There are a few reasons you might not want to watch a movie about an infectious disease right now. The most obvious is instinctive: Why walk into a fictional, trivializing version of one’s own distress? Besides, the news channels are giving movies a run for their money these days. On Thursday, for example, the head of pulmonology at a hospital in Bergamo, Italy, told The New York Times that his colleagues are being forced to “draw a line on the ground to divide the clean part of the hospital from the dirty one.” The line between good and bad, creeping down an Italian hospital hallway: It’s just too simple and evocative to be true. And yet there it is in the newspaper.

The coronavirus disaster is messing with the boundary between fantasy and reality, leaving us feeling somewhat fictional ourselves, adrift in the enormity of the crisis and the volume of surreal information before us. What pandemic cinema offers is not an escape, exactly, but a refreshing variety of ways to frame or process that information.

What these movies have that real life lacks is pacing. Steven Soderbergh’s snappy Contagion, from 2011, opens with a title card reading “DAY 2,” leaving us wondering for the rest of the movie about the day we missed, while frantic pressure accompanies the spread of the MEV1 virus. Gwyneth Paltrow dies foaming at the mouth, and drums beat along to the action. Meanwhile, scientists hunt for the origin of the disease, tracing it back through time to look for an antidote.

In real life, living through a disaster means long periods of uncertainty and boredom, which is difficult to reflect in a movie meant to entertain. This note of falseness also affects traditionally paced thrillers like Outbreak (1995), about the spread of an Ebola-like virus, and the 2013 South Korean movie Flu, about an illness that breaks out in the city of Bungdam, near Seoul. Both of these movies also feature strong elements of romantic comedy, as pairs of lead actors (Dustin Hoffman and Rene Russo, Jang Hyuk and Soo Ae) race to save one another against an almost incidental backdrop of deadly disease.

All three are entertaining, because the pandemic is a good device for showcasing ordinary people sacrificing themselves, and hanging the earth’s future in the balance. A virus, though invisible, is also a way to illuminate the systems, real or imagined, that invisibly govern our lives. Contagion contains some really fascinating information on the spread of viruses that everybody knows now anyway. Outbreak shows the U.S. military outright bombing a village in Zaire in order to contain an illness. In Flu, the president of South Korea gets temporarily overthrown by an evil official from the World Health Organization—a plot point with resonance for a country with fraught relations with global organizations like the International Monetary Fund.

None of these movies rely too heavily on the bodies of unwell people for the effect of their horror, instead making villains out of those who oppress the vulnerable: bad bureaucrats, military men played by Donald Sutherland, etc. In this way, they are distinct from zombie thrillers, which are usually premised on the spread of some zombie-making disease. Still, they are equivalent in the sense that everybody ends up dead. In the zombie-virus movie Patient Zero, Stanley Tucci plays a professor of medieval philosophy who is teaching Augustine’s doctrine of love when he gets bitten. He grows to be superintelligent as well as monstrously violent, explaining to surviving humans that they are evolutionarily defunct because they believe in love—Augustine’s criterion for being a human.

In Patient Zero the reason for the outbreak is society’s collective anger, stoked by “feminists” and “conservatives” and “freaks” among other factions, an orange-eyed Tucci explains. In other movies, the sin sublimated into devastation is war. In The Andromeda Strain, hailing all the way from 1971, the residents of a rural American village drop dead, their blood inexplicably turned to powder. The armed forces round up a group of expert scientists to work on a solution in a deep, multilevel bunker hidden under a building labeled “Agricultural Center.” They discover that the outbreak is the result of “germ warfare.”

The Omega Man, also from 1971, is another movie about American guilt. Charlton Heston thinks he is the last man alive, single-handedly preserving “civilization” against the infected masses from his stylish L.A. apartment. The infected call themselves “The Family” and rail against modern technology, dressing in monkish robes and decrying “the stink of oil and electric circuitry.” In their view, science and weapons and art have destroyed mankind, and only the cleansing destruction of the sickness can save it. It’s hard to know whose side to take.

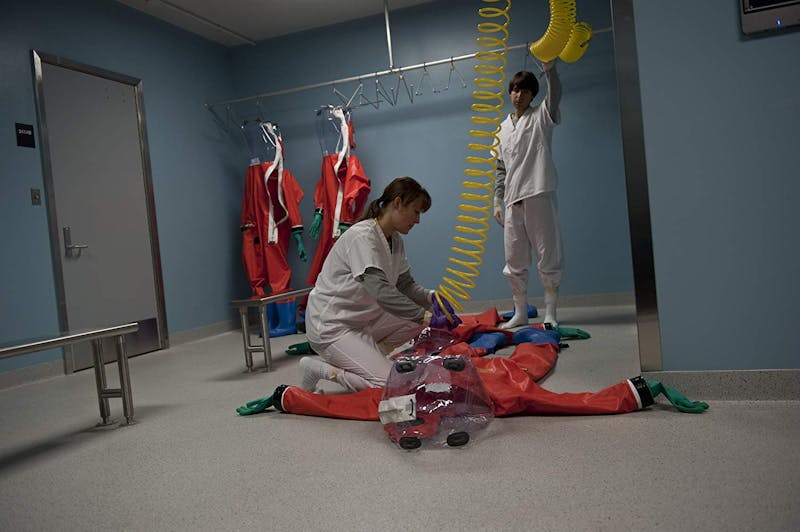

Where the atom bomb and war in Vietnam were the crises to which The Omega Man and The Andromeda Strain responded, Outbreak, Contagion, and Flu work through different problems. In these films, military officials and medical personnel come into angry confrontation with each other, prompting debates about the virtues of sacrificing the few for the survival of the many. The problem is that military and political strongmen cannot or will not understand the science of the crises facing them, which is really a failure of communication. Procedural problems around the spread of disease become the locus of a struggle for power that must be resolved justly in order for the movie to conclude; no laboratory in the world can make that happen, only language and mutual trust.

The other side of the coronavirus coin is isolation. Movies about viral pandemics and zombies are sprawling stories that traverse entire countries, continents, planets. They imagine a world out of all physical control. Movies about isolation and containment also obsess over losing control but from a diametrically opposite angle, placing their characters in an existential quarantine that troubles the edges of their sanity.

The nightmare version of isolation is the closed-room horror movie: Cube, Saw, Quarantine, Fermat’s Room. The dread that accompanies locked rooms feels familiar, since it’s the same one that trails us around our apartments in isolation, asking us if we’re sure we’re not about to lose it. In psychological terms, those gory slasher flicks are inheritors to classic films of containment and domestic tension, such as Hitchcock’s Rear Window and Polanski’s Repulsion. In films like these, an apartment or other limited space becomes a microcosm for the world, simultaneously showing us a tiny stage and a vast symbolic space.

Isolation is the situation that most of us in fact find ourselves in, for now, while we try to dodge this disease. While we wait, we can’t be afraid of fiction that reflects the circumstances we are in. Even when they’re frightening, as Contagion undoubtedly is, movies about pandemics and isolation are acts of imagination that refuse to accept that reality has a monopoly on illness or despair, horror or pain.