It was one of the biggest days in the history of Point Reyes Books. On Saturday, March 14, it had “holiday-level sales,” said Stephen Sparks, who has owned and operated the Marin County, California–based independent bookstore since 2017. “We were up 350 percent.”

But Sparks wasn’t celebrating. “Bookstores are places where people browse and touch everything,” he said. “It’s a small space with everyone is shoulder to shoulder.” That evening he made the difficult decision to close the store to the public, starting on Monday. “Financially it was a very hard decision to make,” he said. “But ethically it felt like the only one we could make.”

In the end, the choice was out of Sparks’s hands. That Monday, California Governor Gavin Newsom issued a shelter-in-place order for six Bay Area counties, including Marin. Since then Sparks has kept his business afloat fulfilling online orders. It’s “twice the amount of work,” he said, “because every book needs to be packed up and shipped” and only brings in “half the amount of money.”

He is, however, allowing a few people in. During our phone call Sparks stepped outside so one of his regulars, an 80-year-old man who comes in “three or four times a week,” could browse the store alone, safely.

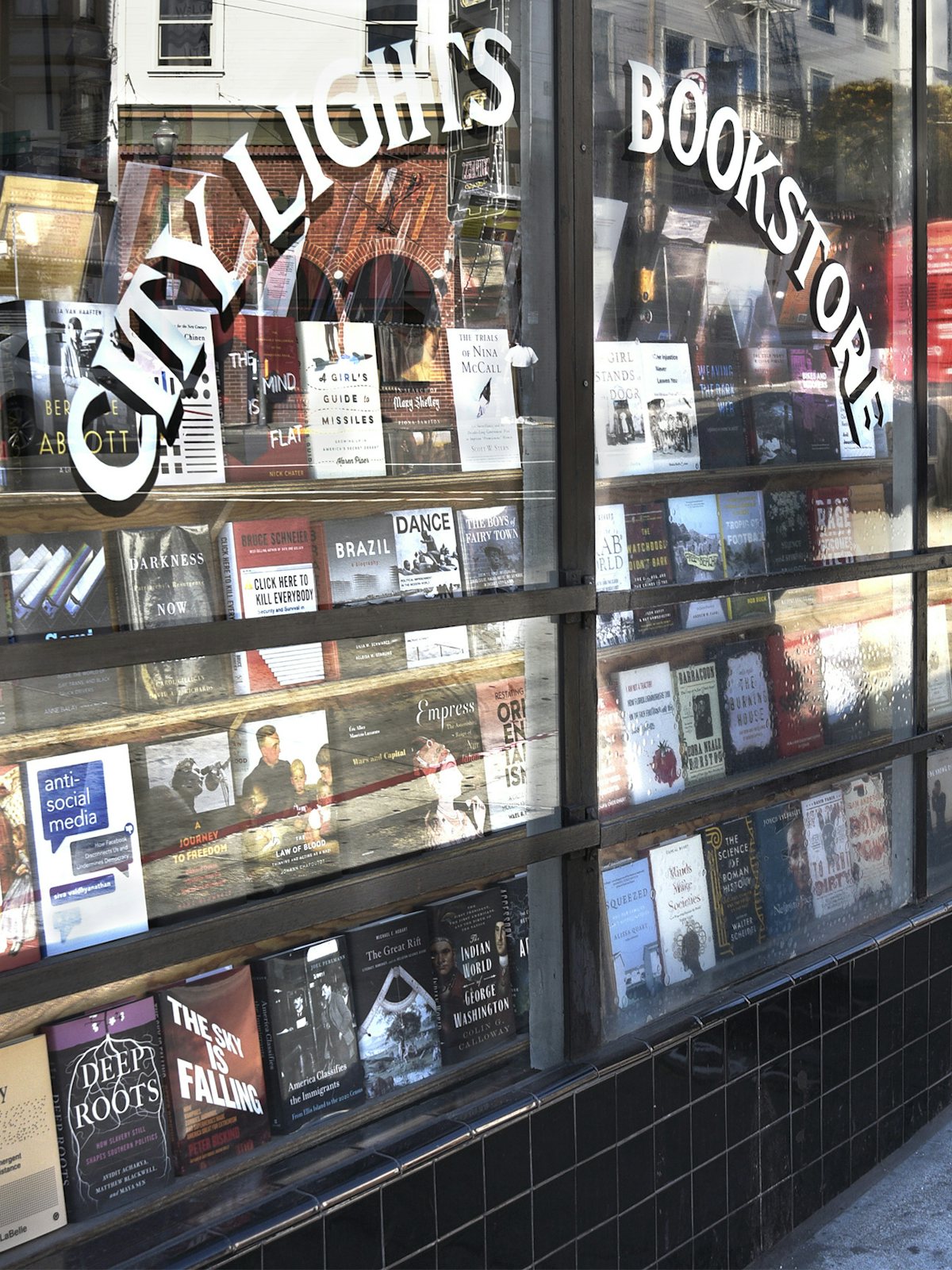

Across the country, thousands of small bookstores are in the same predicament. Closed to the public, many are rapidly shifting into the unknown territory of online sales. Those with little to no web presence have no revenue at all. Large indies like Powell’s, The Strand, and McNally Jackson have laid off hundreds of workers. City Lights, the legendary San Francisco bookstore, has turned to crowdfunding, as have smaller stores.

What’s clear to everyone is that the much celebrated “independent bookstore renaissance,” which coincided with the post–Great Recession economic expansion, is over. Hundreds of stores may never reopen again. The future of independent bookselling, a tenuous, low-margin business in the best of times, has never been gloomier.

The indie renaissance followed a mass extinction. The rise of superstores like Barnes & Noble and Borders in the 1980s and ’90s was a disaster for smaller shops, which lacked the chains’ inventory and ability to offer steep discounts. Customers were also moving away from downtown, locally owned businesses and doing their shopping at malls. In the seven years before the Great Recession began, more than 1,000 independent bookstores closed.

When the recession struck in 2008, bookstores were barely hanging on. Those that had weathered fights against big-box stores now faced the rise of Amazon. By 2011, even the superstores were struggling as Amazon increasingly became Americans’ bookseller of choice; that year Borders filed for bankruptcy, closing 400 stores and laying off thousands.

In the scorched aftermath of all this creative destruction, a rebirth occurred. According to the American Bookseller Association, there was a 49 percent growth in the number of stores between 2009 and 2019. This dramatic comeback is typically discussed in moral terms, as if consumers had a re-awakening after years of shopping in soulless, over–air-conditioned bookstores that all looked and felt exactly the same.

A Harvard Business School study published by Ryan L. Raffaelli earlier this year said independent bookstores enjoyed three distinct advantages: They fostered a sense of community between business and consumer; their wares were curated specifically for their clientele; and they were places where people could physically convene. These were not just stores selling widgets, they were local hubs.

Furthermore, despite stocking books from a heavily consolidated publishing industry dominated by five massive corporations, they were downright artisanal. In a “bowling alone” era with few genuine communal spaces, bookstores were a rare gathering point. They were also retail environments where customers and employees were encouraged to interact—where, even in large cities like New York, you could get to know employees.

The indie renaissance was also an outgrowth of gentrification. With people flocking to cities—and with malls turning into the retail equivalent of elephant graveyards—bookstores popped up, many aided by cheap rents from municipalities hoping to spur growth. Book publishers, looking for a leg up against Amazon’s faceless behemoth, were keen to tap into those relationships, pushing authors to participate in indie events.

Now, like many small businesses, bookstores are on life support. Closed to the public, they can’t do the thing that they do best: bring people together. Some are still holding events on Zoom, but they lack the commercial and cultural benefits of in-person events. (There is a sense in the industry that the streaming events are a waste of time, requiring a fair amount of labor for little reward.) “I don’t know if we’re going to have an event again for another year,” Sparks told me. “We’re not a bookstore that’s reliant on events to stay open like so many are—for them it’s going to be particularly tough.”

Many are rapidly transitioning to online retail. “We effectively now are a fulfillment center,” said Brad Johnson, owner of Oakland, California’s East Bay Booksellers. “We’re learning. We’re better at it than we were three works ago. Some of those early orders I’m sure we completely mangled. Some days are overwhelming, some days you feel like you get a handle on it. It’s pretty monotonous. It doesn’t really resemble at all what we were doing.”

Tom Roberge, who owns the Providence, Rhode Island–based Riffraff, talked to me while waiting to hear from a web designer. In lieu of a functional online store, he has been taking orders via email. Approximating the in-person experience is key, he claimed. “You process every single order yourself, you thank everyone effusively,” Roberge said. “You do everything you can to let your customers know you appreciate it—all those little things. I don’t want to make it out like I’m doing some community service but people being able to email a business and talk to somebody—even if it’s just email—and interact when they’re otherwise just shut up in their apartments? That is valuable.”

The emergence of Bookshop.org, a new website that connects independent bookstores with consumers, has been a boon to many stores without online shopping capabilities. “There are almost 2,000 bookstores in the country and only 150 of them have good online shopping platforms,” Andy Hunter, the company’s CEO, told Inside Hook. “That leaves a lot of stores that haven’t adapted and Amazon’s kind of eating their lunch.” Stores that participate collect 30 percent of profits, about two-thirds of what they would receive selling directly to consumers.

For stores without online shopping capabilities, these are particularly dire times. Last week, City Lights, which does not do internet sales and has been closed since March 18, turned to GoFundMe. It raised more than $450,000, a figure that CEO Elaine Katzenberger told me still might not be enough. The store has to “build a bridge to get us to the place where we could have some capital to pay the bills that are coming due,” she said. “There is some relief happening but it’s temporary. We still have to pay for things that are coming due. We haven’t furloughed employees, so there’s wages and health care.” Raising money “was an attempt to stabilize us while we hope to access to whatever federal and local funds become available—and those aren’t guaranteed to become available.”

At any rate, independent bookstores cannot survive as full-time fulfillment centers. Although many saw a sales boost during the first two weeks of home confinement, it has since petered out. Online sales may become an important revenue stream for the industry, but they can’t replace in-person sales.

Even if the economy were to reopen in the next couple of months, there would likely be serious aftershocks. Things will certainly not go “back to normal” immediately. Millions are unemployed and a recession is inevitable. When state governments approve the reopening of restaurants and businesses, it’s likely that many people will be wary about spending time in crowds, cutting into the slim margins of independent bookstores.

The industry is already changing dramatically. The booksellers and publishing industry employees I spoke to expressed concern about the viability of nearly every 2020 release, with one marketing manager at a major house describing it as a potential “lost year.” Because of the upcoming election, publishers had stacked the spring and early summer with big releases. Now, many of those have been delayed until the fall, when media coverage will be overwhelmed by politics.

The impact of store closures and release delays could be devastating for fiction, in particular. Adult fiction sales, which are heavily dependent on retail stores, were already in free fall, declining 20 percent over the last five years.

And, though Amazon has received a raft of negative press over its abysmal treatment of workers during the coronavirus crisis, it will likely emerge even stronger.

After the demise of Borders, with Amazon growing ever more powerful, publishers strengthened their ties with independent stores, papering over their many differences and disagreements. Those relationships have grown strained because of the coronavirus. Penguin Random House was applauded for the way it has recently treated struggling bookstores, offering 60- and 90-day payment extensions on their books; HarperCollins was also praised by the booksellers I spoke to. But their rivals have not been so generous: Simon & Schuster and Hachette have offered little in the way of a helping hand—a slight that many bookstore owners told me they wouldn’t forget. (Simon & Schuster is currently for sale. Hachette is under pressure to produce profits—one explanation for its aborted attempt to publish Woody Allen’s memoir.)

The relationship between stores and their employees may also change. Bookselling has always been a low-wage business, and bookstore owners in New York and California have treated minimum wage increases, paid time-off bills, and unionization as an existential threat. When the economy closed down, many bookstores laid off employees without “waiting for the ink to dry” on shelter-in-place orders, according to one recently fired bookseller.

Powell’s, the celebrated store in Portland, Oregon, laid off hundreds of employees via email last month, with little warning. “You think of Powell’s as this family-owned bookstore,” one recently laid-off employee told me. “There’s this misconception that they treat their employees like family. But the way they handled this was extremely corporate.” Online orders allowed Powell’s to rehire some of them, but even this effort was mishandled—many of these rehired people were managers brought on to do union work.

“They fucked over a lot of people,” said the former employee, who asked to remain anonymous so as not to jeopardize their chance of being rehired. “A lot of my coworkers had been there for 30-plus years. People’s health insurance was tied to the company. Everyone was panicking. They did everything so late in the game that everyone was screwed.”

Booksellers are increasingly demanding more of their employers. Unionization is on the rise. Despite being heralded as a calling, bookselling is just as precarious and low-paid as other retail work. Despite being told by shop owners that they were all in this together, hundreds of booksellers were laid off at the first sign of trouble.

Some people told me they hoped that, if the industry survives (and that’s a big if), long overdue changes would follow. “I have been of the firm belief that much of the growth of independent bookselling has been at the expense of the health of independent bookselling,” Johnson of East Bay told me. “A lot of it has been unsustainable. A lot of it has been manipulative and has been emotionally and psychologically abusive to its workers.”

RiffRaff’s Roberge was even blunter: “If you’re going to wear your values on your sleeve, you have to fucking back it up. I think a lot of what is happening is that people are being exposed, right?”

The rosy coverage of the independent bookstore renaissance overlooked unseemly aspects of the bookselling trade that are now coming to the fore. But those are questions for another day. Over the course of our conversation, Stephen Sparks of Point Reyes packed books. “I don’t have time to think about anything else,” he said.