That Twitter was caught flat-footed by the unprecedented security breach that occurred on Wednesday evening, in which a number of prominent accounts—including those of Joe Biden, Kanye West, and Elon Musk—were hacked as a part of a Bitcoin scam was not, in itself, surprising. Despite leapfrogging from scandal to scandal, the social media company has never shown itself to be particularly adept at crisis management; the seeds of this particular failure appeared years ago. But the incident was nevertheless unnerving in that it revealed the internet’s fragility and how much power is concentrated in a few companies that are effectively monopolies. Though Twitter took action on Wednesday by blocking verified users from tweeting, it disclosed very little about what was actually going on.

We know a little bit more about what happened now, the day after. The Twitter accounts were taken over using “internal systems and tools,” according to a company statement. Vice reported that a “Twitter insider was responsible” for giving hackers access to those tools. If indeed this was an inside job, it would be the second at the company in the past few years; the first involved an employee leaking information to Saudi intelligence. However it happened, hackers were able to access many of the platform’s most prominent accounts and tweet a solicitation: “Everyone is asking me to give back and now is the time,” the tweets read. They then promised to double money sent to a Bitcoin address. It was a rudimentary con, but it worked: One analysis showed that 400 payments totaling over $120,000 were sent to that wallet. (It’s possible some of this money was sent by the scammers themselves.)

The security breach may have been limited to that Bitcoin haul, which would be something of a best-case scenario, both for Twitter and its users. It’s also possible, however, that the hackers were also after other valuable loot, namely the contents of Twitter’s unencrytped direct messages. While the platform shut down tweets from verified users fairly quickly, it did not appear to do anything to secure this part of its service. In a statement, Republican Senator Josh Hawley (a frequent critic of tech companies) raised this possibility, warning, “As you know, millions of your users rely on your service not just to tweet publicly but also to communicate privately through your direct message service. A successful attack on your system’s servers represents a threat to all of your users’ privacy and data security.”

Even though the scope of this attack is still not known, it reveals a great deal about Twitter’s profound potential to rapidly destabilize the real world. As The Verge’s Casey Newton wrote shortly after the attack, “The threat here is not simply user privacy and data security, though those threats are real and substantial. It is about the striking potential of Twitter to incite real-world chaos through impersonation and fraud.”

The 2016 election was shaken by fraud and disinformation; this scheme may serve as a prelude to several months of unsettling breaches. Twitter is still ill-equipped to handle hacks, data breaches, and other chicanery, whether perpetrated by individuals, groups, or governments. Given the increasing centralization of the internet, moreover, platforms like Twitter have a profound effect on how people communicate and stay informed—though Twitter’s user base is small relative to other major social media services’, it includes a disproportionate number of politicians, celebrities, and journalists. Wednesday’s hack underlines Twitter’s centrality to news—and to emergency alerts—but also its fundamental shortcomings, particularly when dealing with hostile actors. The platform that millions rely on to stay informed and up-to-date remains profoundly susceptible to destabilization, whether out of mischief or maliciousness.

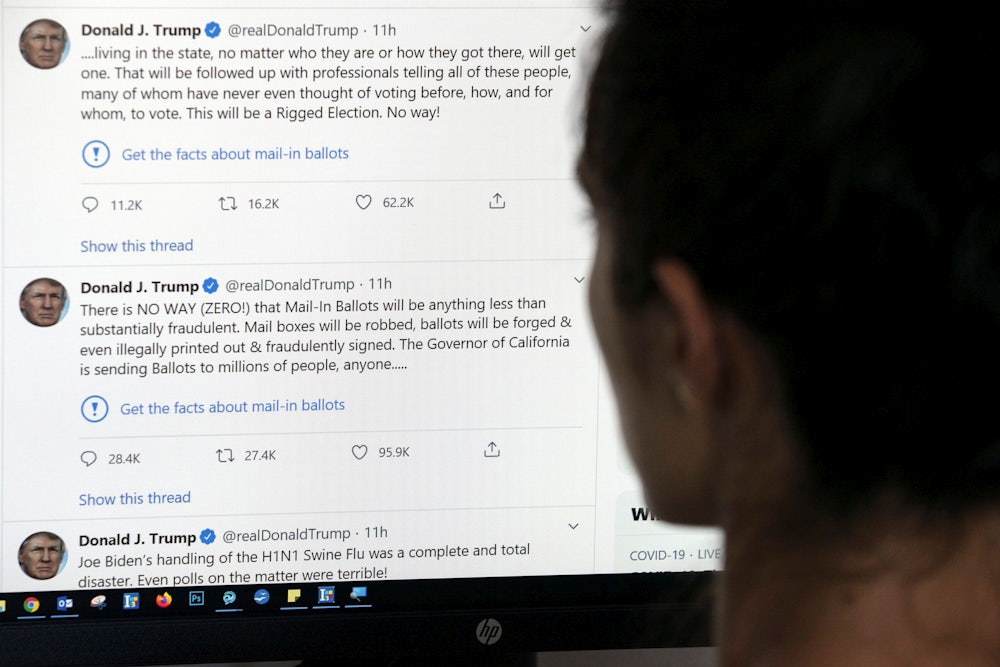

Today, it might just be a Bitcoin scam. But what if hackers are motivated not by a desire for quick cash but by a plan to destabilize a political campaign or embark on a serious blackmail operation? Given Donald Trump’s propensity for using his account to conduct foreign policy, one does not have to stretch to see such a breach whose goal was to foment armed conflict.

But there was another unexpected consequence of Twitter’s ham-fisted response to the breach: The platform was, for the first time in years, fun again. With verified accounts blocked from posting, some of the weird anarchic energy of Old Twitter seeped in. “Suddenly, many a Twitter blowhard was locked out; the drivers of conversation were muzzled, and the plebes had the controls. Nature was healing,” wrote Wired’s Angela Watercutter. For a little more than an hour, we didn’t have to worry about seeing a tweet from the president—although he still managed to retweet a couple of times.

But this points back to the larger problem. Twitter is not secure, and it’s not adept at dealing with crises. It has the same problems it had five years ago, except many of those problems have gotten worse. At the same time, it’s also not really enjoyable to spend time on—or, at the very least, a lot less so than it was a few years ago. Everything, it seems, would be a little bit better if it were to just go away. We all hate Twitter, both the social media network and the manifestly incompetent company that runs it. If only we didn’t seem to need it so much.