There was something of a twist in last week’s monthly jobs report: In May, the unemployment rate in the United States had seemingly declined by a few percentage points, hinting at the start of an economic recovery. The president was overjoyed by the news. “A rocket ship,” he called the purported rebound. Following his administration’s disastrous response to the coronavirus and his threats to quash ongoing protests over police brutality through military force, Trump’s best hope of reelection this fall is, talking heads have agreed, a swift economic recovery. But since the release of the May report, some economists have warned that the uptick in jobs could have been misleading or incorrect. And in any case, more than 20 million workers remain unemployed. The rocket ship, so to speak, is probably due for a crash-landing.

As the financial press has noted, though the stock market has fluctuated wildly over the last few months, it’s also proven more than adept at resurrecting itself. Unfortunately, the well-being of Wall Street and the stock market has no relationship whatsoever to the well-being of the majority of American workers. (How else could you explain markets surging while the nation reels from mass unemployment and widespread unrest over police violence?) On Wednesday, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development called the current downturn the worst recession in a century and warned that the economy could further plummet following a second outbreak of the coronavirus, which incidentally seems to be in the making after the reopening of several states against public health officials’ warnings and a rash of Memorial Day gatherings.

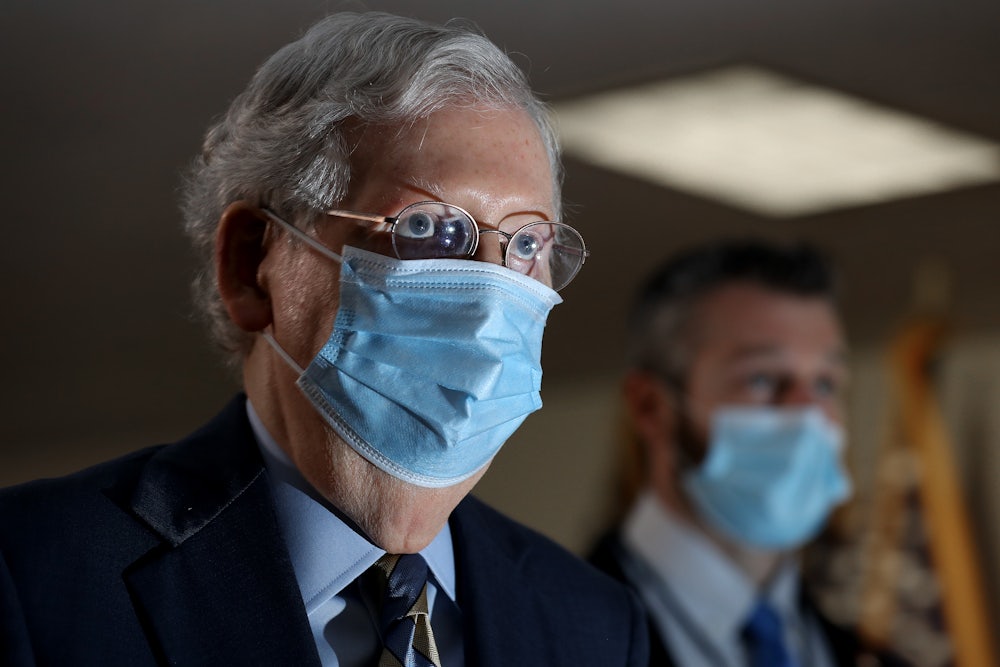

Though we’re in the midst of an essentially unprecedented economic crisis, and almost certainly in for a very long stretch of hardship, calls for budget-tightening have reliably restarted. Austerity is the hammer that thinks everything is a nail, as it were. Republicans continue to oppose a new stimulus bill even as food banks remain overwhelmed by demand and nearly half of Americans have lost income as a result of the coronavirus. The numbers in the May jobs report, shaky as they were, have only given them additional fodder to further delay a vote on a new relief package. “The economic fallout from this pandemic may have bottomed out and begun to turn around weeks earlier than had been predicted,” Mitch McConnell said earlier this week. “Our citizens are getting their jobs back by the millions.” The 30 million people still out of work probably don’t take much comfort in that assessment, but Senate Republicans have vowed not to entertain any further stimulus proposals until July, which conveniently includes a two-week recess right before pandemic unemployment benefits are set to expire.

That’s perhaps not much of a surprise from the party that fretted over laid-off poverty-wage workers receiving slightly more in unemployment benefits than they made while working. But as is usually the case, a certain amount of budget hand-wringing has also started up in ostensibly more liberal corners. This week, The New York Times editorial board issued a caution to Mayor Bill de Blasio against borrowing money to cover the city’s funding shortfalls. Though its proposal identified some legitimate areas of waste—cushy consulting contracts, unnecessary software licenses, sprawling NYPD overtime—it inevitably also landed on city workers’ benefits as a site of possible belt-tightening. “If the fiscal crisis is serious enough to consider assuming billions in debt, it is serious enough to ask the unions to come back to the negotiating table,” the board wrote. “Among the issues to discuss: the city’s exceedingly generous health care benefits.” That seems incendiary—if not a little homicidal—during the worst public health crisis in a generation.

Even if some kind of economic recovery is indeed underway, budget austerity in this moment—even the sort that seems measured, or nominally less malicious than Republican schemes—will only seed the ground for more wide-scale misery. On Wednesday, the Federal Reserve predicted a slow, years-long recovery and forecast that millions of the jobs lost during the pandemic could take years to return, or even vanish forever. It’s also worth recalling that while the recovery from the Great Recession officially began in 2009, it took more than a decade for household income and jobs to return to their pre-recession levels. Then there’s the question of what kind of work might come back, if and when it does. Right before the pandemic, during the same period that employment in the U.S. was at a record high, nearly half of all Americans were working low-wage jobs. The employment rate is one thing, in other words, but the number of jobs that pay a living wage is quite another.

All things considered, the official numbers that theoretically gauge the strength of the economy—including gross domestic product, the unemployment rate, and temporary on-paper increases in income—may increasingly obscure more than they reveal about the situation of the average worker. “The labor market has suffered a traumatic blow and a full recovery will be measured in years, not weeks or months,” economist Nancy Vanden Houten recently told Reuters. And of course, as unemployment remains high and state and city governments are strapped for funding as the result of lost tax revenue, billionaires, boosted by the climbing stock market, got richer for the sixth week in a row. Perhaps it’s finally time for an assessment of the economy that measures something other than their plunder.