On Monday, the Washington NFL team announced that it will officially retire and replace its name, a slur originally used to encourage the murder of Native people. The announcement raises many questions regarding what comes next as it relates to both the franchise nickname and the remainder of professional and amateur sports teams still using and capitalizing from pan-Indian imagery. But it also raises another question—about land.

The Washington franchise currently plays its home games at FedEx Field in Landover, Maryland. The team moved to Maryland in 1997 after playing for 35 years in the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium, which is located directly west of the Anacostia River, near the Hill East and Kingman Park neighborhoods in the heart of D.C. But the land is technically not D.C.’s. The plot that stadium still sits on is owned by the National Park Service and is currently leased to the Washington, D.C., government through 2038.

For years, D.C. politicians and community members have called for Congress to pass ownership of the land to D.C.’s government. In a Washington Post column published last November, D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser joined four of her predecessors in arguing that the current lease is too restrictive, as it prevents long-term planning for the location, which they described as currently being little more than “190 acres of mostly asphalt.” Groups like Fair Budget Coalition and EngageDC have recently pushed Bowser to invest funding in housing for low-income Black D.C. residents in light of the pandemic, while everyone from district council members to Georgetown students have admitted that the RFK campus would be a prime location for affordable housing. As of now, the old stadium is slated to be demolished next year—it’s what comes after that demolition, when the Washington NFL team begins shopping around for a new home stadium, that should have the people of D.C. paying close attention to the franchise’s long-overdue change of heart.

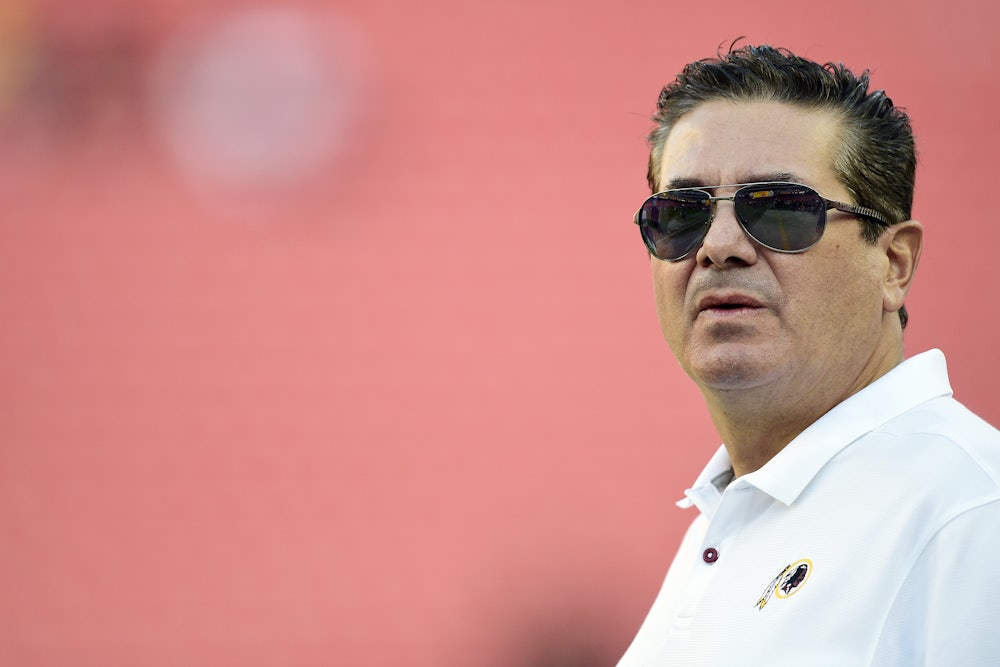

The decision by team owner Daniel Snyder to change the team name appeared from the outside to be heavily influenced by the financial ramifications that awaited him if he chose again to cling to the racial slur. Multiple financial partners, recognizing which way the wind was blowing following the uprisings that sprawled out from the police killing of George Floyd, informed Snyder that they would not maintain their business relationships with the franchise if the slur remained. Money tends to be persuasive that way, so he quickly did away with it. His reward, in this case, is that he gets to keep the millions of dollars he already reaps from licensing and naming-rights deals with Amazon and Nike and FedEx and add to that pile of money whenever the franchise unveils its new line of jerseys, T-shirts, and hats. This is already too good an outcome for someone like Snyder.

Ever since the franchise left D.C. proper, there have been repeated calls by the city’s mayors, council members, and fans for the team to return. For the past decade, one of the major obstacles to this return has been the team name. As it became a hot-button political topic for D.C.’s leaders, pressure built by a campaign sustained by Native communities and groups led many leaders, including the current mayor’s office, to officially oppose any return to D.C. as long as the R-word remained. It also became a political issue, as both local and federal legislators, like Representative Raul Grijalva, who currently chairs the congressional committee that determines what National Park Service lands can be used for, opposed a return with the name intact. Just two weeks ago, D.C. Deputy Mayor John Falcicchio told the Post, “There is no viable path, locally or federally, for the Washington football team to return to Washington, D.C., without first changing the team name.”

With the slur retired and a new name pending, the door, at least politically speaking, could be opened for the franchise’s return to D.C. But that would just be swapping one injustice for another. Despite the now-widespread knowledge that publicly financed stadiums are a poor public investment, the stadium grift—in which billionaire team owners convince city councils to hold their constituents hostage as they foot the bill for a multimillion-dollar stadium—is real. Professional sports team owners everywhere continue to raid public money for all they can get their hands on, for the simple reason that local officials are easy to convince with the flash of some cash. This has often resulted in budget shortfalls, as was the case in Cobb County, Georgia, where the Atlanta Braves (another franchise in need of a mascot retirement) fleeced the county to the tune of $400 million and forced the local library system to scale down.

Given the precarious situation facing tens of thousands of D.C. residents, the city cannot afford to let that 190 acres of asphalt fall back into the hands of a particularly craven billionaire. In normal times, the demand for affordable housing anywhere in the United States, especially in high-density urban areas like D.C., was already soaring. Now, with the coronavirus and the government’s continued failed response to the pandemic having already forced millions out of work and further into financial instability, affordable housing projects are no longer an option but a necessity.

Last year, Bowser pledged to increase funding for affordable housing, even pointing to the RFK site in the November op-ed as a prime location for “thousands of new homes.” But due to current restrictions spurred by the pandemic, funding to crucial programs like the Housing Production Trust Fund, which in part supports the program that helps tenants move toward purchasing property when an owner goes to sell, is reportedly going to be cut under the upcoming budget.

With any luck, D.C. will invest not in the bank account of Snyder but in itself and its community members. Vincent Gray, one of the former mayors who helped pen the November op-ed and the current council member for Ward 7, was supportive of the team’s return to a D.C.-owned RFK campus in 2013. But when he spoke on The Kojo Nnamdi Show last week, he appeared to have moved on from that dream, saying, “I think that train has left the station.”

Gray and the contingent of mayors noted toward the end of their Post op-ed that any discussions of including a new stadium in the RFK campus plans would be “a debate for a future date and … something we should decide by and for ourselves.” And that is undeniably fair. What happens to the RFK campus should be up to the people of D.C., especially those of the bordering neighborhoods who would be directly impacted. Snyder and his team already spent two decades embarrassing the city. There’s no need to hand him an extra bag of free money for doing the absolute minimum after years of fighting it.