Since the beginning of June, mass protests in over 750 towns and cities have decried the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis by police officer Derek Chauvin—and they have remade the possibilities for confronting police brutality in the United States. By mobilizing behind the slogan “Defund the Police,” the protests have compelled Americans to see beyond police reform to a radical reconceiving of public safety. This has already yielded commitments from municipal politicians—including most Minneapolis City Council members—to disband police departments and redistribute their budgets to housing, education, and health care. This is no small feat.

Despite the caveats and reservations among some politicians and media commentators about the utility of “Defund the Police,” the mantra speaks to the power of not only the thousands marching in the streets but the demand itself—which links dismantling the untenable status quo with a new reimagining of public spending.

In many ways, the activists making these demands echo the dreams of earlier generations confronting another devastating form of state violence: America’s post-1945 national security state. Since the 1950s, a diverse array of figures—economists, policymakers, anti-war activists, even defense workers—have aimed to transfer dollars away from “defense” to solve domestic problems of national magnitude, from poverty to transportation to climate change, in what they often called “conversion.” Like current activists seeking to defund the police, proponents of defense conversion confronted an intractable institution that thwarted democratic processes, suppressed political dissent, and bestowed financial prosperity on a few over the interests of the many.

There’s something to learn from this history amid national efforts to defund police departments, both in terms of the coalitions that got defense conversion onto the floors of Congress and, just as importantly, their failures to convert the warfare state to peaceful ends—which had consequences not only for America’s forever wars abroad but for the crime, drug, and domestic “terror” wars at home. As today’s activists move to reallocate city police budgets for social welfare ends, these efforts to abolish the military-industrial complex prove instructive.

The links between America’s policing practices, police departments’ primacy in municipal budgets, and the growth of the defense budget date to the Second World War. The conflict didn’t merely lay a foundation for the largest warfare state in humanity’s history; in the shadow of the Great Depression, wartime spending served as a “grand experiment” for John Maynard Keynes’s contention that government investment of any sort could boost employment, wages, and economic growth. While the war vindicated his theory, what form federal spending should take afterward remained unresolved.

But military spending became key to the expansion of the federal state with the outbreak of the Cold War in 1947. This was “military Keynesianism”: Exorbitant federal investment boosted incomes, smoothed the business cycle, stimulated regional development, and fostered dependent constituencies, from labor unions to “defense communities.” Of course, the products purchased in this investment devastated the global south and facilitated American interventionism. And as the historian Stuart Schrader has argued, the militarization of American foreign policy produced a feedback loop back home, as the lessons learned in counterinsurgent operations to subjugate colonized populations informed the modern methods of racialized policing in America’s cities.

Cold War anti-communism reinforced the justification for high military outlays and their benefits, and post–Korean War “peacetime” spending multiplied the missiles, fighter jets, and nuclear bombs, making the likelihood of nuclear extinction possible. There emerged a body of experts who questioned the necessity of this defense spending. The Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy emerged in 1957; it and similar groups were led by a cadre of scientists, activists, and academics to promote alternatives to nuclear buildups. The antinuclear movement provided the seedbed for defense conversion to germinate.

In the early 1960s, antinuclear reformers joined with public intellectuals, such as peace activist Kenneth E. Boulding and science writer Gerard Piel, to pen articles about how the military-industrial complex could be reoriented to serve human needs rather than war. But these dreams competed with political actors looking to trim down the national security state for less altruistic ends. Council of Economic Advisers chair Walter Heller wanted defense cuts to align with his proposed 1964 tax cuts, while Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara merely sought surgical budget cuts to achieve technocratic “efficiency” for a leaner but no less powerful military.

The disparate voices and events nonetheless produced a real moment for defense conversion in the early 1960s, one that forced defense-dependent labor unions to rethink their own ties to the warfare state. In 1964, the California state AFL-CIO laid out a template for “peacetime conversion,” with a national planning agency that would turn defense plants into rapid-transit and hydroelectric producers; it also proposed to replace military dollars with social welfare dollars in defense-dependent areas, including money for low-income housing, schools, community centers, and parks. This motivated South Dakota Senator George McGovern, long a critic of the nation’s arms race, to introduce a bill to establish a “National Economic Conversion Commission” that same year. “We have the opportunity now to apply a greater proportion of our national wealth and the talents of our people to solving some of the social and economic ills that still exist in this land of plenty,” he said. Despite the bill’s broad support, those seeking a leaner military rather than its transformation dominated the debate on the Senate floor. And escalation in Vietnam halted, at least temporarily, questions of conversion.

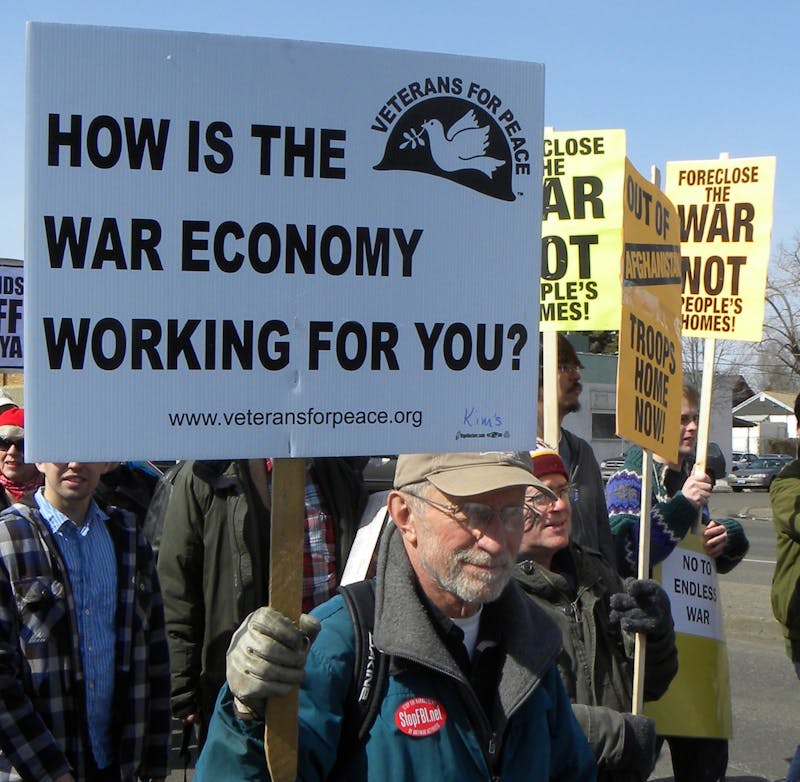

But the Vietnam War also democratized the possibilities for defense conversion. Mass deaths in Southeast Asia—of both Americans and Vietnamese—brought mass protests into American streets. These demanded not only an end to the war in Vietnam but a reimagining of American foreign policy that might hold political elites accountable for the quagmire and detach the country from the war economy. Anti-war liberals and leftists called out the “military-industrial-labor-complex” for its relentless hold over the political and economic “structure of our country.” Activists in Students for a Democratic Society targeted the draft because it sent Americans to die for an immoral war in Vietnam, but also because it recruited the working class for the war economy. At the same time, Marxist economists made popular arguments for defense conversion to be carried out through a project of socialism, arguing that only “the establishment of a socialist society can eliminate militarist priorities.”

The radical visions for defense conversion in the 1960s culminated with McGovern’s 1972 presidential campaign: He proposed a $30 billion cut to the defense budget and a revived plan for national defense conversion. McGovern’s defeat by Richard Nixon—along with rising inflation and unemployment—derailed conversion in Washington.

But Ronald Reagan’s revival of the arms race in the early 1980s mobilized Americans back into the streets: A multiracial, cross-class coalition of activists organized to eliminate nuclear weapons around such slogans as “Freeze Now, Then Reduce.” What began as a small effort of scientists to stop production of nuclear weapons turned into a “nuclear freeze movement” that reverberated in Washington, with Democrats in Congress proposing a “nuclear freeze resolution.” The freeze movement placed pressure on Reagan (and his Soviet counterpart, Mikhail Gorbachev) to reduce nuclear weapons in the name of peace, which seemed achievable on a large scale after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

The end of the Cold War provided a last chance for a significant “peace dividend.” With a creeping recession on the horizon, American activists, scholars, and politicians once again looked to the immediate stimulus potential of defense conversion. The moment appeared rife with opportunity, but hawkish Republicans and Democrats precluded the possibility: The Budget Enforcement Act of 1990 separated defense and domestic budgets to prevent military cutbacks from being reallocated to social programs. Bill Clinton continued this trend, eschewing defense conversion in response to arguments made by economic advisers like Robert Rubin that he should focus on deficit reduction. In this view, the finance sector would save the economy, and draining defense dollars would be unnecessary.

The failure of defense conversion in the 1990s led directly to the further militarization of police. Starting in 1994, “crime reduction” was awarded its own protected budgetary category. Three years later, Congress authorized the Defense Department under the 1033 program to transfer military equipment to law enforcement agencies. The outcome was most vividly apparent in the 2014 Ferguson protests when, as Missouri Representative Emanuel Cleaver said, violent police agencies laden with military gear made the Kansas City suburb look “like Fallujah.”

This history suggests that America has been preoccupied not by a “guns or butter” dilemma but with the notion of acquiring butter through the acquisition of guns: providing secure and well-compensated employment through state violence. The result is that, in both defense and policing, the sinews between state repression and economic prosperity are thick and plentiful. Police and correctional departments today account for between 25 and 40 percent of municipal spending; Cold War defense spending generally consumed between one-third and half of the federal budget until the mid-1970s. Like police budgets, defense spending provided hefty contributions to city and suburban tax bases and more broadly undergirded regional development, from suburban Boston to Seattle. Police work offers relatively high salaries, excellent benefits, and union protections; defense manufacturing workers similarly enjoyed some of the nation’s highest industrial wages and a degree of union density the envy of any organizer.

The correlations between policing and defense reveal how abolishing a political economy premised on violence must follow a broader agenda for economic and racial justice. The demand to divert funds from police departments to schools and hospitals must align with the broad measures necessary to secure a radically different set of public services: These include equitable health care for all, schools that are equitable (and not just well-funded), and the right to housing in communities that are safe from police violence. A reinvigorated program for defense conversion can also be incorporated into this project—and provide the basis for an expansive bloc that can mobilize against racial and economic inequality, both at home and abroad.

This strategy offers not only a means of dismantling police departments but an affirmative vision for the future that can peel away those dependent on the police state for income, family support, or their own perceived sense of security. It probably will not attract many law enforcement officers—but as with the California AFL-CIO’s plan for demilitarizing its membership, when faced with the extinction of a trade, unions can jump on board, if only to survive in a new municipal political economy. That’s why ending police unions as they currently operate—myopically focusing on protecting officers over any consideration of the harm they may pose to society—would force members to align more closely with the labor demands of hospitals, schools and other sectors that make up the social fabric, once defunding the police becomes a legislative reality in more areas.

Moreover, as the campaign to defund the police builds momentum, there is a persistent danger that its outcome will be determined in committees, subcommittees, and mayoral offices, where vested interests like police unions and prominent local businessmen have privileged access. All too often, this is how earlier defense conversion debates played out. While many cities and counties have more democratic representative bodies than the federal government, access remains limited to entrenched constituencies. Once wrung through these institutions and separated from mass politics, the defund movement can become diluted to be salutary to police and palatable to centrists and conservatives. This will not solve the problem of racist policing.

We can only get beyond such moderate “reforms” with a sustained democratic effort that relies upon mass political participation of Americans—and incorporates the democratic institutions with access to the levers of power, especially municipal unions. But activists have vowed to continue the protests until police brutality ends. This is good, and necessary. It accentuates the naked contrast between well-equipped police and ill-equipped health care workers. Most importantly, it makes more Americans across the nation increasingly aware of the connection between struggling communities and their well-funded police departments. The current defund the police movement has succeeded so far by replicating the successes of previous mass action against defense spending. To achieve a better world, it will need to learn from those movements’ failures, as well.