Since he could say the word, my son has been obsessed with the subject of microbes. At his insistence we have a library of children’s literature on the subject, books such as Meet Bacteria!, Inside Your Insides, and a particularly unsettling work about parasites called What’s Eating You? The fact remains that at 8 p.m. on a Tuesday night I do not want to read about microbes. I want to read the story about a beached whale that is a metaphor for loss and death. “No,” he says, and because he is a child enamored of precision, “read me Tiny Creatures: The World of Microbes.” So I do. “All over the earth,” I read, “all the time, tiny microbes are eating and eating, and splitting and splitting, changing one thing into another.”

He refuses to interrogate his obsession (being five), so I can only speculate as to why this might be captivating. Children’s lives are full of imagined worlds, but this one, the books insist, is real. He is blanketed in tiny animals no one can see, creatures more diverse than all the plants and animals in the visible world, protecting his skin and digesting his dinner and making a home of his inner ear. Access to this secret world blows his little mind, but only so long as it is secret. He is only interested in biology up to the point of visibility. You have never seen a small child so bored at the zoo.

All my life I have been shielded from the consequences of our carelessness. It has been easy not to see. It takes intention to think that a vote could translate into, say, hundreds of thousands of Iraqi deaths because these deaths happen outside our borders, and as most Americans know, what happens outside of our borders is not real. It is not real when an Italian family puts on hazmat gear to get a last look at a dying parent through a glass window. It is not real when China transforms work spaces into quarantine camps. It is somehow not even real when this happens in Seattle (so long as you’re not actually in Seattle).

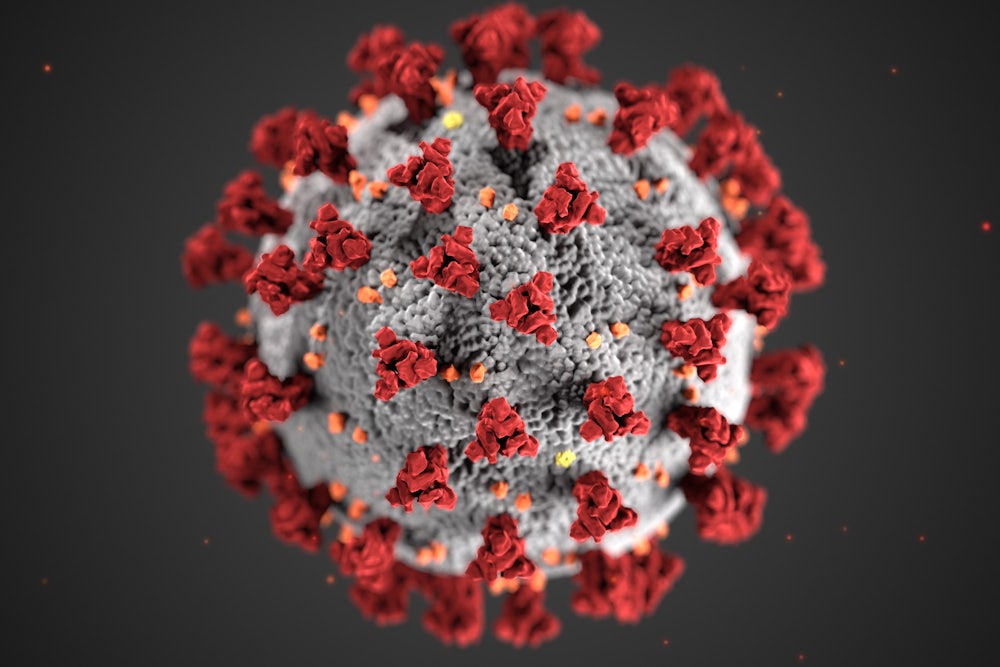

In January a spiked sphere multiplied itself using the cells of people from China to South Korea and Thailand and the Northwest of the United States. After Wuhan was walled, after the World Health Organization declared an emergency, we continued to go to conferences and boarded cruise ships and not think about the harmless spherical Staphylococcus aureus we exhaled in vibrant microbial clouds. Four hundred of my Iowan neighbors and I packed into a high school auditorium to debate the Democratic nominee and did not try to imagine the rods of Propionibacterium slithering around on our shared pens. By March it was inevitable that many Americans would simply lose the ability to breathe, and the man in charge said we should change nothing about the way we live. There are not nearly enough tests or beds or masks, which means that this time, we will not have to work to see that we have been careless. “Inside you,” I read, “where they are warm and well fed, they split and split and split until just a few germs have turned into thousands, then millions.”

It’s not as if grifters will not ask us, in other domains, to see what isn’t there. In the void of information surrounding our intelligence agencies, they project a deep state. Into a maelstrom of economic disruption, they project Mexicans. But isn’t this true story the story of which a xenophobic demagogue dreams? Covid-19 is literally a foreign invader that threatens the elderly, his dependable voting base. It renders the openness of liberalism a liability; Chicago is now just as dangerous as rural Republicans have long wanted to believe it to be. In June, the president was criticized for using the verb “infest” to describe immigration. We castigated this man for building a dumb, useless wall until we begged him to advise us to make fortresses of our homes. This is not how I thought any of this would happen, but you will never predict the future by projecting ideological consistency.

“Because microbes are so good at making more microbes,” I read, “some of the things they do are very, very big.” The person who loves my son most in the world, outside of this house, is a 65-year-old respiratory therapist working in a hospital 1,042 miles away. “I hope they’re keeping the older medical staff away from quarantined patients,” I text my mother. “Too late,” she texts back. At work she dons double protective gear and stands at the bedside of someone who exhales the spiky spheres. It is thus impossible for me to read Tiny Creatures: The World of Microbes without wondering what I will say to my son if my mother dies. Some of the things they do are very, very big. This would elevate our conversation from the invisible to the visible world, of course, and so I suspect his eyes would lose their cast of wonder. He would look back to the illustration of the feverishly multiplying microbes. He would simply pretend not to hear.