On the night of May 30, 1964, the Alabama-born singer Odetta watched a thunderstorm explode over Brussels from her room at the Amigo hotel. She was on her first European tour, promoting her twelfth studio album. From the distance of half a century, her tour guitarist Peter Childs remembers how “radiant” Odetta looked as the lightning illuminated her face, rain pummeling the cobblestones below.

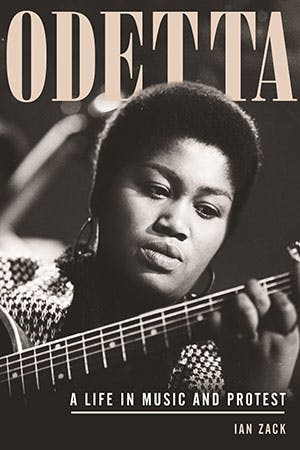

Childs remembers the moment well because his boss was not always so happy. Odetta was one of the most famous singers in America in the late 1950s and early ’60s. Her career was bookended by a hardscrabble childhood and equally tough middle age, although she sang to enraptured audiences into her twilight years. Now largely forgotten by younger generations, Odetta has never since received the recognition her art is due. Ian Zack’s new biography, Odetta: A Life in Music and Protest, is here to repair that gap in the record.

Sara Marcus wrote in a 2015 TNR piece “Against Musicians’ Biographies” that traditional songs (she uses the example of “Water Boy,” an Odetta standard) are more important than the people who sing them, because they gain their value by being handed down over generations. Zack’s book begs to differ on simple musical grounds: Odetta was such a transformatively magnetic performer that she continues to influence the meaning of her repertoire.

Born Odetta Holmes on the last day of 1930, she took her stepfather’s last name, Felious, but dropped it in favor of a mononym as soon as she began performing. She was ridiculed as a child for being big and tall, and internalized that teasing. She was trained in opera but hit the big time after falling in with the folk crowd in the early 1950s, singing spirituals and old traditional tunes like “John Henry.” In Zack’s biography, Pete Seeger recalls coaxing Odetta to join a hootenanny singalong sometime in the ’50s. She was shy at first, but “when she was persuaded to sing, power, power, intensity, and power!” Odetta’s voice was a force to make you tremble.

National fame came in 1957 with her album of spirituals and traditional ballads, Odetta Sings Ballads and Blues. When Odetta appeared on TV, singing songs from the canon of black grief, the intensity of her spirituals hypnotized the (mostly white) audience. She sang classic work songs like “Take This Hammer” with as much solemnity as Paul Robeson, but lit up by the gusto and passion of something rawer, less formal.

Black women were scandalized, inspired, or both by her short, natural Afro, one of the first of its kind to appear on screen (Angela Davis copied her). The civil rights movement in general, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in particular, also found a troubadour in Odetta, who grew up under Jim Crow in Birmingham and bore the psychological scars to match. She became close with Martin Luther King Jr., and her songs became the soundtrack to his mission. Odetta will always be remembered for singing “Oh Freedom” at the March on Washington in 1963.

Her celebrity always had one foot in civil rights and the other in the American folk-revival scene, which, in the late 1950s, was recovering from Joseph McCarthy’s persecution and in need of young, charismatic talents. Those two worlds were interconnected, of course, but Odetta’s influence among white musicians is difficult to overstate. Bob Dylan, whose career would eclipse hers in only a few years, decided to sing behind an acoustic guitar after hearing an Odetta L.P. play in a record shop in 1950s New York. Carly Simon fainted when she first met her.

Odetta’s big problem in the 1960s was musical. The splendid dignity and gravitas of her classically influenced style, so meaningful to the folkies, just didn’t swing the way that rock and roll did. She struggled to find a new sound once folk dropped out of fashion. She didn’t have the gravel or rhythmic flair of Aretha Franklin, who by 1970 had displaced Odetta as the preeminent African American female singer in the public imagination, which didn’t have space for two.

Odetta enjoyed an enthusiastic following across the world for the rest of her life, as countries like Japan, the Soviet Union, and Germany caught up to the folk movement. Back in America, she spent the 1970s and ’80s in Manhattan, taking any gig she could get but struggling to get by. In the 1990s, she enjoyed a surprise burst of musical growth when MC records signed her to make a blues album. Odetta’s 1999 record, Blues Everywhere I Go, was a genre hit, and she was delighted to earn a Grammy nomination.

She never had a good manager, and the husband who gave her the last name Gordon seems to have spent plenty of her money on himself. Those factors made Odetta’s creative struggles harder. Zack records her laments of racism in the industry, and it is little wonder she became embittered in later years. At sound checks, the older Odetta put technicians and other assistants in their place with sharp, regal rebukes.

Her audience, for at least the first decade of her career, was predominantly white, for the simple reason that the record companies and managers packaged and marketed her to them. As Zack notes, sometimes the reviews in the white press of her early shows were almost bizarrely superlative, while insulting at the same time. “Odetta is a Negress who seems six-foot tall and has a baritone voice,” said the New York Herald Tribune, just before praising her to the skies and observing that her “bearing is that of a princess.” White critics sometimes fetishized Odetta’s “old Negro spirituals,” as they called her songs, as if she were more an embodiment of black historical pain than a real person.

Real she was, and Odetta’s life story takes on huge significance and scale in Zack’s book, as he explains how her talent was buffeted by the winds of American history like a tree flexing in a gale. Biographies can help us to conceptualize the slippery phenomenon we call being alive, especially as it relates to the passing of time. Is life made out of instants, like lightning flashing on a face in a storm, or is it some mystical force that flows across time, bigger than any one person? Odetta brims with the life of its forgotten subject, showing us that we have a lot of cultural history to relearn and many losses yet to mourn.