The search for a vice president follows a series of rituals as stylized as those of the Japanese tea ceremony.

There are leaks, carefully orchestrated by the campaign to appease various constituencies, expressions of humility by potential veeps, and pious promises from the candidate that political considerations would never enter into a decision this momentous. Meanwhile, campaign reporters, desperate for storylines now that the primaries have ended, pursue every thinly sourced rumor as if it came with a Pulitzer Prize attached.

Following that familiar script, Joe Biden is slated to launch by the end of this week teams to do the background research on possible vice presidents, with the goal of narrowing the list of contenders by July. Ever since he flatly stated in his final debate with Bernie Sanders that his running mate would be a woman, the press and the pundits have been circling around the five seemingly most obvious choices: his former presidential campaign rivals, Senators Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris, and Amy Klobuchar, along with Governor Gretchen Whitmer (denounced by Donald Trump as “that woman in Michigan”) and 2018 Georgia gubernatorial candidate, Stacey Abrams, who has become a TV regular as she stumps for the job. Other candidates, particularly a handful of strong Latina contenders, will undoubtedly get their moment in the limelight. But barring a surprising turnabout, attention will keep returning to the frontline five.

The endless spins of the wheel as the media play Veepstakes Roulette obscure certain lasting truths surrounding the search for a second banana. As Richard Nixon shrewdly observed in 1968, “The vice president can’t help you. He can only hurt you.” A half-century later, with partisan sentiments hardening on both sides, this dictum is even more on target than it was in the days when Nixon tapped Spiro Agnew.

There is no single running mate who can

emerge, like Wonder Woman, with the preternatural power to enhance black

and Latino turnout, reach out to hard-core Sanders supporters, and appeal to

wavering Republican voters in the Midwest. This election is already shaping up to be a

referendum on the dangerous, dilatory, and desperate presidency of Donald Trump.

As such, it is unlikely to pivot on how the Democratic VP measures up against

Mike Pence. In the end, Biden’s chemistry with his eventual running mate will almost certainly matter more than crass political calculations.

Biden will have to deal with a weird affliction that hits former vice presidents when they are nominated for the Oval Office job of their dreams. The track record of former VPs in picking their own number twos is impressively dismal. Agnew, of course, became the first vice president since John Calhoun in 1832 to resign the office to avoid being prosecuted for taking bribes. In 1988, George H.W. Bush tapped the hapless Dan Quayle, who in his autobiography admitted that he came across as “the guy on the game show who’d just won the Oldsmobile.” Al Gore’s 2000 selection of Joe Lieberman (a leading critic of Bill Clinton’s sexual conduct) made some political sense at the time. But by 2006, the hawkish Lieberman was forced to run for reelection as an independent after he lost the Democratic primary for his own Senate seat. Two years later, John McCain nearly put him on the Republican ticket.

But Biden has an advantage that these former vice presidents lacked: His closeness to Barack Obama seems genuine rather than a convenient media creation. In contrast, Dwight Eisenhower said he needed a week to recall a pivotal decision that Nixon made as vice president. Barbara Bush always resented that the Reagans never invited her or her husband to the family quarters in the White House during their eight years in office. And in 2000, Gore pointedly avoided asking Clinton to campaign for him even in a state like Arkansas.

That’s why Biden knows that the choice of a running mate, ultimately, is an intensely personal one. Unlike an errant Cabinet pick, a vice president can’t be discarded at will. Nor, these days, can a VP be forgotten (as Lyndon Johnson was during the Kennedy years) until the president needs him to attend a second-tier foreign funeral. A president and a vice president are as closely entangled as a family, sometimes dysfunctional and sometimes genuinely close.

Political reporters tend to overreact to what was said yesterday, as if immediacy were synonymous with truth. But the best clues about Biden’s thought processes on picking a VP are not his recent statements, which echo the boilerplate lines that all de facto nominees use to dampen speculation. In early April, for example, Biden blathered to a questioner at a virtual fund-raiser, “I’m looking for someone who will be a partner in the progress. Someone who is simpatico.”

More revealing was what Biden said about the VP search during the wilderness phase of his quest for the White House, when it required an almost religious leap of faith to believe that the former vice president would ever get to pick a running mate of his own. In late November, at a sparsely attended town meeting in Winterset, Iowa, Biden seemed genuine as he tried, rather awkwardly, to articulate the lessons he had learned during his eight years as Barack Obama’s sidekick.

Biden emphasized that a president needs “to have the confidence in the competence of a vice president so that you can delegate authority.” The other factor is compatibility and trust. “Whomever I would pick if I were the nominee would have to be someone I knew who is philosophically in tune,” Biden said. “That was prepared to support what I ran on … and not have any fundamental disagreement with me.”

Of course, back in November, Biden had not yet explicitly pledged to put a woman on the ticket. And all predictions about the veepstakes should be tentative since, in these tumultuous times, events could reshape Biden’s decision with the Democratic convention still nearly four months off. Yet his words in Winterset—the fruit of eight years of thinking about the vice presidency—provide a useful framework for handicapping the competition for the heartbeat-away job.

Biden’s VP criteria should quiet some of the fanfare surrounding Elizabeth Warren. Yes, in the flush of victory, Biden adopted many of Warren’s positions on bankruptcy law, an issue that bitterly divided them back in 2005. But it takes a gymnast’s stretch to describe Warren and Biden as “philosophically in tune.” And even if he did select Warren in an attempt to paper over some of the policy rifts in the Democratic Party, she likely wouldn’t satisfy the Bernie-or-bust purists. Her age also works against her. In the midst of a pandemic, it would be politically risky to pair Biden, who, at 77, will be the oldest presidential nominee in history, with Warren, who turns 71 in June. (Warren’s 86-year-old brother, Donald Herring, tragically died from Covid-19.)

After nearly a half-century in Washington,

Biden is probably also looking for a VP whose “competence” involves more than

just a mastery of the levers of state government. This is a major obstacle for

Stacey Abrams who, despite her obvious political talents, has only ever served

in the Georgia legislature. It may also be why Abrams allowed herself to express frustration

in a recent interview on

ABC’s The View, in which she implicitly pressured Biden to choose a woman of

color. In response to a question about the veepstakes, she said, “I would share

your concern about not picking a woman of color because women of color—particularly

black women—are the strongest part of the Democratic Party.”

When Biden made his mid-March debate pledge to put a woman on the ticket, he also went out of his way to reiterate his intention to nominate an African American woman to the Supreme Court. That promise didn’t make headlines at the time, but influential Democrats interpreted the juxtaposition of the two pledges as a way to dial down the pressure on Biden to pick Abrams or Kamala Harris as his running mate.

After three years in the Senate, and blessed with high name recognition from her own ill-fated presidential campaign, Harris makes sense on paper as a Biden running mate. But note those key words: on paper.

When he discussed his relationship with Obama in Winterset, Biden stressed, “We always completely trusted each other.” Harris was close to Biden’s late son, Beau. (She was California attorney general when he held the same job in tiny Delaware.) But she may have permanently forfeited those family bonds of trust when she launched a surprise attack on Biden’s record on busing in the 1970s during a July debate. It probably didn’t help that the cautious Harris put off endorsing Biden until after the March 3 primary in her home state of California, which Sanders won.

Covid-19 may complicate Biden’s decision in unexpected ways.

On one hand, it makes it harder for him to choose a lesser-known Latina contender like New Mexico Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham or Senator Catherine Cortez Masto of Nevada. Because of the nationwide lockdown, Biden can’t travel around the country testing out his campaign-trail chemistry with those politicians, and both would need a national tour with Biden to boost their name recognition. Under the current circumstances, it probably is not advisable to pick a VP who would send many voters rushing to Wikipedia.

Meanwhile, the pandemic has elevated

governors like Michigan’s Gretchen Whitmer. Of course, she, like Abrams, has spent

most of her public career in the state legislature, but, according to a recent Fox News poll, she now boasts an

approval rating of 63 percent in Michigan, a swing state Trump won by as few as 10,000 votes four years ago. The big question is whether Biden believes that the pandemic has given Whitmer the national experience he craves, especially since a Midwesterner like Klobuchar would probably appeal to a similar swath of voters.

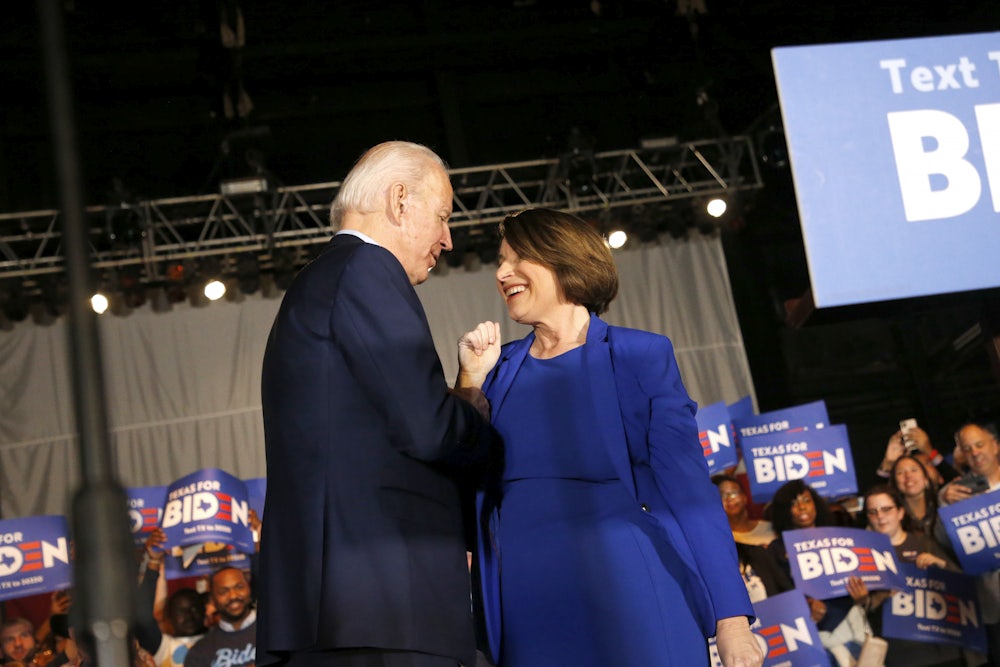

Klobuchar, in fact, comes closer to meeting Biden’s Winterset criteria than any other vice-presidential contender. Unlike Harris, the three-term Minnesota senator never attacked Biden personally, even though they were both competing for the same tranche of moderate voters. And Biden and Klobuchar also boast a similar theory of how to appeal to persuadable 2020 voters: They both frequently praise the late John McCain as a way to reach out to troubled-with-Trump Republicans.

Biden, an old-school politician, prizes loyalty, and he has gone out of

his way to praise the Minnesota senator, gushing at the end of a recent

joint podcast, “I

wouldn’t be the nominee if you hadn’t endorsed me. You won Minnesota for me.” (Her endorsement on the eve of the March 3 Super Tuesday primaries allowed Biden to carry Minnesota without ever campaigning in the state.)

For all the help that Klobuchar might offer in Wisconsin and Michigan (two states that Hillary Clinton lost in 2016 by a total of 35,000 votes), her selection would represent the political version of the ancient medical dictum, “First, do no harm.” Of course, like math students doggedly attempting to square the circle, armchair pundits (and probably some Biden advisers) will continue to cast around for a magical running mate who could arouse unstoppable enthusiasm among all parts of the Democratic coalition. Michelle Obama? Oprah? Michelle Kwan? The roster of the improbable and the ludicrous is long and will keep generating clickbait headlines until Biden unveils his pick.

While history suggests that blandness to the point of invisibility is not a political asset (does anyone remember Tim Kaine?), the virtues of surprise in the veepstakes are also overrated. One Sarah Palin or her equivalent in a lifetime is more than enough.

When Joe Biden makes his choice, my guess

is that he will go with competence and compatibility rather than a flair for

the dramatic. So with a deep awareness of the ease of being wrong, I’m guessing

that Amy Klobuchar will join Joe Biden with their arms raised high in triumph,

six feet apart, at the virtual Democratic convention.