During Ornette Coleman’s legendary 1959 run of shows at the Five Spot club in New York, there was a joke going around: “A waiter drops a trayload of drinks and a man says to his lady-friend, ‘Listen honey, Ornette’s playing our song.’” The punch line is a doozy, capturing the nightclub’s dankness (capacity: 75; ambience: urine), the hype around Coleman’s radical new sound, and the confrontational difficulty of his music.

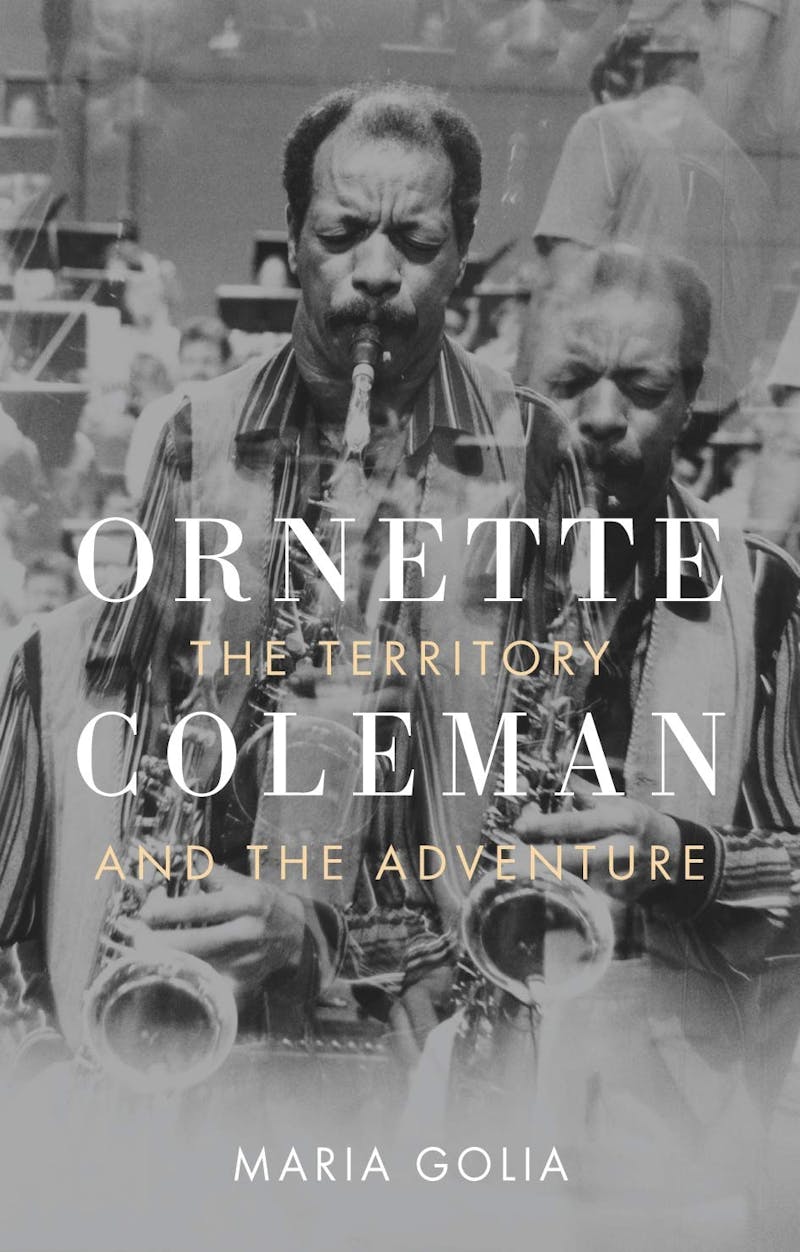

The first night of that run, November 17, represented a turning point in American jazz. There were other bebop musicians playing with experimental forms in the 1950s, like John Coltrane and Miles Davis, but Coleman brought something wholly unexpected to his signature white plastic saxophone. His sound’s arrival in New York made Coleman “an overnight underground sensation,” Maria Golia writes in her new book, Ornette Coleman: The Territory and the Adventure.

He was the shock of the new. Before Coleman, “free jazz” was an eggheads’ pursuit, so obscure that he and his band once had to bail out of a gig that was advertised as a “Free Jazz Concert,” which a crowd had assumed meant no entrance fee.

Golia writes scenically about Coleman’s birthplace, Fort Worth, Texas, where Jim Crow and music were everywhere. Against the background of the “red meat and crude oil” industries, Coleman grew up down by the railroad tracks. Trains rattled constantly, and bells rang all the time, inspiring 1920s “hobo” singers like Henry “Ragtime Texas” Thomas. The author Albert Murray calls this musical logic “railroad onomatopoeia.”

With a pointillist’s talent for detail, Golia shows how Coleman’s origins in Texas blues gave way to abstraction on landmark records like The Shape of Jazz to Come (1959) and At the Golden Circle (1966), ultimately leading him to create the musical paradigm he called “harmolodics.” Conventional jazz harmony is religiously chord-based, with soloists improvising within each key like balls pinging through a pinball machine. Coleman, in contrast, imagined harmony, melody, and rhythm as equal constituents. He sometimes said that he played around a melody, in such a way that he could hear it was there, but some listeners could not.

Coleman was profoundly skilled and played with all kinds of bands as a traveling musician in his twenties (after he was fired from a local band for improvising during the national anthem, or so the story goes). But peers like Miles Davis and Charles Mingus felt that he was dispensing with the necessary disciplines in favor of something easier. As Jackie McLean put it, “You spend your whole life making a three-piece suit that’s incredible, and this guy comes along with a jumpsuit, and people find that it’s easier to step into a jumpsuit than to put on three pieces.”

It’s the old cliché you’ll overhear in a museum show of abstract art: “My three-year-old could do that.” Just like Jackson Pollock, however, Coleman was innovating deliberately and with control, according to the principle of free inquiry Allen Ginsberg named as key to his generation’s creativity: “The whole point of modern poetry, dance … performance, prose, was the element of improvisation and spontaneity … and jazz was a model for almost everybody.”

Golia clarifies that Coleman’s atonality never diminished his jazz’s “requisite virtuosity,” although it could certainly sound bewildering. Instead, it “proposed an alternative means for its expression.” Collaboration and close listening among a practiced ensemble of musicians were essential to accomplishing a state of intimacy Coleman called “unison.”

Describing the way Ornette Coleman’s music sounds is a challenge, and Golia rounds up some delightful attempts by music critics past. “Eldritch wrongness” is a phrase from Brian Morton’s obituary of Coleman for The Wire, describing the sinister sounds Morton thought were the result of Coleman’s misapprehensions about musical theory as a child. Francis Davis wrote in The Atlantic Monthly in 1972 that, “Perhaps the trick of listening to his performances lies in an ability to hear rhythm as melody, the way he seems to do, and the way early jazz musicians did,” which is genuinely helpful advice. In notes hastily jotted while “under the spell of a first discovery” of The Shape of Jazz to Come, Martin Williams wrote that “if you put a conventional chord under my note, you limit the number of choices I have for my next note; if you do not, my melody may move freely in a far greater choice of directions.” For Williams, this innovation was an escape hatch for a musical form in stasis: “Someone had to break through the walls that those harmonies have built and restore melody.”

Critics were as much in search of a language for the avant-garde as for a summary of a record. Coleman resisted critical language, Golia notes, quoting his disdain for people who “don’t trust their reactions to art or music unless there is a verbal explanation for it.” Coleman had a gnomic way with words himself, however. “How do you turn emotion into knowledge? That’s what I try to do with my horn,” he once wrote. In the liner notes to Change of the Century (1960), he reminds us that “the only thing that matters is whether you feel it or not. You can’t intellectualize music; to reduce it analytically is often to reduce it to nothing very important.”

A long section of The Territory and the Adventure is about an arts venue in Fort Worth called Caravan of Dreams, complete with utopian geodesic domes and a millionaire funder. Coleman played there many times in his later life, when Fort Worth belatedly recognized him as a hometown hero. Golia, it turns out, was often the person at the door taking tickets: She worked there from 1985 to 1992.

So we finish where we started, at a jazz club. It’s sad to think of long-lost venues like the Five Spot, where all sorts of different people jumbled together. The critic Whitney Balliett remembers it as “intricately awash with music and reaction, reaction and music.” Even the Caravan of Dreams is a conference center, now. It is also sad to contemplate how little remains of that old avant-garde New York music scene, which blossomed under the direction of black adventurers like Coleman.

Then again, not everything has changed. In the very same year as Coleman’s Five Spot debut in 1959, Miles Davis had his head cracked open by a cop who tried to get him to “move on’’ during a smoke break between rehearsals. The “free” in “free jazz” is an ambivalent word. It doesn’t refer to the absence of oppression or musical rules, but instead the struggle to imagine a place beyond them both. In that sense, Coleman’s definition of freedom was radically inclusive, both politically and musically. As he once remarked, “Nobody has to learn to spell to talk, right?”