Support from the White House is one of the last things President Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil has going for him, politically. His administration’s dismissive and callous response to the Covid-19 pandemic is among the worst in the world. After presiding over a drastic spike in deforestation the last two years, his administration was forced this month by divestment threats from 32 international financial institutions to issue a 120-day ban on any fires in the Amazon rain forest. Meanwhile, fading political support has driven the president to negotiate with the political parties and corrupt powerbrokers he once categorically rejected. Impeachment—the fate of Dilma Rousseff and a fleeting possibility with Bolsonaro’s immediate predecessor, Michel Temer—has once again entered the national conversation. And Bolsonaro recently tested positive for the coronavirus he has so frequently belittled.

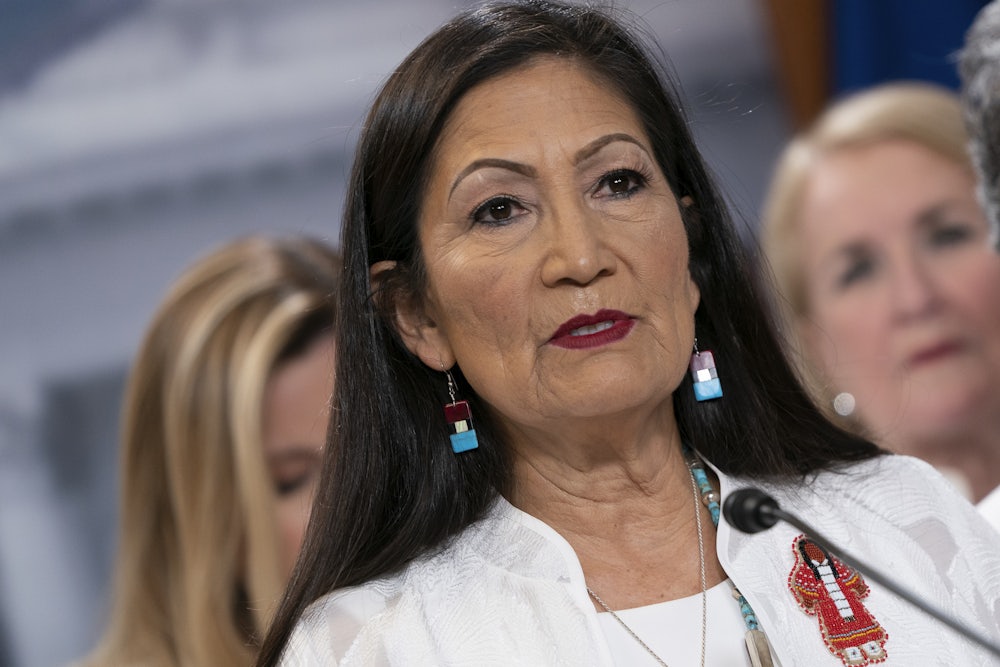

Congresswoman Deb Haaland, a Democrat from New Mexico, is working on something in the House of Representatives that could further undermine Bolsonaro’s administration in particularly embarrassing fashion. Last July, the White House designated Brazil as a major non-NATO ally, a category that includes South Korea, Australia, Argentina, and Kuwait. The designation makes it much easier for Brazil to purchase U.S. weapons and defense equipment. It’s precisely the sort of international recognition that Brazil craves and one of the few accomplishments the Bolsonaro administration can point to in international affairs. Earlier this week, however, the Brazilian press reported that Haaland is preparing a floor amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act that would revoke Brazil’s designation as a major non-NATO ally. While the matter has received relatively little attention in the United States, the implications for both Brazil and the global carbon sink it contains could be huge.

In the time since she assumed office—only days after Bolsonaro’s inauguration—Haaland has emerged as perhaps the most persistent American governmental thorn in the side of the Bolsonaro administration. As one of the first two Native American women in Congress, Haaland has consistently emphasized the intrinsic link between protecting indigenous rights and climate justice—not just on a national but on a global level. Last March, Haaland argued in a Washington Post op-ed with Joênia Wapichana, the first indigenous Brazilian woman elected to her country’s national Congress, that both Bolsonaro and Trump were threatening the environment through their encroachments on indigenous rights: “The regressions undertaken by the Trump and Bolsonaro governments are overwhelming and underscore the need for solidarity between indigenous peoples and our allies in North and South America.”

When I reached out to her office about the amendment being reported in the Brazilian press, Haaland pointed to the Bolsonaro administration’s dismissal of the coronavirus threat. “Even after being diagnosed with Covid-19, Bolsonaro fails to take this virus seriously and is directly targeting vulnerable indigenous communities by failing to provide them with adequate funding to address this pandemic. It’s an attack on human rights,” the congresswoman told me via email. “The United States should not align itself with a leader who time and again puts his people at risk, destroys the environment, and violates human rights.”

Were the amendment to pass, it could prove game-changing in Brazilian politics. Among other possible effects, it could, like the divestment campaign, curb Bolsonaro’s more destructive tendencies—with tremendous repercussions for the Amazon and its inhabitants, who have been a particular target of the Bolsonaro administration and its rapacious approach to development. But even though the amendment is unlikely to become official policy, it may still have an effect. The proposal represents a frontal assault on one of the vanishingly few diplomatic coups the Bolsonaro government has managed to produce. It is thus tangible evidence Brazilian progressives can point to when asserting that Bolsonaro’s anti-democratic tendencies are not producing lasting results. If voters can be persuaded that Bolsonaro’s approach to the environment and minorities is actually holding the country back, his political prospects will falter.

Haaland’s move also carries wider implications. If Joe Biden wins the presidency this November—an increasingly likely scenario that would be devastating for Bolsonaro—Haaland’s work could and should become a model for a progressive U.S. approach to elected far-right politicians abroad. While there are good reasons for the U.S. not to intervene in the politics of sovereign democratic states, it can foster meaningful ties of solidarity and support for the downtrodden and marginalized while opposing the momentum of authoritarian movements.

Focusing on people is key to the success of this approach. When French President Emmanuel Macron suggested that international action could be triggered in the Amazon “if a sovereign state took obvious and concrete measures which were clearly against the interest of the planet,” he inadvertently lent credence to right-wing Brazilian conspiracy theories about foreign encroachment on Brazilian territory. This allowed Bolsonaro to mobilize an aggrieved nationalism that is to his political advantage. Haaland, in contrast, has built personal connections to individual leaders and movements on the front lines of the struggle against environmental depredation.

Bolsonaro’s dismal environmental record is tied inextricably to his indifference to the fate of indigenous peoples. Years before he emerged as a serious presidential contender, Bolsonaro argued that stringent legal protections for the environment and indigenous people were holding the country back in its efforts to achieve the status of global power. Bringing this connection up in a debate over the defense budget is also a reminder of the militarized nature of previous violence against Brazil’s indigenous people, their lives and livelihoods often being sacrificed in the name of economic progress. This was particularly true during the military dictatorship that ruled the country for 21 years, when Amazon development, including highway construction and mining projects, devastated indigenous communities. (Unsurprisingly, Bolsonaro first made a political name for himself as an unapologetic defender of the 1964–1985 military regime.)

Haaland’s latest measure is set to bring together various concerns that international observers have articulated since Bolsonaro’s election, namely his anti-democratic tendencies, his militarism, his anti-environmentalism, and his hostility to native peoples. Ahead of his reelection campaign in 2022, these sorts of measures will make it harder for Bolsonaro to claim that his approach has worked to bolster Brazil’s international standing and future prospects. A potential Biden administration would do well to build on Haaland’s initiatives if it is serious about advancing a boldly progressive foreign policy—not to mention avoiding global environmental catastrophe.

Haaland is a particularly dogged opponent of the Bolsonaro administration, but she is not alone among U.S. policymakers. Last September, Arizona Democratic Representative Raul Grijalva of Arizona introduced a lengthy resolution delineating various concerns over Bolsonaro’s policies. The measure was backed by Haaland, Ro Khanna of California, and 12 co-sponsors. This is a relatively small caucus focused on what is happening in Latin America’s largest and most influential country, but their influence is real. Haaland was a co-chair of Senator Elizabeth Warren’s presidential campaign, and Khanna served in the same capacity for Senator Bernie Sanders. So it’s easy to imagine that such voices might help drive a progressive new foreign policy under a Democratic administration.

These kinds of efforts come not a moment too soon. As the renowned climate scientists Thomas E. Lovejoy and Carlos Nobre put it last December in Science Advances, “[D]ry seasons in Amazonian regions are already hotter and longer. Mortality rates of wet climate species are increased, whereas dry climate species are showing resilience. The increasing frequency of unprecedented droughts in 2005, 2010, and 2015/16 is signaling that the tipping point is at hand. Bluntly put, the Amazon not only cannot withstand further deforestation but also now requires rebuilding as the underpinning base of the hydrological cycle if the Amazon is to continue to serve as a flywheel of continental climate for the planet and an essential part of the global carbon cycle as it has for millennia.”

Indigenous livelihoods won’t recover if policies do not change soon, and the mass die-off that continued Amazon deforestation could trigger would release billions of tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Given those stakes, maybe a few more people with the power to shape policy could stand to back Deb Haaland and, regardless of the fate of the amendment, give Bolsonaro’s opponents some ammunition. Even as much of the world shelters in place or struggles to reopen amid the pandemic’s disruption, the crisis in Brazil continues.