I currently live in Salt Lake City, but I’m originally from the New Mexico side of the Navajo Nation and still have cultural connections and citizen connections there—I’m still voting there. There are coronavirus outbreaks there now, in my small community of Naschitti, but I wasn’t there when I caught it. It’s likely that I was exposed when I was traveling in early March on a business trip from Salt Lake to Washington, D.C., and New York City.

I flew back to Salt Lake on March 8 and went into the office that week, all regular hours. I went to my workout and did everything I normally do routine-wise. After my workout, I came home and I felt ill. I was feeling it in my throat. I had body aches in my lower back, a neck ache. Then it started going into fever. And then body chills, and then I started coughing a dry cough. Later, I started to get the tightness in my chest.

I was concerned, so I started going through the Covid-19 hotline in Utah, and that hotline was just a mess. It was just not available or responsive. The hotline referred me to Intermountain Health Care in Salt Lake City, which referred me to ConnectCare, an app where you can talk to providers over the phone or FaceTime. I tried to get through there but couldn’t because it was overloaded. There were at least 10 people ahead of me each time. And each time I had to pay a $60 co-pay just to talk to a provider, even though I never got to talk to one.

The next day, I remember waking up chilly and heated. I was like, shit, I’m scared—not even just scared, but the anxiety of it was like, What is it that I have?

My friend told me I should go get screened or ask for a test. I first called the local Indian Health Service center here in Salt Lake City, Sacred Circle Healthcare. It’s run by the Goshute Tribe. I told them my symptoms and that I had just traveled from an outbreak zone. I was referred by them to go to Intermountain headquarters in Murray, Utah. They said that was where most of the screening and testing was happening. So I went there. They referred me to the visitor emergency room and gave me a mask.

In the E.R., they checked my vitals. The provider, I think he was a physician’s assistant, he said, “I know you have the symptoms, and I want to test you, but I can’t. The health department in Utah won’t give me their approval.” And at that point, I didn’t know there was a lab issue, I didn’t know there was a shortage of tests. I was frustrated—do I have to be a member of the Utah Jazz to get tested? I was pleading. I said, “Health care is a basic human right.” He said, “Not in America.”

I had a breakdown in the emergency room. We’re in a pandemic, how can you not test me? I was really frustrated and distraught and upset. A friend at that point called me, and I just broke when she was talking to me. This infrastructure isn’t ready for it, and then you’re denying people like me from getting tested. I did everything. I called the hotline. I called the ConnectCare app. There was no way I’m going to get through this.

I got a number from the University of Utah Health to contact them for possible testing through their system. They promised me, at that time, that they could test me and that I shouldn’t be denied testing. At that point, I was so frustrated. A nurse said she would have a provider call me and go from there.

I slept again and woke up drenched, again. By day three, the University of Utah called me and said, “We can’t test you because you weren’t exposed to a known Covid-19 case.” And I’m like, “How am I going to get tested? I was in an outbreak zone, there are so many cases there.”

Between day one and day 13, Salt Lake had earthquakes. I was just lying there on that Saturday. That was my first earthquake, I didn’t know what to do. Everything was shaking.

I want to go back to New Mexico to be with my family, but I can’t. I communicate with them daily. At this point, I had told my parents I was sick. They were like, “Just come home,” and I have to tell them that I can’t do that—this is contagious. I tell them to stay home. They were upset that I was in this situation. Out of love. My mom was like, “I keep telling you guys you need to take care of yourself, but you don’t listen.”

I FaceTimed her during that period. I was bedridden. I was sweating. I thought maybe I had pneumonia. I’ve never felt this sick before. Usually it’s the stomach flu, and it’s two to three days and I’m over it. But this was totally different. I’ve never sweated like that. She broke down on me when she saw me, and I broke down with her. She’s just being a mom, being concerned for me. I love her. She keeps up with me daily.

After the first five days, I started to feel better. My temperature started to go down. I started cleaning my apartment, started cooking. By the time day 13 arrived, more tests had come through, and that’s when the CDC relaxed its guidelines for testing, so more testing and labs were available. That Monday, I was alerted that the University of Utah’s lab was testing 1,500 people per day, so I felt this was a chance to see what I have. By that time, I still had a sensitive chest and the dry cough. I called in to the University of Utah, talked to the provider. I waited a long time to get through. Luckily the physician’s assistant gave me the order to get tested. I got screened that day. Same as the flu, they stick that Q-tip in your nose. And they were nervous because I had that order, but they were just looking at me because my symptoms had largely subsided. But I had my order. Give me the test. I did the drive-through, the whole protocol. At the end of it, I tested positive for Covid-19.

I’ve been drinking sage. And while my family never came up, I know that they prayed for me and had ceremony. I really appreciate that and love that they cared for me in that spiritual realm. I’m privileged to come from that knowledge system.

Years ago, I went to New York because I wanted to get educated in a city like that. But I got carried away with the ambience of the city and did forget what got me to New York. The beauty and teachings of Navajo. The rain. The dirt. The canyons. But I had to go on this journey to realize what I have and where I’m from. My intuition now is saying, You have to go home after all this is over. Build my own home, from my own hands. Garden. I want to focus on my family, on foundations, on ceremony. I want to focus on eating healthier and planting foods and being more self-sufficient. Execute those goals on a larger scale. And then reintegrate back into society on Navajo, because our people right now need our help more than ever.

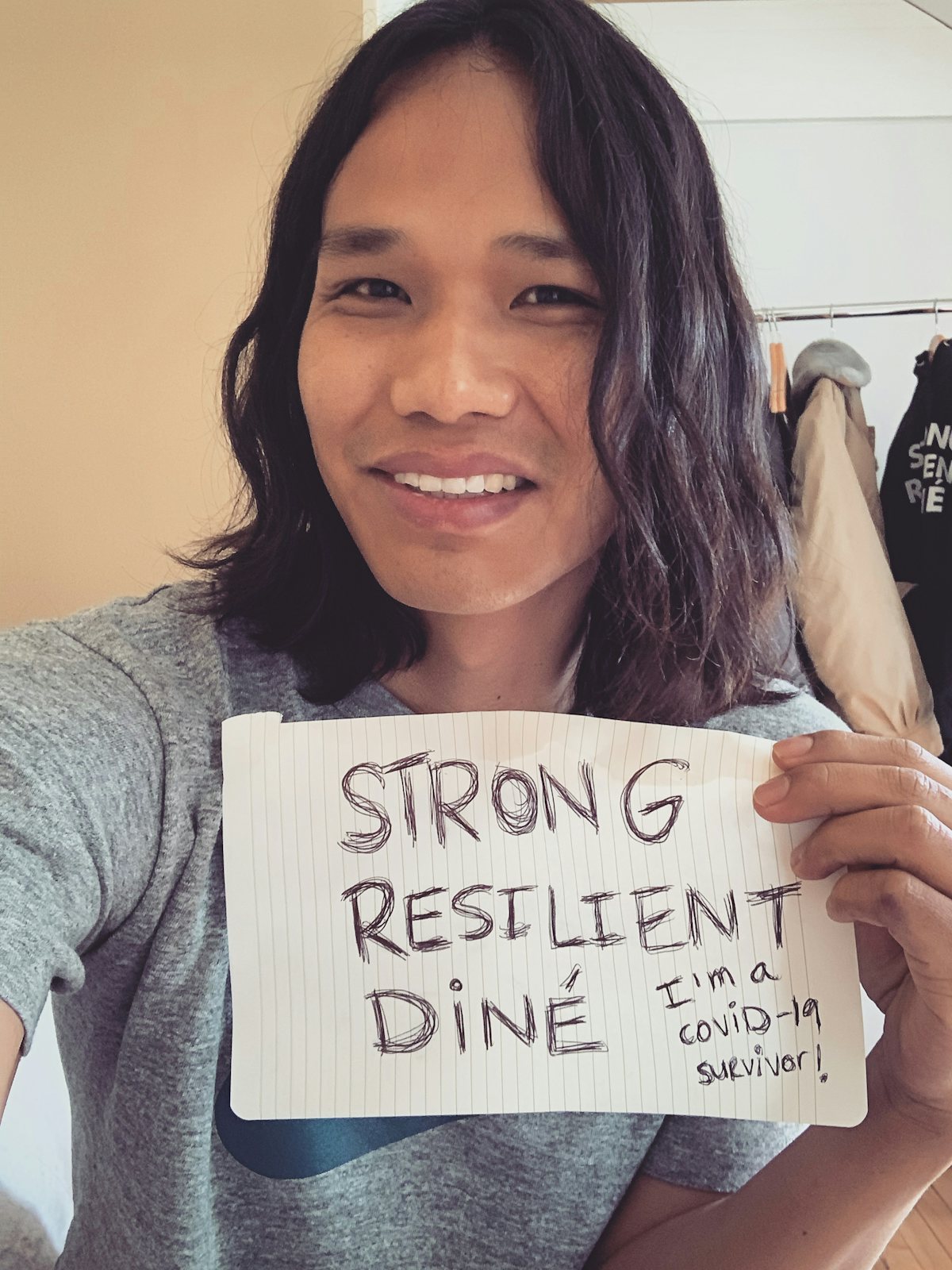

In spite of what we face as Native American peoples, we will still be resilient, even in this pandemic. That’s what I’ve been taught. It’s called sihasin in the Navajo language. You never lose hope.