In 2007, in the spring, after living in New York City for six months, I rode my bike from my university on the Upper East Side to a public health clinic for my annual HIV test. I’d had three sexual partners by that time, two women and a man; the man lingered heavy in my mind.

If I tested positive, that was that, I thought. My sex, ethnicity, age, and sexual behaviors would be added to a list and reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for surveillance. When I’d moved to France the year before, I’d had to show proof of a negative HIV test to be allowed a visa. The United States wasn’t any better in that respect: Testing HIV-positive also would have barred foreigners from entry into the U.S. back then.

I knew that from my best gay friend, an immigrant from Poland studying in my Ph.D. program in molecular biology. If he tested positive and gave his name, he could be removed from the country in the middle of his curriculum. He studied how the ear tunes itself to recognize different pitches. My work was on bacteria and the viruses that kill them.

HIV is a virus that copies its viral code into our DNA, sticking itself in us forever. Other viruses—like influenza, and like coronaviruses—come and go, eventually leaving nothing of their genetic material behind.

But our bodies do remember. When you meet a new virus, your immune system’s T-cells and B-cells respond by evolving to fight it. A part of this cellular response is the formation of antibodies, Y-shaped protein molecules that bind to the outside of a virus, blocking it from entering your cells, and target it for destruction. This is how vaccines work: They spur your body to generate antibodies to a virus you haven’t yet met. This is also how protective immunity works: Meet this novel coronavirus once, and survive, and your body will be able to fight it the next time without even getting sick.

In immunology, when antibodies against a virus or bacteria become detectable in your blood, “seroconversion” has occurred. This is a marker of having been infected by a virus. Seroconversion for HIV was once seen as a death sentence: It means you carry the virus and always will.

Seroconversion for SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes Covid-19, is more of a rebirth: It means you were exposed to the virus, fought it off, and are now likely immune—at least partially, at least for a time. (We don’t yet know how much protective immunity is conferred, but it would surprise immunologists and epidemiologists if there were none. The antibodies of recovered Covid-19 patients are being used as an experimental treatment for the currently ill.)

Testing everyone’s blood serum for antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, then, is a way to understand who’s still vulnerable to this virus. It’s also a way to understand who may not need to be locked down anymore. If seroconversion does confer immunity, then recovered antibody-carriers could safely go back to work—especially doctors, nurses, cab drivers, and transit employees. That gives crisis-mired governments an abiding interest in tracking who’s recovered and who’s not.

In order to free people from government stay-at-home and social distancing decrees, though, we would need a massive testing and serosorting system—perhaps even an “immunity passport” for those no longer vulnerable to the virus, as the U.K.’s health secretary suggested in early April, after testing positive for the coronavirus and emerging from self-quarantine.

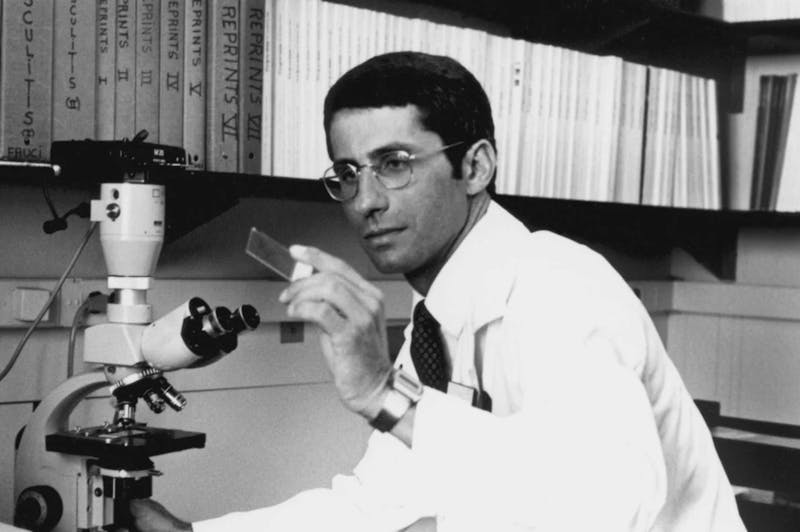

But a pandemic is not an excuse for authoritarian surveillance of our bodies and health. We know surveillance will impact vulnerable populations the most: Black and brown New Yorkers, infected with Covid-19 at the highest rates, would therefore be the most surveilled communities. The question becomes how to trace at-risk individuals and populations without inviting a police state. Looking to America’s HIV surveillance system—built by many public health officials, such as doctors Anthony Fauci and Deborah Birx, who now work on the White House’s coronavirus response task force—might show us how to handle this epidemiological challenge without ceding our bodily freedoms.

The city public health office smelled like cleaning solution. Light beamed in through the windows and reflected off the cheap white tile. It was one of the only places in New York in 2007 where I could get an anonymous test. I don’t know why this mattered to me. In order to get HIV meds, which would keep me alive, I’d end up on a list of the afflicted, anyway. But namelessness gave me a sense of agency: Whatever happened would happen to me alone, if only for a time. So I put my name at the top of the application sheet and checked the box for an anonymous test.

A nurse came in, and we chatted. I was anxious, but also, I’d always used condoms; I’d been as safe as I could.

“You put your name,” she said. “You can’t do that for an anonymous test.”

“Oh,” I said. “Sorry, I figured that information would be kept out of the system if I clicked anonymous.”

She sighed deeply. I’ve never wanted to be a burden on working folks. My right hand gripped my left tricep as I folded my chest into itself.

“So what do you want to do?” she asked.

“What do you mean?”

“If you want an anonymous test, you have to start over, take a new number, sit in the waiting room, fill out a new form.” I looked around the waiting room, empty except for me.

“Do you have any risky behavior?” she asked. “Unprotected sex?”

“Oh. No.”

“How many partners since your last HIV test?” she asked.

I paused. Why was she asking me this here, in front of everyone? But, looking around, I remembered that no one else was here. “Two.”

“And always safe? Every time?”

“Always.”

“Come on, honey, I think it’s going to be fine.”

I nodded, and she led me into a room to have my gums swabbed with a stick of paper, which would then be dipped in a solution, which would then turn a particular color if my spit contained antibody against HIV—a marker that I’d met the virus, that I was infected for good.

Testing SARS-CoV-2-positive, by this type of test, would theoretically be a marker of health, an (at least temporary) invulnerability to the virus that now perplexes the entire planet.

One explanation for why Covid-19 is so dangerous is that human immune systems haven’t met anything like it before. They first underreact, then overreact, a deadly path of disease. But as of this essay’s publication, some 700,000 people have been infected and recovered: a mere 0.009 percent of the planet’s inhabitants, a select few we believe to be invulnerable, a privileged survivorship that could theoretically help to save us all.

As sero-tests emerged in Germany, there were suggestions of the creation of a special identification card, an “immunity certificate,” for those who’d seroconverted. These people could safely ignore the lockdown to reenter the “normal” world of commerce, public safety, and constant contact. An editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine proposes a similar policy here: The immune could restart the economy.

A friend of mine who works as a nurse tested positive for Covid-19. He stayed at home and, like the majority of people who fall ill, felt better after a week and a half. He’s returned to work. I picture him riding the train now without worry, shopping without sanitizing every vegetable upon returning to his Brooklyn apartment.

“Threesome?” I half-jokingly asked him about joining me and my boyfriend in bed. “He’s the only safe person I know in New York,” I texted my boyfriend, an odd inversion of risk and seroconversion that I cannot quite fathom, even now.

We played this game with HIV for years, of course. In 2007, when a nurse called me into a small room and told me I was a presumptive positive for HIV and needed to have my blood drawn, I worried right away about the potential stigma: No one would ever touch me again, no one would fuck me, forget about love. Forget about love altogether; my life was beginning anew.

By 2019, the year SARS-CoV-2 emerged in humans, we knew how misguided our understanding of HIV seroconversion was. Now we have PrEP prescriptions, daily drugs you can take when you’re HIV-negative to prevent seroconversion even if you have riskier sex, like bottoming without a condom. We also know now that HIV-positive people who take drugs to control their infection cannot transmit the virus.

Seroconversion, a poz status, became a marker of safety. I’ve bottomed more than once for an HIV-positive man knowing that we were both taking drugs to thwart the virus, and so our sex was as safe as it could possibly be. And just as with HIV, serostatus says nothing about whether a person can transmit the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

HIV is also no longer a death sentence when people can actually access testing and care, an important lesson to apply to the Covid-19 crisis. It’s not just the virus that kills, but our inability to care for people with it. This is why HIV hit queer people and people of color so hard; this is why Covid-19 hot spots are now centering on black and brown neighborhoods in American cities.

Still, every single person who tests positive for HIV today ends up with their name on a list, reported to the state health department: seroconversion leading to a breakdown of doctor-patient confidentiality, state surveillance for the sake of the larger body politic’s overall health. An effort in the 1980s “to require states to send full name-linked AIDS case reports to the CDC provoked intense opposition,” U.S. public health researchers have written; since then, state HIV/AIDS info has to be encrypted and stripped of names before it’s forwarded to the CDC. Even so, fear of surveillance has affected how I—and many of my friends—have interacted with HIV testing for two decades now.

Once you’ve begun surveillance, it can be hard to undo and easy to abuse. More than half the states in America still have HIV criminalization laws on the books, with deadly consequences for minorities, the poor, and others with little access to health care or legal protections. Once a disease has been criminalized, it’s also more difficult to destigmatize. Fear of that stigma can discourage testing.

In the case of Covid-19, it’s clear that large-scale testing and surveillance both will be necessary for easing a total lockdown. In South Korea, which was the fastest-growing site of Covid-19 infections after China, the epidemic was stopped in its tracks by a massive surge in testing. But when someone tests positive in Korea, they must also go into quarantine. This directive is strictly enforced with the use of a GPS tracking app that alerts public health officials if the sick person leaves home. Close contacts of the confirmed positive Covid-19 individual are subject to quarantine, as well. What’s more, the Seoul government assigns all quarantined individuals a case worker (with two phone calls a day) and provides deliveries of food, along with instructions on how to take care of waste in the apartment.

Will Americans subject themselves to this level of government tracking and accountability? Will we tolerate phone tracking and individualized stay-at-home orders from the government—or, perhaps, from a subcontracted firm owned by a comically evil Trump-backing pro-surveillance billionaire who literally plans to live forever? (Maybe we can keep the care packages and leave the GPS tracing behind.)

My best guess is that if we don’t want the government to overreach, it’s on us to act for ourselves. The question isn’t whether we will contact trace, following individuals confirmed to have Covid-19 and mapping all their potentially infectious interactions. We will. The question is how we do it and ensure long-term privacy, especially if serosorting is needed for a time, until we have a good vaccine or PrEP-style preventative medicine for Covid-19. Trump is clearly using this crisis to do exactly what he always wanted to do, not what’s needed for public health. Governmental surveillance has seeped into Americans’ lives quietly for decades now.

Quarantine must be a care-minded, voluntary system that comes with the resources we know people will need in order to ensure their voluntary compliance—including “measures to provide job security and income replacement to meet the basic needs of individuals in quarantine,” as two researchers put it more than a decade ago. Epidemiologists tell us this will work. How do we know? From HIV, from tuberculosis, from Ebola, from the diseases that came before.

My name did not end up on a list in 2007. My second test (a finger prick) and my third (a blood draw) both came back negative for antibodies to HIV. I walked out of the clinic. I cried in my Polish friend’s arms, again, this time for relief, for joy. He held my hand. I was still negative. I wasn’t like them. I didn’t have this virus, one that I still thought would kill me.

I look that thought in the face, and I’m ashamed to have had it. I hated the HIV-positive version of myself then, a version of the person I might well become. That is no longer the case.

Until a decade ago, the U.S. remained one of about a dozen countries in the world that barred entry to people with HIV. That discriminatory practice was only reversed in 2009 by the Obama administration. The lists are still kept, the names and information still reported, but at least our serostatus can no longer be used to make decisions about our fitness to visit the homeland.

We cannot let fear drive our response to Covid-19—not fear of the virus, of the infected, or of government. Good governance and community care are the only things that can save us now, that can coordinate the type of massive response we need to manage diagnostic testing, medical supply chains, epidemiology, drug and vaccine development.

There are lessons to be learned from the HIV era. Personal information must be held only in local health departments in highly secure databases in a way that’s de-identified but not anonymized. This means that an individual could be found by local health officials if needed—if their particular virus was found in transmission again, for example. New York City doctors would be able to contact trace and voluntarily quarantine people who test positive for the virus after this current surge of cases wanes.

There is no reason to report names—as opposed to demographics—to the federal government. Especially this federal government. And there’s no reason to keep any of this information forever.

One tool that could help us all stay healthy would be to rapidly staff doctors’ offices, hospitals, stores, and restaurants with the immune—if they’re truly immune. Someday, we hope, that immunity can come from a vaccine that’s free and available to all. But until then, serosorting (but not sero-surveillance) may save lives. The Covid-19 seropositive may soon stand up to this virus, safely. I put my faith in them and promise, for my part, to ensure they’re safe from stigma, persecution, and being named on a list at the CDC.

I’ve spent years trying to de-serosort my own mind—to not value a human, me or anyone else, by the presence or absence of an IgA, IgM, IgG in their body. HIV that’s still in us, a coronavirus come and gone. A virus wants nothing. The presence or absence of a virus in a person doesn’t make them good or bad.

We must protect the most vulnerable among us from this virus, yes, but also from each other; from our government; from all the harm we can do with our fears. Will we let fear lead, track the Covid-19 positive with phones, and send the cops if they move? Or will we encourage people to do the right thing and support them with all they need to survive until they emerge from their apartments, healthy again and seroconverted? We must watch ourselves to avoid being watched; we must care for each other to avoid being policed.