The coronavirus pandemic—and the Trump administration’s failed response to it—dominated Sunday night’s debate between former Vice President Joe Biden and Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders. But one of the debate’s more intriguing moments came during a discussion about something that didn’t call panic to mind: Women and their potential role in the two candidates’ administrations.

“I commit that if I’m elected president and have an opportunity to appoint someone to the court, I’ll appoint the first black woman to the court,” vowed Biden. “Secondly, if I’m elected president, my Cabinet, my administration will look like the country. And I commit that I’ll pick a woman to be vice president. There are a number of women who are qualified to be president tomorrow; I would pick a woman to be my vice president.”

This isn’t the first time Biden has made this promise; he offered similar guarantees in February. But the promise carries new weight at this point in the race. Barring a late surge by Sanders, he appears set to capture the Democratic presidential nomination in the next few months. (Whether or not Biden has a Supreme Court choice locked and loaded, it’s possible that, at this point, he already has his choice for running mate in mind.) Some have criticized Biden’s pledge on various grounds. But what Biden is committing to do is nothing new in American history. What’s more, it may actually be an essential move for Biden to make after the Trump era, in order to ensure the federal judiciary actually resembles the people who come before it every day.

Obviously, I'm not a Democrat, but I find it borderline disqualifying to commit to a gender or racial test for any appointment.

— Gregg Nunziata (@greggnunziata) March 16, 2020

BREAKING:

— Charlie Kirk (@charliekirk11) March 16, 2020

Joe Biden just committed that his running mate "will be a woman"

He also committed to appoint the "first black woman to the Supreme Court"

What happened to qualifications & experience?

This is identity politics at its worst

Shameful!

Biden's promise to appoint a black female to the Court is a remarkable moment for the presidency. It is saying that there will be a race and gender prerequisite for appointments to the Court. This follows the pledge in the earlier debate to impose a litmus test on nominees.

— Jonathan Turley (@JonathanTurley) March 16, 2020

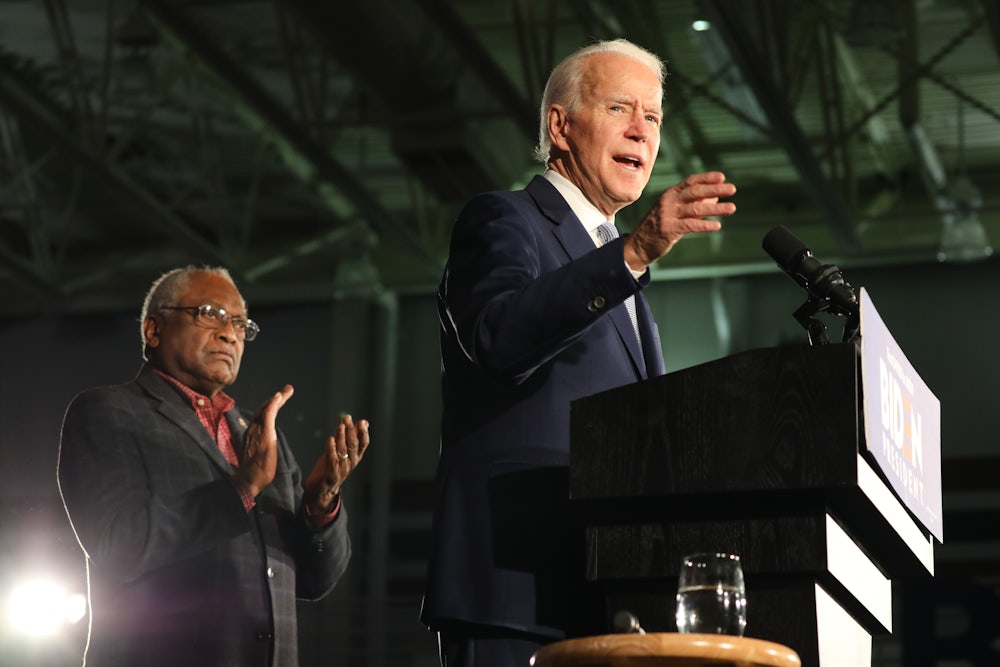

It’s not unusual for presidents to take race and gender into account when making significant appointments. Such choices are part of coalition-building in a diverse nation. African American women, for example, form the electoral core of today’s Democratic Party. South Carolina Representative Jim Clyburn, whose endorsement buoyed Biden ahead of his pivotal victory last month in the state’s primary, argued that whoever wins the Democratic primary should choose a black woman as their running mate.

“I really believe that we’ve reached a point in this country where African American women need to be rewarded for the loyalty that they’ve given to this party,” he told NPR last week. “So I would really be pushing for an African American female to go on the ticket.” Among the names Clyburn floated were Stacey Abrams, who narrowly lost Georgia’s last gubernatorial election, and California Senator Kamala Harris, who endorsed Biden last week.

Biden himself arguably benefited from this way of thinking, albeit the other way around. In 2008, the then-senator from Delaware had ended his presidential bid after coming in fifth place in the Iowa caucus. Had Barack Obama not chosen him to be his running mate later that year, Biden likely would’ve been destined to be an elder statesman in the Senate. But Obama chose Biden for two reasons: to add a measure of foreign policy experience to the ticket and to strengthen his standing with working-class white voters.

The Supreme Court is not designed to be a representative body, of course. And an occasional critique leveled against conscious efforts to diversify the court is meritocracy: that potential justices should be chosen for their legal acumen and judicial temperament. That’s undoubtedly the most important quality for a president to consider. The mistake is assuming that it can only be found in a limited set of people. There are more than 600 serving federal judges, along with hundreds of others in the state courts. There are also a few thousand law professors in universities across the country. Would they all make good justices? Probably not. But a healthy share of them would do well. Judicial excellence is not so hard to find in America.

These presidential calculations are nothing new, either. Dwight Eisenhower picked William Brennan in 1956 to appeal to Irish Catholics and Democrats in the Northeast ahead of that year’s presidential election. He also told aides that he wanted to appoint a chief justice who would “create geographic and religious balance on the court,” eventually naming California’s Earl Warren to the seat. The two men would lead a progressive revolution on the high court over the following 15 years. Lyndon B. Johnson even engineered the resignation of a sitting Supreme Court justice so he could appoint Thurgood Marshall as the first black justice to replace him in 1967.

Nor are explicit campaign pledges to nominate justices who meet certain characteristics all that unusual. In 1980, Ronald Reagan pledged to nominate the first woman to sit on the Supreme Court. He fulfilled that promise by nominating Sandra Day O’Connor the following year. Donald Trump has not made any such promises of his own. He campaigned in 2016 on appointing justices “in the mold of Antonin Scalia,” who died earlier that year. But even he may be unable to resist the temptation: It’s widely believed that Amy Coney Barrett, a rising conservative jurist on the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, would be nominated to replace Ruth Bader Ginsburg if she retires under a Republican president.

Indeed, Trump’s approach to the judiciary is anything but diverse. Through him, the conservative judicial-confirmation machine placed 51 young conservative judges on the federal appellate courts—roughly one-quarter of the total number—as well as more than 100 in the district courts. A recent New York Times analysis found that two-thirds of Trump’s judicial nominees were white men, effectively reversing Obama’s efforts to create a more diverse judiciary during his eight years in office.

Trump’s Supreme Court nominees also fit that model, though the choice of Neil Gorsuch elevated the first Protestant to the court in a decade and added a rare Westerner to the bench. The next Democratic president, whether it’s Joe Biden or someone else, will need to take conscious steps to ensure America’s federal judges resemble the America they serve. Imagining Supreme Court nominees whose diversity extends only from Georgetown Preparatory School’s class of 1983 to its class of 1985 will not be enough.