“In times such as these, you always have experts who believe that they know best for everybody. You have some folks who think that government ought to take over everything in times of crisis—that they, as government officials, know better than individual citizens.”

These were the sentiments of Republican Mississippi Governor Tate Reeves when a reporter asked him to explain his minimal approach to contain the rapid spread of the coronavirus in his state. Alabama’s GOP Governor Kay Ivey also initially rejected any serious statewide action to protect her citizens from Covid-19. “Y’all, we’re not California. We’re not New York. We’re not even Louisiana,” she declared. California was the first state in the nation to institute a mandatory stay-at-home order, while New York’s actions were lethargic and confused; as a result, as of April 28, there had been 1,786 deaths from Covid-19 in California versus 22,623 in New York state. Louisiana, which failed to suspend the annual Mardi Gras festival this year, is one of the foremost hot spots for the coronavirus on the planet. An April Forbes article, meanwhile, bears the astonishing title “In Idaho, Lawmakers Flout Stay-At-Home Requirements—And Encourage Others To Follow Suit.”

Are these behaviors, even if misguided, ramifications of the vaunted liberal tradition in America? John Stuart Mill, who codified the postulates of classical liberalism, held that individual autonomy allowed people to pursue any course of action they wanted, even if it was destructive to themselves, as long as it wasn’t injurious to others. The irresponsible attitudes limned above—fully shared by the president of the United States—represent a mutant variant of liberalism that, in addition to being self-endangering, is a threat to the entire surrounding community.

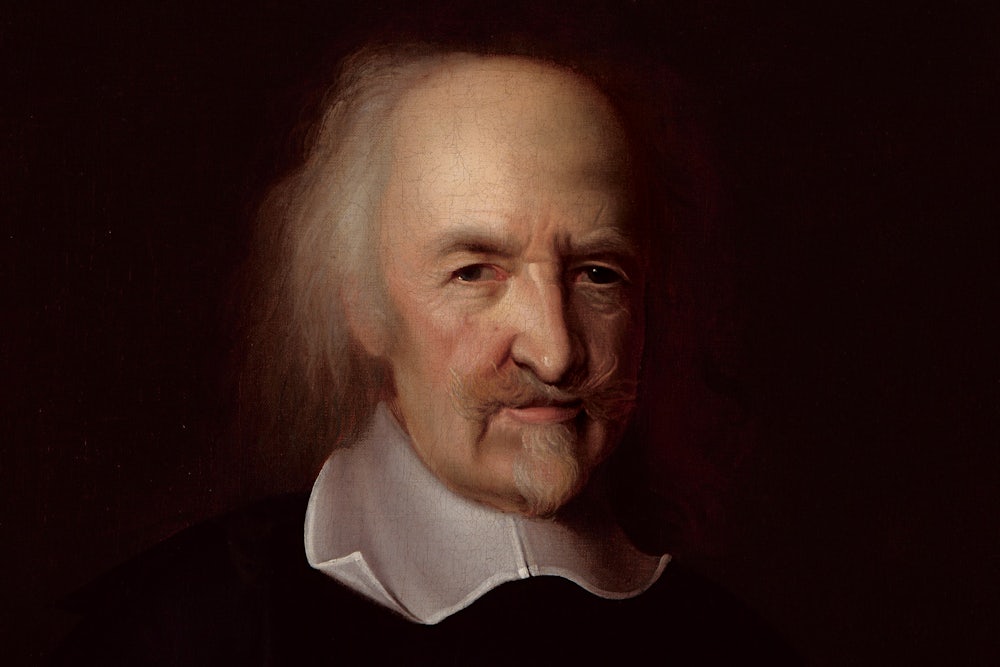

There is a chain of ironies that begins with former U.S. National Security Adviser Susan Rice’s New York Times op-ed of April 7 accusing President Donald Trump of creating a “Hobbesian jungle where it’s every man for himself.” She refers not only to individuals and institutions engaged in battling the virus head-on, but also to the 50 states that constitute the federal system; early in his botched handling of the crisis, Trump declared that the national government was to serve only as a distant “backup” to the states in this war, not the lead combatant on the front lines. The chief irony here is that Thomas Hobbes himself had forcefully argued that human nature required the strong hand of an authoritarian government—his famous Leviathan—to guarantee public order and safety. This was indeed a government’s foremost duty; only by fulfilling it, Hobbes maintained, could political authority create a modest space of individual freedom for its subjects. This last proviso is what gives Hobbes pride of place, in front of the more libertarian John Locke, as the first theorist of liberalism.

Another more recent historical irony is that Herbert Hoover, as secretary of Commerce for conservative President Calvin Coolidge, oversaw the first massive federal involvement in local disaster relief, following the devastating Mississippi River flood of 1927. A further irony, ensuing from that one, inheres in Mississippi Governor Reeves denigrating those “who think that government ought to take over everything in times of crisis.”

Contemporary British political philosopher John Gray, in a recent discursive essay in the New Statesman, “Why this crisis is a turning point in history,” offers pithy thoughts on the theme of Hobbesian versus Lockean liberalism. Gray, during his tenure as a professor at Oxford, specialized in liberal political philosophy and was a reigning authority on Mill. Gray argues that the British state, “at its core,” has always been essentially Hobbesian. The British system has always relied on a strong central government to provide domestic tranquility and protection from the public enemy, though it’s customarily done so with “the consent of the governed” (a Lockean concept, for balance). “Being shielded from danger has always trumped freedom from interference from government” in Britain, Gray writes, evoking a tradition considerably at odds with today’s fiercely anti-state conservative consensus in America. Now, in a situation of extraordinary danger, the once-towering British state, weakened by years of “imbecilic” Conservative Party austerity, is, he submits, being reconstituted and expanded on an unprecedented scale. Gray argues that, thanks to its new crisis footing, the British political system will emerge from its coronavirus ordeal intact. “Not many,” he boasts, “will be so fortunate.”

Gray notes that the greatest successes in dealing with Covid-19 have been in Asia, most notably in South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore. He suggests that their outstanding record is the product of cultural mores prioritizing collective well-being over personal liberty. By contrast, the uneven liberalism of the United States has produced such large populations of vulnerable people—the medically uninsured, the incarcerated, the homeless, the drug-addicted—that the nation might well have to choose between a protracted and ruinous economic shutdown and an uncontrollable spread of a lethal virus throughout the land.

Gray shows little inclination, however, to abandon the liberal tradition wholesale; he seeks, as do I, a balance between individual liberty and—to once again invoke a prized concept of Benjamin Barber—communal liberty. “It is only by recognizing the frailties of liberal societies that their most essential values can be preserved,” he writes. “Along with fairness, they include individual liberty, which as well as being worthwhile in itself is a necessary check on government. But those who believe personal autonomy is the innermost human need betray an ignorance of psychology, not least their own. For practically everyone, security and belonging are equally important, often more so. Liberalism was, in effect, a systematic denial of this fact.” Thomas Hobbes would no doubt agree.