Atlanta and Washington, that Lewis was too much of a party man, too chummy with whites, that he had lost touch with the alienated, hopeless inner-city mood. “He used to be a grass-roots leader,” grumbled Hosea Williams, once a top aide to Martin Luther King and now a community organizer in Atlanta, when I asked him about Lewis. Jesse Jackson, while singing Lewis’s praises to me, also remarked that he has sometimes shown a propensity to be “party bound.” Said Lewis aide Rob Basson: “They just feel that John Lewis isn’t black enough.”

Bob Herbert, The New York Times columnist, cautioned me about the media preoccupation with who is truly black. Herbert, who resents how white reporters and pundits have turned Farrakhan into a litmus test, finds it equally offensive even to mention Lewis and Farrakhan in the same breath. “John Lewis is a major figure in mid-twentieth-century American history,” he remarked. “The only reason to link him up with Farrakhan is because he’s black.”

Lewis, meanwhile, sees it as ironic that his integrationist vision could ever be considered moderate, let alone conservative. “When you talk about integration,” he told me, “some people think that it’s old-fashioned, that it’s out of date—that for a black person, it’s Tommin’, it’s weak, it’s passive. It is a radical idea. It’s revolutionary to talk about the creation of the beloved community, the creation of a truly interracial democracy, a truly integrated society.” His ideal of such a society is not, as his critics often imply, one of homogenization, whereby blacks would be forced to reject the heart and soul of their cultural heritage. “You can have an integrated society without losing diversity,” he insisted. “But you can also have a society that transcends race, where you can lay down the burden of race—I’m talking about just lay it down—and treat people as human beings, regardless of the color of their skin.” Yet he knows that, nowadays, there is an impression that his ideas are, at best, utopian, too trusting of white America’s good intentions. “People think I’m sort of weird,” he remarked.

As it happens, Lewis will face no opponent at all this year, either in the Democratic primary or in the general election. Thanks to an unusual Southern electoral coalition of working-class blacks and affluent white liberals and moderates, he has a lock on his Atlanta district; and the recent redrawing of Georgia’s congressional district lines has only strengthened his position. He takes his personal good fortune as a sign that the Farrakhan enthusiasms of last autumn were never terribly formidable, even among those who participated in the Million Man March.

Still, he sometimes worries that, on the national level, his old cause may have entered a self-destructive phase in which racial solidarity has become a cover for fanaticism. He has been disturbed, he said, by the zeal of some members of the Congressional Black Caucus always to “do the black thing,” an impulse that in 1994 led Kweisi Mfume to declare the existence of a “sacred covenant” between the caucus and the Nation of Islam (remarks that Lewis and his colleague Major Owens criticized, and that Mfume later retracted). He worries that the recent trend toward creating black-majority electoral districts will ensnare blacks in separate enclaves, the exact opposite of what the civil rights movement intended. He mocks younger, nationalist-oriented intellectuals and artists like Spike Lee who, he contends, have rewritten the past and romanticized figures like Malcolm X. “It’s a replay of what we witnessed during the late ‘60s,” he sighed, recalling the bleakest years of his life, when black-power chic blew SNCC to pieces, and the original civil rights radicalism fell apart.

At the Hunan Dynasty, an unpretentious outpost of upper Broadway on Pennsylvania Avenue, S.E., Lewis is a regular patron. Though it was late in the dinner hour, the hostess greeted us warmly and prepared a table in a quiet corner; and by the time the sesame noodles arrived, Lewis was running on with reminiscences of the ‘60s. We had already spent considerable time together, but sitting beside him I noticed, for the first time, the old, inch-long scar that runs along the left side of his head, the badge of a blow from a segregationist’s bludgeon.

Asked what he makes of his life thus far, Lewis recited some all-American, up-from-poverty cliches, but with the added twist that he felt as if he had been “picked up by the spirit of history.” He uses the phrase often, conveying neither pride nor pomposity but genuine wonder at his fate—and at how he has repeatedly found himself playing a leading role in so many momentous political events. Only gradually and indirectly, as he recounts these events, does he disclose the deeper story, of how an inexperienced, idealistic movement leader evolved into an astute, idealistic Democratic leader.

Had history not tracked him down, Lewis would today be a Baptist minister. Born in Troy, Alabama, in 1940, the third of ten children in a poor sharecropper’s family, he was gripped by an intense religious fervor at about the age of 7. Having been given charge of the family’s poultry yard, he began preaching to his captive flock, hypnotizing them with Scripture. “Chickens are very strange creatures,” he mused, though not nearly as strange as he himself appeared to his family. Forsaking his other chores, preoccupied with his ministry, Lewis severely tried his parents’ patience, especially when it came time to slaughter or sell off one of his congregants. Aghast, he would sob hysterically, boycott meals and refuse to speak for days on end. “My first nonviolent protest,” he recalled dryly, only half-kidding.

Describing his boyhood, Lewis talked of the everyday indignities of segregation, of a widespread feeling of resignation among his neighbors and kin, and of the spectre of violence, some of it deadly, on both sides of the color line. “I grew up in a home with a shotgun over the door, and a rifle in the corner,” he said. “On a Saturday night, you heard where people were being shot, where people were being cut and killed.”

Lewis withdrew deeper into religion. At 15, he took to the pulpit in Baptist churches in and around his hometown, and gained a bit of fame in the pages of the Montgomery Advertiser as the “Boy Preacher from Troy.” By chance, he also acquired his first hero, Martin Luther King Jr. King was an unknown Montgomery minister when Lewis heard him deliver a Sunday sermon over a soul-music station. Riveted by King’s elegant delivery and his social-gospel message, Lewis decided to pattern himself on the man as much as possible, turning his sermons into attacks on segregation.

Too poor to attend King’s alma mater, Morehouse College in Atlanta, Lewis enrolled at the affordable American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville in 1957, but then decided to try and break the color bar at Troy State College back home. Screwing up his courage, he wrote to King for help, and wound up meeting with him and winning a promise of legal assistance. The effort ended abruptly when Lewis’s parents, fearing white reprisals, refused to go along and told him to be more cautious. But after he returned to Nashville, Lewis began attending a series of student workshops, run by the black pacifist theologian James Lawson of Vanderbilt, to study the works of Gandhi and Thoreau and to help plot a sit-in campaign aimed at the city’s eating places.

In February 1960, galvanized by the famous Woolworth’s sit-in at Greensboro, North Carolina, the newly formed Nashville Student Movement sprang into action. Lewis’s first arrest came on February 27; he was arrested three more times over the next six weeks and became known to local officials as a student ringleader; and in April, he attended SNCC’s founding conference in Raleigh. One of the fundamentals of the pacifist radicalism he had learned from Lawson was the Gandhian doctrine of Satyagraha (literally, “truth-force”). It was one’s duty, the doctrine ran, to openly violate unjust laws, and then to accept punishment, violent or not, in order to persuade oppressive authorities that violence was useless. SNCC’s early recruits tried as best they could to put this daunting idea into practice.

Between 1961 and 1963, while Martin Luther King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) captured national headlines, SNCC’s satyagrahi undertook black voter registration drives in violent Southern backwaters where no other civil rights organizations dared to tread. Lewis added to his own reputation for bravery when, after being invited to join the Congress of Racial Equality’s (CORE) Freedom Ride bus demonstration, in May 1961, he led the group into its first affray, entering the “Whites Only” waiting room in the Rock Hill, South Carolina, bus terminal and getting knocked down and bloodied by a band of local toughs. Later, when attacks on the riders in Alabama persuaded CORE that to continue the demonstration would be suicidal, Lewis, along with some of his Nashville friends, carried on, only to get beaten again, even more severely, by a club-wielding mob at the Montgomery bus station. Lewis and the replacement riders finally ended the demonstration by getting arrested in Jackson, Mississippi, from whence they were sent for thirty days to the notorious Parchman Prison Farm.

Shortly after Lewis and the others departed Parchman in early September, the Interstate Commerce Commission issued a directive desegregating Southern busline facilities. Lewis quietly returned to his nonviolent protests and organizing work for SNCC. Two years later, having virtually desegregated downtown Nashville, he was named SNCC’s national chairman. And two months after that, on August 28, 1963, Lewis stood uneasily on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, preparing to address 200,000 people.

Lewis’s appearance at the March on Washington thrust him forward as the tribune of SNCC’s growing militance. The march’s organizers, the elder statesman A. Philip Randolph and his much younger protege, Bayard Rustin, had hoped to use the occasion to pressure Congress into enacting pending civil rights legislation, and they wanted no hint of confrontation. But Lewis and his SNCC comrades, weary of living in perpetual dread of Klansmen and backwoods sheriffs and with no helpful federal response, drafted an angry declamation. They grudgingly toned it down at the last minute, at Randolph’s request. Still, compared to King’s “I Have a Dream” oration later that day, Lewis’s speech—which criticized the Kennedy liberals, demanded massive help for the poor and called for a nonviolent social revolution—was incendiary, less a sermon on brotherhood than a call to resistance.

The speech made Lewis famous as the civil rights movement’s enfant terrible. But, as movement insiders understood, Lewis’s hotspur image was misleading. The mainstream civil rights leaders had always found him easier to work with than anyone else in SNCC. “His purity,” Mary King later wrote, “made him appear more militant politically than he actually was.”

In the summer of 1964, SNCC and CORE recruited hundreds of Northern white college students to help register black voters in the state that everyone acknowledged was segregation’s strongest bulwark. “If we can crack Mississippi, we will likely be able to crack the system in the rest of the country,” Lewis told a reporter as the project began. But Mississippi did not crack, at least not right away, and after months of futile toil amid constant terror, punctuated by the murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, SNCC was gripped by a growing pessimism about the movement’s basic principles. Some field organizers began to regard nonviolence not as a way of life but as an outmoded tactic. (Soon they would be surreptitiously packing firearms.) Many more SNCC volunteers, embittered by Northern liberal temporizing and by the obduracy of Southern racism, reassessed the virtues of racial integration and concluded that blacks had to organize on their own.

Lewis felt the shift in attitude, sympathized with aspects of it and tried to carve out a middle position. Late in 1964, he fortuitously encountered Malcolm X in Nairobi at the tail end of an official SNCC fact-finding trip to Africa (Malcolm was returning home from his famous journey to Mecca); and, after two days of intense conversation, he came away impressed with Malcolm’s repeated renunciations of his earlier racial separatism. In February 1965, Lewis told a SNCC staff meeting that their primary purpose had to be “the liberation of black people,” that white liberals and affluent blacks could not be counted on for support, and that both SNCC and the civil rights movement at large had to be “black-controlled, dominated, and led.” But he rejected any suggestion that nonviolence be abandoned, or that sincere white supporters be spurned.

The Selma campaign in the winter and spring of 1965 brought still more intramural issues to a head. SNCC had been trying to register black voters in the city for two years, with meager results. Only when King and the SCLC arrived on the scene, late in 1964, did the national media begin paying attention, which outraged SNCC volunteers, who were fed up with seeing King—”De Lawd,” they called him—get all the credit for their hard work. Unable to persuade SNCC to endorse King’s operation, Lewis agreed, on his own, to join an SCLC march from Selma to Montgomery on March 7.

Walking at the head of the column beside Hosea Williams, carrying a knapsack containing a toothbrush, toothpaste, some fruit and two books (Richard Hofstadter’s The American Political Tradition and a volume by Thomas Merton), Lewis reached the apex of the humpbacked Edmund Pettus Bridge leading out of town, and saw before him a sea of blue: upwards of 200 Alabama state troopers, sheriff’s deputies and posse members on horseback brandishing bull whips, cattle prods and batons wrapped in barbed wire. The marchers knelt and prayed. Within seconds, tear gas was billowing over them, and the posse was trampling the fallen front lines, smashing limbs and splattering blood all the way back to town. Lewis lay on the ground with a fractured skull and a concussion. (“I saw death,” he later remarked.) That night, the nation, including President Lyndon Johnson, watched film of the beatings on television.

The Selma incident jolted Johnson and Congress into passing the Voting Rights Act later that year. Lewis was hailed louder than ever as a national hero. But, inside of his own organization, his position was tenuous. James Forman, SNCC’s longtime executive secretary, latched on to the new mood and began regarding Lewis as an expendable patsy. One of the most talented of the new organizers, Stokely Carmichael from Howard University, became the favorite of those who thought Lewis should be replaced. “If you took a clear look at John Lewis, he looked more like a young Martin Luther King Jr. than anything else,” recalled Carmichael, now known as Kwame Toure. “Our direction was clear, with a heavy emphasis on nationalism. And strong, as strong as Malcolm had it, as strong as we could get it.” Push came to shove at a SNCC leadership gathering in May 1966. Lewis resigned from SNCC soon after, and, under Carmichael and H. Rap Brown, the organization slid toward black-power extremism. Lewis landed a job with the liberal Field Foundation in New York. Increasingly depressed, a small-town Southerner cut loose in Manhattan, he holed up nights in his Chelsea apartment, drinking six-packs of Rheingold beer and reading long letters from his friend Julian Bond, who had won election to the Georgia legislature and had also quit SNCC.

In March 1968, Robert Kennedy announced his presidential candidacy. Lewis immediately volunteered and was sent to work on organizing the Indiana primary campaign, his first direct involvement in mainstream electoral politics. Shortly past sundown on April 4, 1968, while awaiting Kennedy’s arrival at an outdoor rally in the middle of the Indianapolis ghetto, Lewis received word that King had been shot in Memphis. Turning up late, and without his usual police escort (which had refused to enter the neighborhood), Kennedy, stricken, clambered atop a flatbed truck and improvised what many consider the greatest speech of his life, quoting Aeschylus from memory to his grief-stricken black listeners, remarking that his brother had also been killed by a white man, pleading for calm and racial harmony. Two months later, Lewis was part of the select gaggle of friends and campaign staff who assembled in Kennedy’s hotel suite in Los Angeles to celebrate the candidate’s victory in the California primary. The two men bantered awhile, until Kennedy abruptly withdrew, saying that he had to give his acceptance speech in the ballroom below. Kennedy told Lewis to stick around; he would be right back.

After 1968, with King and Kennedy dead and with Richard Nixon in the White House, Lewis watched black protest politics go haywire. “You put on a dashiki, you let your hair grow long and you get an Afro, okay,” Lewis later remarked, “but you’re not doing anything to change the lives and conditions of poor people.” While a few young movement veterans, notably King’s former aide Andrew Young, entered electoral politics, Lewis, not yet fully recovered from his ouster from SNCC, struggled back to his feet.

He found a suitable niche at the Southern Regional Council’s Voter Education Project, where for seven years he oversaw the registration of tens of thousands of Southern blacks, including his mother, under the Voting Rights Act. In 1976, after Jimmy Carter’s election, the political tide briefly shifted. Carter plucked Andrew Young out of the Congress to become his ambassador to the United Nations, and Lewis ran for Young’s Atlanta seat, finishing a respectable second to a popular white liberal, Wyche Fowler. Carter immediately appointed Lewis associate director of ACTION, where he worked on federally funded community organizing efforts. In 1980, he quit, and a year later won election to the Atlanta City Council.

In 1986, when the congressional seat for Atlanta once again fell vacant, Lewis decided to run. But then, coming out of nowhere, Julian Bond entered the race as the darling of Atlanta’s black elite. Bond had movie-star looks and a silver tongue, backed up with plenty of money and endorsements from big-time Democrats, including Ed Koch and Edward Kennedy. Although local civil rights veterans were badly torn, most of them wound up supporting Bond, including (privately) Andrew Young, who was by this time Atlanta’s mayor. Given that there was little difference between Bond and Lewis on the issues, Bond should have won easily, and he nearly did, polling almost half the votes in a five-way preliminary primary. But, having failed to gain a clear majority, Bond had to face Lewis in a run-off. And Lewis, having learned some lessons from 1966, decided to play political hardball.

Lewis’s strategy centered on making a virtue of his plainness, conjuring up a clash of styles that dated back to the ‘60s. Although both men had been SNCC heroes, Bond had been the charming press secretary, working safely behind the battlelines at the group’s Atlanta headquarters, telling SNCC’s story to Northern reporters—while Lewis actually was the story, risking life and limb. Since then, Lewis had remained the sturdy, hardworking man of the people, while Bond, although active in the Georgia legislature, found time to revel in the celebrity limelight—a snappy dresser and jetsetter who turned up regularly on national TV, including a host appearance on “Saturday Night Live.” “Vote for the tugboat, not the showboat,” was one of Lewis’s campaign mottoes, and the theme began attracting two key constituencies: working-class blacks, who felt neglected by the city’s well-connected black leaders, and more moderate and conservative whites, who breathed easier voting for the homely John Lewis than for the glitzy Julian Bond.

Lewis narrowly won the election, but he lost an old and dear friend, a kindred spirit in the larger political scheme of things. It would be several years before the two men patched things up.

A decade later, Lewis has solidified his base in Atlanta; and in its own modest way, his local rainbow coalition has proven far sturdier than Jackson’s failed national effort. But in general, American politics, and especially Southern politics, are even more racially divided today than in 1986. There are more blacks than ever in Congress, but most of the newcomers owe their success to court-ordered racial gerrymandering, which has made interracial coalition-building more difficult. Thirty years after the Selma march, the South has reverted to a region of two racial parties, with the conservative white party—formerly the Democrats, now the Republicans—once again in the ascendancy. Nationwide, Republican leaders, having reaped the long-term electoral advantages of Richard Nixon’s old Southern strategy, make half-hearted noises about reaching out for black support, while the Democrats dither about how they can regain moderate white voters without endangering their black base. Into the vacuum have stepped figures like Farrakhan.

In the face of all this, Lewis upholds what he sees as the true legacy of 1968: “When Dr. King organized the Poor People’s campaign, he said that the next great movement in America must not be a civil rights movement per se, but it must be a movement of those who have been left out and left behind,” Lewis told me recently. “You’re talking about class. Maybe I’m treading into some dangerous areas, but I don’t see any more significant or great victories in terms of race. The beloved community, if we get there, it will not be traveling down a racial path.” Lewis insists that he sees early signs of an interracial liberal renewal. “I think we’re at the beginning of something,” he said in his office, encircled by his photographs of protests past. “We’re on the edge, or maybe it’s the advent, or something. I can feel it as I move around. But individuals must come forward with a sense of vision.”

That was Lewis’s mystical side talking, and on first hearing it all sounded far-fetched. Given the failure of President Clinton’s health-care initiative, given the anti-government mood that cuts across the political spectrum, the prospects for any grand liberal departure seem quite distant. Likewise, although the separatist impulse in black politics may, as Lewis suspects, have largely run its course, that is no guarantee that Lewis’s more generous, optimistic, integrationist vision, rooted in the ‘60s and the Southern black church, can soon replace it, especially among poor younger blacks in the larger metropolitan areas.

Nor do the prevailing liberal orthodoxies on race and related matters offer much assurance that Lewis’s predictions will come true. Since the ‘60s, American liberals have generally found themselves tangled up in a false dichotomy, favoring government intervention to alleviate social and economic inequality, while disparaging calls for widened private opportunity and individual self-improvement as reversions to callous, dog-eat-dog, laissez-faire capitalism. And after the ‘60s, American liberalism became closely identified with race-based formulas for social and political justice, above all affirmative action and electoral gerrymandering—formulas which, even with all of their obvious benefits in bringing millions of the once-excluded into the mainstream of American life, have paradoxically undermined the building of sturdy interracial coalitions.

If Lewis’s projected liberal revival is to succeed, he and others will have to shake up these liberal orthodoxies. More than many liberal Democrats, he is forthright about the necessity of encouraging private enterprise, investment and moral uplift among the down-and-out, pursued in creative tension with the more familiar government-sponsored programs to provide the disadvantaged with better jobs and schools and housing. Although Lewis stoutly defends the principles of affirmative action and race-based districting, he is also aware of their limitations and possible abuses. With respect to affirmative action, he is sympathetic to the idea of eventually gearing programs to class and not strictly to race, in part to prevent affluent individuals from gaining advantages solely because they happen to be black. On electoral districting, he would like to see racial guidelines altered so that “black” districts would be less solidly black—giving black candidates a fair shot at winning elections, but only if they reach out for white support (and, as a corollary, compelling candidates in “white” districts to gain minority support).

In short, although Lewis has managed to find ways to merge the past and the present, the ‘60s and the ‘90s, inside the House Democratic caucus he and his allies will have a much tougher time doing so in the nation at large. Still, what is remarkable about John Lewis is that he is in a powerful position to try. If the Democrats recapture the House this November, the new majority leadership is bound to be much more aggressive than during the Foley era—and Lewis, his stature enhanced by his contributions over the past two years, will be in the thick of things more than ever. Even if the Democrats fail, Lewis will remain near the pinnacle of his party’s leadership—the only African American in the leadership of either party of either house. Whatever the electoral outcome this fall, he will have finally regained the national stage that he last occupied a third of a century ago, when as a mystical 23-year-old firebrand he scared the living daylights out of people at the March on Washington. And he will do so having learned the hard way about the rougher imperatives of political life.

When last we met, back in May—exactly thirty years after his ouster as SNCC’s chairman—Lewis was in high spirits, and he tried to explain what was the same and what was different for him. He mentioned his abiding belief in marking off and sticking to immutable principles; he also spoke of how, as an elected politician and no longer simply a movement politician, he had to know when to cut a deal, to stick it to his opponents, to be practical. “I like winning,” he suddenly interjected, breaking into a mischievous smile. “I like winning, I really do. I don’t like to lose.”