How many wars can the United States handle at any one time? The question became pertinent last week as the Trump administration, along with the president’s most militant supporters in Congress, rushed to define the civil unrest triggered by the police killing of George Floyd as a military problem requiring a military solution. President Trump put Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman General Mark Milley—in Trump’s words “a fighter, a warrior, and a lot of victories and no losses”—“in charge” of administration efforts to restore order in American cities. As is so often the case with Trump, no one quite knew what “in charge” signified, if anything.

Senator Tom Cotton, Republican of Arkansas and Trump loyalist, stood ready to translate presidential bluster into concrete action. Cotton is on the record calling for the deployment of up to five regular U.S. Army divisions—there are only six stationed in the continental U.S.—to do “whatever it takes to restore order. No quarter for insurrectionists, anarchists, rioters, and looters.”

In a military context, “no quarter” is a phrase redolent with meaning. It implies using maximum force and taking no prisoners. It suggests that the laws of war do not apply. It comes precariously close to calling for extermination—all pretty extreme stuff. Yet Cotton was by no means alone in his eagerness to use war as an instrument to dispose of any and all problems, large or small, in the nation’s path.

Indeed, members of the American political class to which Senator Cotton belongs (and to which Trump remains an outsider) have long been enamored with war, both real and metaphorical. Over the past half-century or so, U.S. forces have fought major wars in Vietnam, Iraq (twice), and Afghanistan. Interspersed among these large conflicts have been a dozen or so lesser skirmishes, typically classified under the anodyne heading of “armed interventions.” Over roughly that same period, U.S. presidents have initiated policies styled as wars that targeted poverty, cancer, drugs, crime, and terrorism. Throughout this long stretch of official belligerence, waxing and waning, but never disappearing altogether, has been the culture war, taking in conflicts over the agendas allegedly lurking behind major institutions like the courts, the universities, the media, and the centers of power in Washington, D.C. And now, of course, we are said to be engaged in a war against Covid-19. To listen to hawkish politicians and pundits, the U.S. is always “at war” against something somewhere.

No other nation on the planet can match America’s propensity for waging war against various enemies and pursuant to a myriad of purposes.

What explains this affinity for war and the easy lurch into the rhetoric of war in our domestic politics? Deeply imbedded in the American collective psyche is the conviction that war offers the most expedient way of achieving large purposes. After all, wars clarify priorities. They mobilize, empowering the state and justifying the expenditure of resources on a vast scale. They allow leaders to recast themselves as statesmen, motivated by a higher calling and immune to petty partisanship. With the onset of war, the meanness of everyday life gives way to heroism, sacrifice, fortitude, and moral purpose. War brings out the best in us—so, at least, more than a few politicians and many ordinary citizens profess to believe.

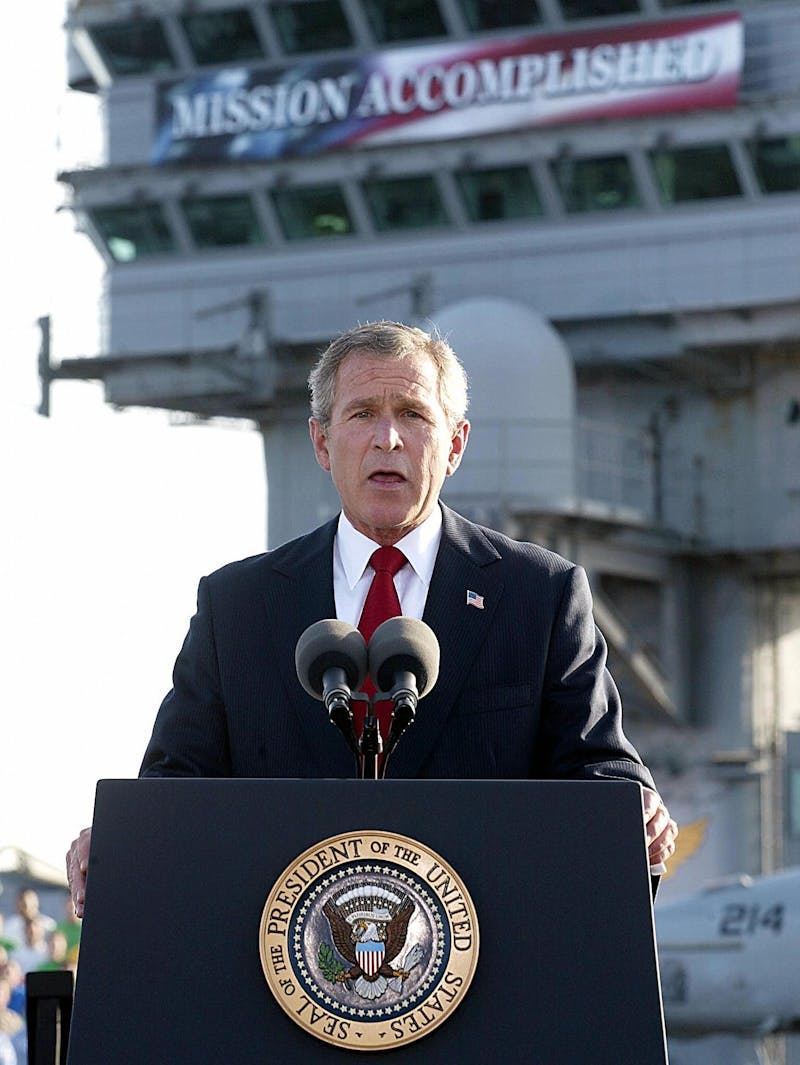

Speaking to the Congress just months after 9/11, President George W. Bush was certain that his just-announced “global war on terrorism” was going to make America a better place and Americans better people. When terrorists attacked New York and Washington, he said, “it was as if our entire country looked into a mirror and saw our better selves.”

We were reminded that we are citizens with obligations to each other, to our country, and to history. We began to think less of the goods we can accumulate, and more about the good we can do. For too long our culture has said, “If it feels good, do it.” Now America is embracing a new ethic and a new creed: “Let’s roll.” In the sacrifice of soldiers, the fierce brotherhood of firefighters, and the bravery and generosity of ordinary citizens, we have glimpsed what a new culture of responsibility could look like.

During the ensuing years, Bush’s expectations of war fostering a new culture of responsibility remained unfulfilled. Indeed, the nation’s recent wars have rarely made good on the expectations that inspired them.

None have yielded decisive victory. The Vietnam War resulted in a humiliating defeat. The global war on terrorism meanders along, now nameless and aimless. The invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan launched under the auspices of the “GWOT” did not achieve anything like the results promised. Much the same can be said for the various lesser conflicts that U.S. forces have entered into at the behest of modern presidents. Some, like Beirut and Mogadishu, culminated in disaster. Others, like the incursions into Grenada and Panama, produced nominal successes that the passage of time has reduced to insignificance. Meanwhile, poverty, cancer, drugs, crime, and terrorism all persist within our borders and show little evidence of disappearing.

As for the culture war, it certainly rages as fiercely today as it did back in 1991, when James Davison Hunter, a sociologist at the University of Virginia and author of the book Culture Wars, introduced the term into everyday American discourse. For proof, we need look no further than the confirmation hearings related to Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to a seat on the Supreme Court or the confusion and consternation stemming from charges that nearly 30 years ago Joe Biden, all but certain to become the Democratic Party’s presidential nominee, sexually assaulted a Senate staffer—an accusation that Biden adamantly rejects. Don’t expect the culture war to result in victory for either side of the battle—let alone to engender some heightened and hard-won state of cultural harmony—any time soon.

What is it with Americans and war? The coronavirus pandemic offers an opportune moment to engage this question in depth. Covid-19 puts into play a vast array of matters that Americans are accustomed to take for granted, among them assumptions about prosperity as an American birthright, the basic competence of democratically elected officials, rights of assembly and collective worship, and even the availability of food on grocery shelves.

Whatever eventually emerges as the nation’s “new normal,” it will almost certainly differ substantially from the conditions that prevailed before the pandemic. Covid-19 could even prompt Americans to reconsider their collective attitude toward war. Doing so just might increase the likelihood of that new normal aligning with the common good.

In his January 2002 State of the Union address, President Bush did get one thing at least partly right: When wishing to see their better selves, Americans do indeed look into a mirror. But what they see is not a true reflection: It is, rather, the nation as they choose to remember it at the outset of our half-century of misbegotten war, back when the American Century was kicking into high gear. More precisely, what they see is an image of themselves with soft backlighting framed by a carefully curated account of World War II.

At least until the twin bombshells of the present moment—the presidential election of 2016 and the coronavirus pandemic, compounded by the federal government’s bumbling response—the “good war” fought by the “greatest generation” had underwritten some semblance of a national consensus. U.S. participation in World War II put Americans back to work and thereby ended the Great Depression. But the war itself did much more: It restored the legitimacy of the American system, which the economic crisis of the 1930s had called into question.

After 1945, most Americans (though certainly not all) took it as a given that their way of life was vastly superior to any alternative. They also believed it to be durable, resilient—and, where deficient, correctable. The American way of life was the world’s gold standard back when the world was on a gold standard. It made good on promises.

Always, of course, there was dissent. Always there was a radical fringe. But even during dark times marred by assassination, riots, and mass protest, the postwar consensus held. Even in 1968, marked by the Tet Offensive, the murder of Martin Luther King and a second Kennedy brother, cities in flames, and the tumult of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, the forces upholding the postwar status quo were never seriously threatened. The election of Richard Nixon as president in November of that year affirmed as much.

Of course, this postwar consensus was itself famously the product of war—the global conflict that definitively placed the U.S. in the role of the protector of the democratic, capitalist West (and all too often, as the self-appointed policeman of the world at large). The new postwar consensus worked within the U.S. to affirm the basic social order—and by extension, a political economy centered on corporate capitalism. More important still, it removed most remaining global restraints on mustering American power to police the international order. World War II empowered the U.S. to lead. And leadership almost immediately took on military connotations. Name your issue: developing and deploying thermonuclear weapons; committing to the defense of Western Europe; sending U.S. combat troops into Korea; replacing the French in Indochina; conspiring to overthrow regimes not to Washington’s liking in Tehran, Havana, and elsewhere; converting the Persian Gulf into a theater of permanent armed conflict. In each and every case, proponents of action or instant readiness to act enjoyed the benefit of the doubt—and usually the upper hand when it came to charting policy.

The new consensus was also military-minded in another respect: It was relentlessly triumphalist, to the point of making any dissent seem retrograde to reactionary. To argue the contrary position was to be derided as an isolationist, an appeaser, or a pacifist—and to be rendered ineligible for election to high office. Given the obvious benefits that drawing on collective memories of World War II created for interventionists in foreign policy debates, it was probably inevitable for the same dynamic to take hold in the domestic sphere, as well. Hence, the war metaphor came into its own in the 1950s as a mainstay of American political discourse, complementing the rhetoric employed to justify actual wars. Always the ostensible lessons of World War II hovered in the background. Always, too, the record of America’s industrial and military achievements during that conflict sustained the conviction that ours is a nation capable of doing anything that we set our minds to.

The end result was a seamless garment woven of convenient memories. As the war itself slipped into the past, it served as a sort of drop cloth concealing from Americans what the nation was actually becoming. What counted was who we had been and what we had done from 1941 to 1945. Always and forever, we remained the people who—at least in our own minds—had defeated the Nazis. This baseline conviction conferred upon us a new world-historic array of privileges, obligations—and above all moral authority.

On May 10, Tom Brokaw, veteran network anchor and the renowned 1990’s chronicler of the greatest generation, appeared on the NBC Nightly News to reflect on the meaning of Victory in Europe Day, which 75 years before had ended the war in Europe. His commentary was drenched in sentimentality. But above all, Brokaw insisted, the anniversary of VE Day provided an occasion to “celebrate and remember all the victories we have had together.”

In the midst of an ongoing pandemic that has killed more than 100,000 Americans, Brokaw’s allusion to all the victories “we” have enjoyed together might strike some as odd, if not downright inappropriate. Yet Brokaw was performing a duty of sorts. A member in good standing of the mostly male, mostly white American elite, he figures prominently among those who take it upon themselves to put events into perspective for ordinary citizens, in effect explaining the meaning of history.

This was indeed the impossible-to-miss subtext of his brief televised commentary: to situate Covid-19 in relation to “all the victories” that had their point of origin in the 1945 defeat of Nazi Germany. Brokaw was exercising the prerogative of remembering what he believed all Americans ought to remember—while also discarding or consigning to the margins memories that might introduce unwanted complications.

Brokaw’s testimonial serves as a reminder of the role that sanctifying World War II has played in dodging complications. The “Disneyfication” of the war, to use the term coined by the late scholar Paul Fussell, makes it possible to skirt around a multitude of uncomfortable truths. And while a few curmudgeonly Fussells are always out there, it’s the uplifting message of the Brokaws that commands a larger market share.

Yet it may well be that today we should be listening to the curmudgeons and contrarians. In this context, consider Dwight Macdonald’s famous essay “The Responsibility of Peoples,” published in his magazine Politics, just as the fighting in Europe was beginning to wind down in early 1945. As a journalist, Macdonald was something close to an anti–Tom Brokaw. His purposes were anything but celebratory. His aim was to discomfit.

“In the present war,” he charged, “we have carried the saturation bombing of German cities to a point where ‘military objectives’ are secondary to the incineration or suffocation of great numbers of civilians.” By deferring to our Soviet allies, “we have betrayed the Polish underground fighters in Warsaw into the hands of the Nazis, have deported hundreds of thousands of Poles to slow death camps in Siberia, and have taken by force a third of Poland’s territory.” More directly, “we have followed Nazi racist theories in segregating Negro soldiers in our military forces and in deporting from their homes on the West Coast to concentration camps in the interior tens of thousands of citizens who happened to be of Japanese ancestry.” And Americans had made themselves complicit in the greatest of all Nazi crimes “by refusing to permit more than a tiny trickle of the Jews of Europe to take refuge inside our borders.”

Of course, Brokaw’s seventy-fifth-anniversary remembrance allows no room for any such objections. Yet each one of Macdonald’s charges was then and remains today undeniably accurate. And his accusatory use of the first-person plural in leveling them was hardly accidental. In a democracy, he was insisting, citizens cannot escape responsibility for crimes committed in their name. Military necessity cannot justify evil. Brokaw’s “we” gave Americans a pat on the back; Macdonald’s gave them a poke between the eyes.

Here we come to the crux of the issue. U.S. participation in World War II was necessary and may have been unavoidable. Even so, American conduct during the war was anything but “good.” Likewise, the generation called to serve in the war did indeed make heroic sacrifices and helped defeat—more provisionally than anyone might have guessed—the fascist menace, but by no reasonable moral reckoning could they be designated “greatest.” (Just ask any returning black veteran, who found the postwar home front riddled with the same bitter forces of racism, both north and south, that distorted his life chances in the prewar American consensus.)

What’s more, the war’s broader geopolitical outcome produced results that were mixed at best: more than satisfactory for my parents, who came home, left the service, got married, started a family, and enjoyed a middle-class life; far less satisfactory for my various distant relatives back in Lithuania who, lacking my grandfather’s foresight in making a timely departure for America, ended up living in a police state.

Macdonald may well have been the first writer to take issue with the conventional narrative of the war, even as it was still forming. In the decades since, others, like Fussell, have expanded on his argument. Yet as Brokaw’s comforting tribute to VE Day reminds us, efforts to dislodge the “good war” narrative have been to no avail. To this day, Americans vastly prefer Brokaw’s interpretation of the war to Macdonald’s.

As a result, the consequences of America’s subsequent affinity for war, whether real or ersatz, take a backseat to gearing up for the next go-round. Having only recently survived a war scare with Iran, official Washington is today much taken with the possibility of a military showdown with China. Writing in the New Yorker, Evan Osnos sounds the alarm: “China is preparing to shape the twenty-first century, much as the U.S. shaped the twentieth.” Washington Post columnist David Ignatius assesses growing Chinese military capabilities and wrings his hands about “America’s vulnerability.” Ignatius’s argument reduces to this: China is now strong enough to defend itself against a U.S. attack. At any rate, the bugles are sounding: It’s time to saddle up.

Hence, too, the belief that treating the response to Covid-19 as a military enterprise offers the most expedient way to restore American society to health. Rosie the Riveter is back, this time wearing a red, white, and blue face mask, but still proclaiming “We can do it!” Meanwhile, the Air Force Thunderbirds and the Navy’s Blue Angels perform flyovers of major American cities to honor the “warriors,” i.e., doctors, nurses, and EMTs, who are serving on the “front lines,” i.e., in hospitals. “This is war,” writes former Obama national security adviser Susan Rice in The New York Times, “the most consequential since World War II,” while taking aim at President Trump for failing to “display the leadership we need from a wartime commander in chief.” And in his first “shadow briefing” on the coronavirus, presumptive Democratic nominee Joe Biden likewise castigated Trump for failing to live up to his own characterization of himself as a “wartime president” over the course of the pandemic. “To paraphrase a frustrated President Lincoln writing to an inactive General McClellan during the Civil War,” Biden announced, “‘if you don’t want to use the army, may I borrow it?’”

In reality, the last thing Americans need today is more war, whether actual or imagined—or a president who fancies himself a field marshal. Indeed, restoring the nation to health should begin with the recognition that a misguided tendency to see war as a solution, whether to a deadly virus or a wave of civil protests, or as a response to a rising China, may well be the ultimate expression of the illness afflicting our nation.

What precisely is the nature of that illness? Our understandably intense preoccupation with Covid-19 and equally understandable distress at the Trump administration’s mishandling of the pandemic have diverted attention from this larger question, which ought to be central to the upcoming national election but is not. This omission alone all but guarantees that whoever wins in November—whether the draft-dodging president who promised to end our “endless wars” but has not done so or the challenger who likewise avoided military service and, as a U.S. senator, voted in favor of the Iraq War—will accomplish little apart from kicking the can down the road.

Our real problem is this: The postwar consensus has collapsed and is gone for good. In its heyday, it offered economic arrangements that provided steady employment while reducing inequality. For a time, it offered a modest but workable conception of collective purpose, centered on FDR’s “Four Freedoms.” At least briefly, it offered an imperfect but useful definition of America’s role in the world, centered on opposing communism.

With the passage of time, none of these still pertains. Worse, as the postwar consensus decayed, it gave rise to a poisonous legacy: gaping inequality, tied to the persistence of deep-seated racism; bitter disagreement regarding the operative definition of freedom, pitting secularists against moral traditionalists; and an entrenched, shamelessly dishonest national security establishment that constantly invents new threats while diverting attention from its own myriad failures. As a means to address these concerns, war is at best a distraction and at worst a menace.

Dwight Macdonald concluded “The Responsibility of Peoples” with a quote from the mystic Simone Weil. “Modern war,” Weil wrote, “appears as a struggle led by all the State apparatuses and their general staffs against all men old enough to bear arms.” Yet, “the great error of nearly all studies of war,” she continued, “has been to consider war as an episode in foreign politics, when it is especially an act of interior politics.”

True enough in her own day, Weil’s judgment requires amendment in our own. In the U.S. today, war functions as a conspiracy, employed by the state and other militarized institutions to keep the people in their place. The great error in our present-day understanding of war stems from our inability or unwillingness to confront the ruinous role that war has played in corrupting and trivializing our politics. The responsibility of the American people today is to say no to further war and thereby begin the process of saving their country.

As for Tom Cotton, mark him down as an enemy of the people.