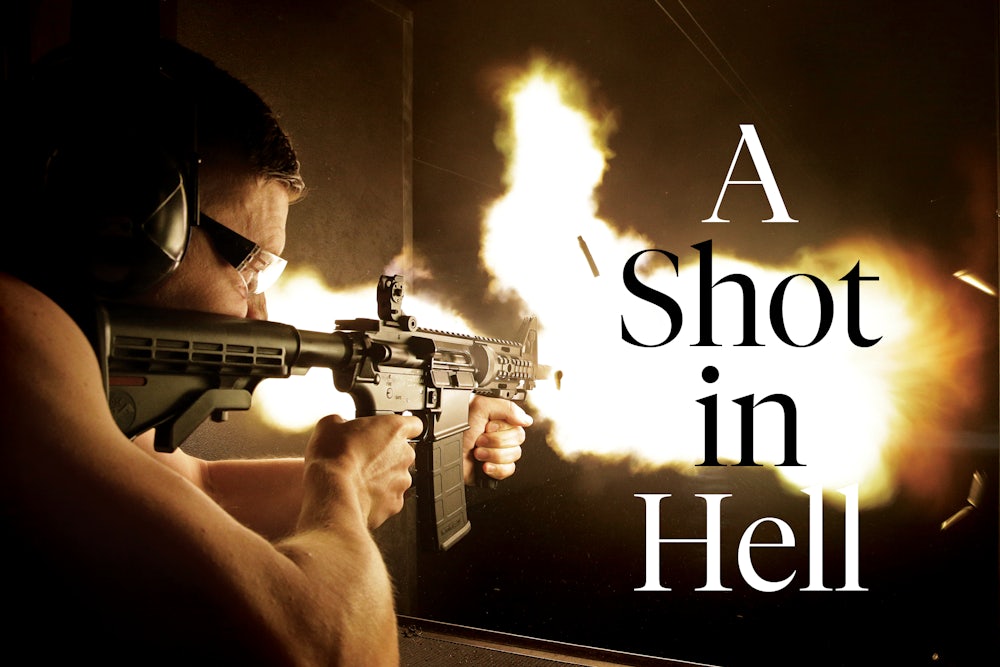

I had been in Las Vegas for two days before I looked up the site of the deadliest mass shooting in American history and realized that it had occurred in the open lot across the boulevard from my hotel. On October 1, 2017, just after country star Jason Aldean took the stage for a finale at the annual Route 91 Harvest music festival, a 64-year-old man armed with 22 military-pattern semiautomatic rifles fired 1,100 rounds into the concert grounds from an upper floor of the nearby Mandalay Bay hotel, as audience members ducked for cover or ran in terror. Semiautomatic guns fire a single round with every pull of the trigger. To increase the rate of fire on the 14 AR-15s he was using, all of which he’d purchased legally, the killer affixed “bumpstock” attachments to them. This accessory enables a shooter to “bumpfire” a semiauto rifle, meaning that every time you depress the trigger, the weapon’s natural recoil from firing pushes the trigger back against your finger and causes the weapon to fire again—a deadly perpetual motion that simulates a machine gun’s “fully automatic” action. In 10 minutes, the shooter killed 58 concertgoers and injured more than 500, before he shot himself in the head with a revolver.

In the three years since the Las Vegas Strip massacre, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) has broadened its definition of machine guns—which in the United States have been regulated into scarcity—to include these “bump-stock–type devices,” mandating that anyone in possession of such a device must have surrendered or destroyed it by March 26, 2019. But Sin City, where pot is legal and people can walk the street with alcoholic beverages in to-go cups, remains “a haven of machine gun tourism,” as Bebe Noyes—a.k.a. Machine Gun Bebe—told me when I visited Machine Guns Vegas, where Noyes works as a gun restorer and range safety officer. Regulations have not and will not prevent machine-gun enthusiasts or the merely machine-gun curious from dropping hundreds of dollars at special ranges to fire these weapons, including those no mere civilian would ordinarily have the opportunity to touch. Major joints include Bullets and Burgers, Gunship Helicopters, The Vegas Machine Gun Experience, and Battlefield Vegas.

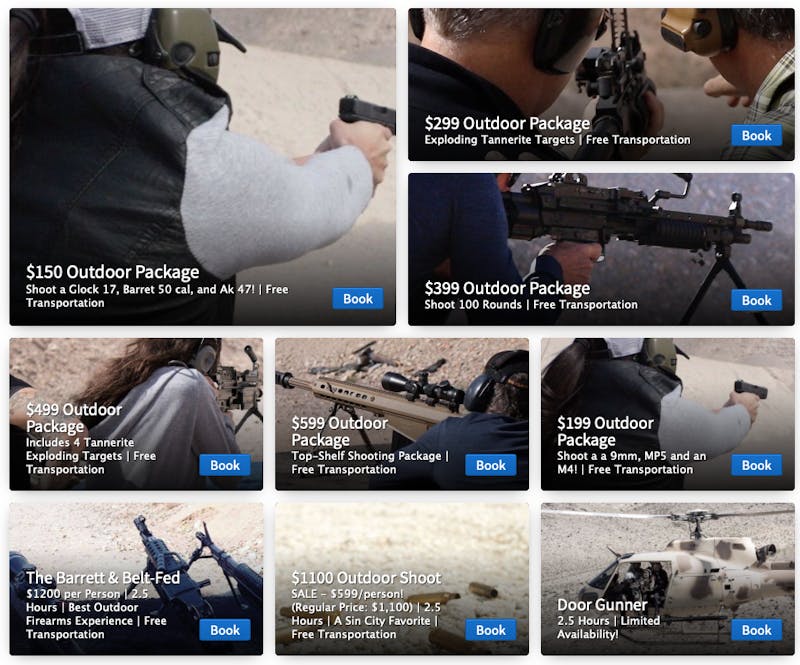

Machine Guns Vegas, which caters to gun novices with package deals tailored to specific demographics, is one of the oldest and best-known. There’s the “Femme Fatale Experience,” in which you can shoot off pink M4s and MP5s for around an hour for $110, and “The Gamers Experience,” which includes full auto assault rifles that are ubiquitous in virtual first-person–shooter games ($190). Vegas being Vegas, MGV also offers a “Shotgun Wedding” deal ($690), as well as a “Brass and Ass” bachelor party promotion ($180 per person) that after the shooting takes your entourage to a nearby strip club. The $499 “Just Divorced” experience, exclusively for women shooters, bills itself as “the only way to celebrate your freedom from the ball and chain.”

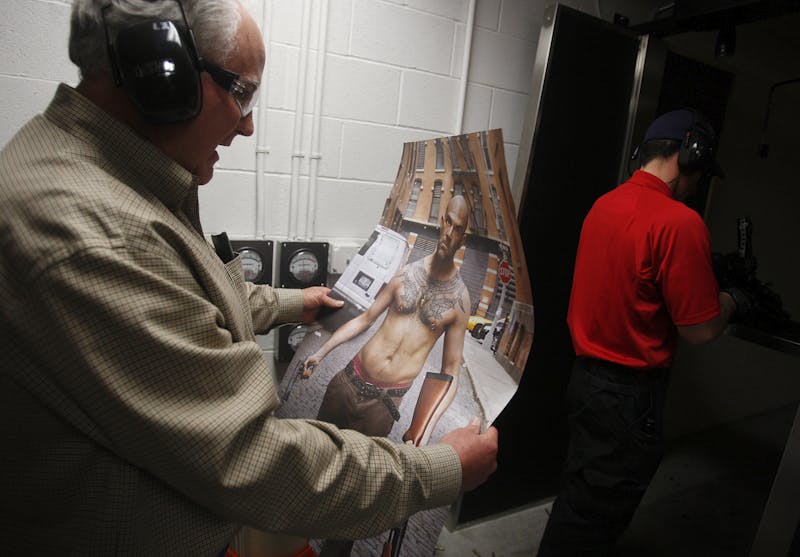

The Machine Guns Vegas indoor range is a gray box, squat and nondescript. Inside, the music is loud and the vibe suggestive of a bro-heavy sports bar, except for the intimidating panoply of weapons spotlighted on the brick walls and the swag shop selling pithy T-shirts. A jacketed rifle round is captioned JUST THE TIP, I PROMISE. For the ladies, there’s a tank top that reads GUNS AND ROSÉ. Beyond that, on another table, MGV-branded shot glasses are laid out for sale, including some designed to look like shotgun shells. The check-in desk is graced by a large sign: GUESTS WHO HAVE CONSUMED ALCOHOL WILL NOT BE PERMITTED ON RANGE—NO EXCEPTIONS.

“A lot of people ask, ‘Do you serve liquor?’” Genesis Del Sol, one of the staff, told me, laughing and rolling her eyes as she took my driver’s license and verified my reservation. Del Sol, it turned out, was from Miami, not too far from where I grew up, but firearms were not a part of her life in the Gunshine State. “I knew nothing about this before, never thought I’d own a gun. Now I have an AR-9,” she said, referring to a pistol-style variation on the AR-15 that fires 9mm handgun ammunition, as the muffled sound of full-automatic fire drifted back to us from the sealed range behind her. “Do you want a paparazzi?” she asked as she handed me safety glasses and ear protectors. “Someone to take pictures of you with your phone out there,” she clarified. I smiled and declined.

I had come for the discount “Full Auto Experience”: For $299, you can choose six machine guns to fire from a selection of 12, including a fully automatic Glock pistol (“As seen in Skyfall,” Machine Guns Vegas’s website announces); an AK-47; several variants of the AR-15’s rapid-fire military cousin, the M4 carbine; and the infamous Israeli Uzi submachine gun. As it happens, I’m the son and grandson of gunsmiths; I have been shooting since I was seven years old and writing, with some internal conflict, about firearms culture for a decade and a half. But I had never live-fired a machine gun before, rare as they were, and I was curious what the experience might tell me.

Liberals tend to recoil at the idea of guns as recreation—and to blame increasing gun violence on the ease of accessing such entertainments. I couldn’t help wondering whether the opposite were true. Would taking certain firearms off the streets and putting them exclusively on specialty ranges satisfy Americans’ curiosity and gun-lust while saving us from carnage? People who might otherwise engage in harmful behavior could even find some catharsis. A heavily regulated machine-gun amusement park like this one, I reasoned, might be the very future liberals want for military-pattern assault weapons.

Most of the people I meet, including those with firearms experience, are surprised to learn that machine guns are legal to own in the United States. It’s an easy mistake to make, considering how few there are. More people in the United States probably die from semiautomatic gunfire in any given month than have died from machine gun fire since Franklin D. Roosevelt was president. Of an estimated 393 million firearms in the United States in 2017, only 638,260 were machine guns, according to the ATF—and the ATF knows, because each of those full-automatic weapons is logged in its national registry. In fact, the story of the machine gun in America is that of a rigorous, thoughtful, evolving set of regulations that has largely worked.

The story begins in 1934, five years after Al Capone’s St. Valentine’s Day Massacre and one year after an Italian-American bricklayer unsuccessfully tried to shoot Roosevelt during an appearance in Miami. That March, bank robber John Dillinger—a fan of Thompson submachine guns, like Capone—escaped from prison, spurring a national manhunt. Widespread unease about lawlessness spurred Congress into action. Representative Robert Doughton, a long-serving Democrat from North Carolina, introduced the National Firearms Act as a curative. “For some time this country has been at the mercy of the gangsters, racketeers, and professional criminals,” Doughton said, before the act passed on a voice vote. “The rapidity with which they can go across State lines has become a real menace to the law-abiding people of this country.”

The law, which Roosevelt signed in June 1934, targeted gangland weapons—not just machine guns, but also easily concealed short-barreled shotguns and rifles, as well as firearms silencers. It could have gone further; it was originally written to include more common firearms, but, Doughton said, his colleagues on the Ways and Means Committee felt “that the ordinary, law-abiding citizen who feels that a pistol or a revolver is essential in his home for the protection of himself and his family should not be classed with criminals, racketeers, and gangsters.” (Exempting handguns also eased resistance from the nascent gun lobby; during a brief debate on the NFA, Democratic Representative Samuel Hill of Washington noted tersely that “the National Rifle Association approves” of the bill.)

The NFA didn’t ban machine guns outright, as some states subsequently did—but it made them nearly impossible to obtain, especially if you weren’t squeaky clean. To remain legal, every full-auto gun now had to be serial numbered and registered with federal revenue agents. They could only be sold by or through federally licensed dealers, and each transfer had to be accompanied by a $200 federal tax payment, what would be nearly $4,000 today. In the 1930s, the fee doubled the cost of a new tommy gun. The expense, and the government registration requirements, were steep enough to scare off most would-be buyers. Overnight, the market for machine guns shrank to police, military forces, well-heeled collectors, and virtually nobody else.

The system was far from perfect. If, say, you had inherited a previously unregistered machine gun and tried to register it with the federal government, revenue agents could share that information with state authorities, who could arrest you for breaking state laws. That practice was found to violate an individual’s Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination in 1968; it was remedied in Congress the same year by a landmark Gun Control Act, which simply barred Americans from registering machine guns that were already in their possession but unregistered.

The closest thing to an outright federal ban on fully automatic firearms was signed into law by Ronald Reagan in 1986. On its face, that legislation—the Firearm Owners’ Protection Act—was intended to loosen restrictions on mail-order gun sales and prevent investigative abuses by the ATF. But before the bill moved on to the Senate, a Democratic congressman from New Jersey, William Hughes, tacked on an amendment that barred individuals from possessing any machine gun, unless it was legally registered prior to the act.

Even with the amendment, the Senate overwhelmingly passed the measure with bipartisan support. There was little popular enthusiasm for machine-gun ownership, and there was a sense that the 1934 ban needed more teeth: During the Cold War, American and Soviet allies had glutted the globe with literal tons of M16s and AK-47s in their respective ideological struggles for geopolitical dominance, and the cocaine trade had generated an interest in the weapons among well-capitalized drug lords. The $200 transfer fee had also never been raised, and it was no longer the deterrent that it had been half a century earlier.

As a result of the 1986 law, the only legal machine guns in America—“transferable arms,” as they’re known in the industry—are those that had already been legally registered before the act went into effect. As time went on, increased scarcity drove up the prices of these “pre-’86” transferable arms; by one estimate, a tommy gun appreciated in value from $9,000 in 2004 to $27,000 in 2017, far outpacing the gains of the Dow Jones Industrial Average and even the value of gold. In a legal market like that, the main buyers were very dedicated collectors, profit-seeking investors, and specialty ranges like Machine Guns Vegas, where, for a few hundred dollars, I could drop in, shoot more than $100,000 in ammo-spitting weapons in an hour, and leave with a couple of memories.

“We do not do any training here,” Machine Gun Bebe told me before I went in for my hour of shooting. “We are purely entertainment and recreation.” An Army veteran who runs MGV’s outdoor range, where you can plink at steel gongs (or blow up a car filled with Tannerite explosives) with an M249 Squad Automatic Weapon from the door of a moving helicopter, Bebe Noyes estimated that 90 percent of her business is people who have never fired a gun before, most of them foreign tourists from Asia and Europe—“a lot of folks from Hong Kong, Shanghai, Beijing, Paris, London, ze Germans, et cetera.” The customer base fluctuates with exchange rates, but the customer experience remains constant: “We don’t sign our guests up for the NRA,” Noyes said. “We don’t push a new sort of ideology. We just give them a chance to enjoy historical and modern weapons in a safe nonpolitical environment.”

Politics notwithstanding, it takes a lot to make that environment safe. In 2014, an instructor at a similar full-auto shop over the border in Arizona was killed by a single shot to the head when the nine-year-old girl he was coaching lost control of an Uzi. A viral video of the moments leading up to the incident spurred legislators nationwide to consider new regulations regarding machine guns and minors, but few ideas became law.

Specialty ranges, however, are like airlines: Their business depends on minimizing dangers and learning from past tragedies. After the Arizona death, MGV experimented with a line barrier on the range to prevent muzzles from rising dangerously high when they’re fired. Rather than adopting it, MGV now opts for the close physical involvement of the range safety officer with the shooter. “First-time shooters are kind of like horses, where the farther away you are from a horse, the more room it has to kick you,” Noyes explained. “We’re practically wrapped around the first-time shooter—not literally—but we don’t give him a lot of run.”

Which is not to say machine-gun tourism doesn’t attract some knowledgeable shooters—or at least virtual shooters. “People in the gun industry kill me when I say this, I’m going to say it anyway: Video games pumped so much new blood into our industry with a comprehensive appreciation for historic and new-model weapons,” Noyes said. “We’ll get kids in here, 12, 13 years old, and they’re like, ‘I want a P90.’” She was referring to a futuristic-looking Belgian “bullpup” submachine gun that is featured in dozens of video game franchises, from Call of Duty and Medal of Honor to Rainbow Six and Grand Theft Auto. This was an interesting point: For decades, the NRA has blamed pop culture, video games, and movies for gun violence; but movies and video games have always featured a lot of full-auto gunning, and America’s ceaseless massacres do not. A cultural fetish for certain firearms, while formidable, doesn’t seem to translate into actual violence unless those firearms are also readily available to violent people.

I felt as if I were in a video game as I entered the firing range behind my safety officer, Kim Alvarez, a short 21-year-old who used to work at Jack in the Box. After opening a cage locker and pulling out an M249 SAW that seemed almost as big as her, she cycled the gun’s action as expertly as any Marine machine gunner I’ve met. MGV staffers used to go for lunch at the restaurant where Alvarez worked, and eventually they recruited her. She started as an entry-level loader, cleaning the used weapons and carefully piecing together linked ammunition for belt-fed guns like the SAW. “I was 17,” she said, as she laid out my first gun, a Glock pistol modified to shoot 20 rounds in a few seconds with one pull of the trigger.

“You want to aim low on the target with that one,” she advised. She loaded the gun, cycled the action, and handed it over to me. I squeezed the trigger of the pistol, as I have countless times in my life, and it responded with a defiance I had not experienced, the muzzle trying to fly up with each round I loosed. Just as I was getting a feel for the kick, the ammunition ran out. “Not bad,” Alvarez said. She pulled the paper target in for inspection. From a mere 15 feet or so, my 20 rounds had crept up the length of the target, with no identifiable grouping. Still, I had placed all my shots somewhere in the target, and Alvarez said that made me an above-average shooter.

I tried the MP5 submachine gun, a favorite of police around the world. Then came the Draco, an AK-47–patterned machine pistol, whose recoil made an impression in my shoulder that lasted for three days. I sampled a Saiga full-auto shotgun, which was surprisingly easy to aim and fire; a SAW, which I was grateful not to have to clean after the session; and the “Noisy Cricket,” a comically shortened variation on the military M4. (“It’s like the M4 and Draco had a baby,” Del Sol had told me earlier.) I can’t speak for others, but the usual pleasures that I derive from shooting sports—being outdoors, learning the arms’ mechanical workings, clearing my mind with a relaxed focus on the target—weren’t present at the range. Machine guns offer neither Zen nor hunting prowess. They’re relentlessly loud and powerful until they run out of ammunition, which doesn’t take long. Wielding that kind of noise and violence is either fun to you or it isn’t. For most seekers of a Vegas full-auto “experience,” an hour is enough experience for a lifetime.

Having fired AR-15s for two decades, I felt weird standing around while a diminutive attendant loaded the weapon and cycled the charging handle for me. But by any measure of safety, it was much harder to make a fatal mistake on this firing line than on any conventional range. “We provide a Disneyland excursion for our guests,” Noyes had boasted. The line conjured childhood memories of plinking away in a Frontierland shooting gallery as I adjusted my just-bought coonskin hat. As then, there was only so much damage you could do here. For all the weapons’ force and din, machine-gun tourism felt like the theme-park revival of a celebrated but culturally dead practice.

Could shooting ranges be the future of Bushmasters, of SKS rifles and AR-15s and AR-10s? It seems the thought experiment we need in Second Amendment debates, where pro-gun advocates warn that federal ownership registries and licensing are the sine qua non of government tyranny. Yet the United States has successfully depleted the supply of machine guns, as well as the ease and attractiveness of their use by criminals, with exactly these measures: a gun database and a thoroughgoing application process. (That said, the left should be as wary as libertarians—perhaps more so these days—of the potential risks that gun registries run as a tool of discrimination and harassment; one need not sympathize, as some on the gun right do, with David Koresh and the Branch Davidians to acknowledge that the ATF has abused its oversight powers before.)

But compared to regulating the types of semiauto rifles that have grown popular in mass shootings, the machine-gun regulatory blueprint also seems quaint today. As gun proponents never tire of pointing out, it’s much easier to define a class of “machine guns” than it is to define “assault weapons.” One formidable argument for the ineffectiveness of the Clinton era’s ban on assault weapons was that it defined those guns largely by cosmetic modifications or accessorizing—pistol grips, folding stocks, bayonet lugs—so that near-identical guns, with identical ammunition and mechanical capabilities, were exempt from the ban. Even “machine guns” get redefined as arms technology and tastes evolve. The bumpfire episode shows that before the Las Vegas shooting and the eventual ban of these accessories, the ATF was issuing insurance letters to bumpstock-makers that guaranteed their products were legal “firearm parts” and didn’t qualify as NFA weapons.

A more significant challenge to restricting semiautomatic weapons is that there are simply too many AR- and AK-style firearms in the United States, with ever more being brought to market—far more such weapons than there ever were machine guns in the country. When machine guns were banned, revulsion against them and the violence they wrought was already a consensus social norm. Because of their cost and the carnage they sowed, they were seen almost exclusively as the province of armies and gangsters. They never became, as the AR-15 has become, an instrument of sport or a revered totem of freedom and self-reliance.

In any case, the thought experiment may actually need to run in reverse: We may need to consider what America would look like if machine guns were more readily available. The explosion in popularity—and the cultural significance—of AR-15s as a civic talisman is also a symptom of a more malignant pro-gun segment of the conservative movement. Ever since the election of Barack Obama fueled appetites for anti-government conspiracy theories, this new breed of gun fundamentalist has eagerly embraced a belief in “constitutional carry,” an innovative dogma that insists citizens have a Second Amendment right to carry any weaponry anywhere, without training or licensing. Unsurprisingly, in this atmosphere, machine guns—preferred by gangsters, effectively banned by a stroke of Ronald Reagan’s pen, and consistently considered taboo by most Americans—now have more advocates than ever.

Grassroots gun organizations, which have tacked steadily to the NRA’s right on a variety of firearms policies, now argue for repeal of the 1934 National Firearms Act and the 1986 Hughes Amendment. On the day Donald Trump was inaugurated as president, someone created a petition exhorting the White House to consider repealing the NFA “in order to remove regulations on our 2nd amendment rights, increase national economic strength, and provide protection against threats to our national security.” It needed 100,000 signatures within 30 days to be forwarded to the White House; it got 250,000. Trump appears to have ignored the plea, but another 60,000 signatures have been added since.

In this hypercharged gun culture, not even Machine Guns Vegas is immune from charges of being gun-grabbing pinkos. “We were the only range that closed after the October shooting,” Megan Fazio, the MGV publicist, told me. “Obviously everyone is super pro-Second Amendment here, but we all had friends who were impacted.” In a press release the day after the Vegas shooting, the range announced a two-day closure “out of respect for the injured, lives lost and families affected by this senseless act.” It also made donations to a local blood center and a GoFundMe for the shooting victims. For that act, Fazio said, the range was pilloried by hard-core pro-gun activists. One line in the statement made pro-gun advocates especially irate: “We believe, as we always have, that there should be more stringent control on the types of firearms private individuals can own and the processes they must go through in order to own those firearms.”

Two days later, by the time a popular pro-gun blog put Machine Guns Vegas on blast for its “gun control” advocacy, the release had disappeared from the range’s website. But the blog’s angry commenters knew what was up: The range, they said, was run by a “buncha libs.” “Repeal the NFA,” one commenter wrote. “If they make a peaceful return of our rights impossible, they will make a violent return inevitable.”