One Christmas, I bought my parents compact-fluorescent light bulbs and a copy of Global Warming: A Greenpeace Guide. It was 1990: I was proud of my job at Greenpeace U.K., on the climate team, and the task of explaining to my puzzled family that the planet was in crisis seemed as urgent as the one we faced at work every day, trying to convince the British public. The question of how to tackle climate change—chain ourselves to backhoe loaders? Kick-start a solar revolution?—was one that tore Greenpeace apart internally. Eventually, I moved on to a different life, to New York City and motherhood, funneling my green politics into the purchase of a Toyota Prius and chlorine-free toilet paper.

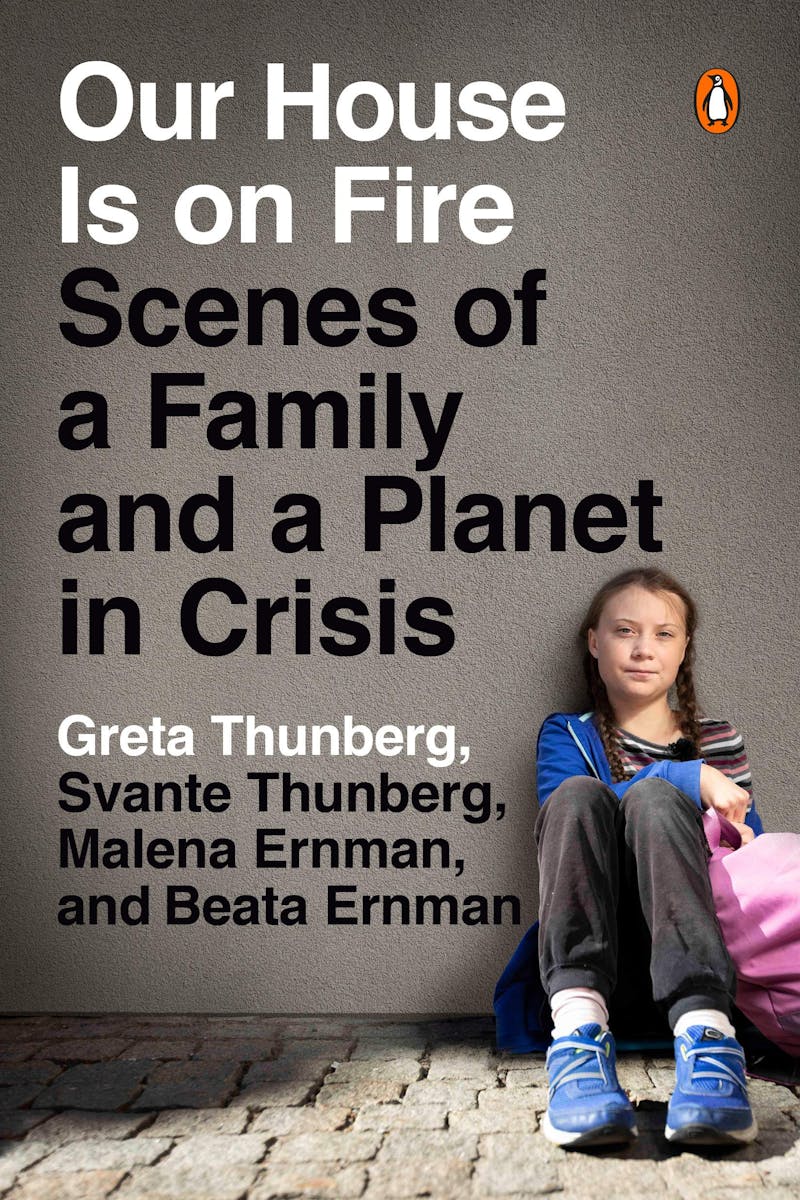

The first time I heard Greta Thunberg’s voice, last September, the impact on me was visceral. She’d sailed the Atlantic to berate Congress for its inaction on climate change, landing just yards from where I then worked, at a magazine in Battery Park. I took my 11-year-old daughter, Caroline, to hear her speak. “Our house is on fire,” Greta said, her high Pippi Longstocking tones surprisingly clear and confident in the bracing seaport air.

She was doing what we’d failed to do, 30 years ago. She’d found an action—her simple act of skipping school to sit outside the Swedish parliament—and a language to make people listen. We’d all been dozing, and she was shaking us awake.

Our House Is On Fire: Scenes of a Family and a Planet in Crisis tells the story of the years leading up to Greta’s School Strike. It’s “voiced” by her mother, Malena Ernman, but written by her whole family: Greta; her younger sister, Beata; their father, Svante; and Malena. The result feels like a new form of nonfiction, intimate and approachable as a photo album: a family memoir.

Malena was an acclaimed opera singer before she dropped everything to focus on the crisis of the book’s title. A language of music and stagecraft pervades the whole book, which unfolds in a series of “Scenes”—pithy episodes from the life of the family, dense with metaphors of song.

When she was 11, Greta stopped eating. She also stopped laughing or speaking to anyone except the immediate family. The account of Malena and Svante’s struggle to find help and to feed her, one tiny mouthful of rice or avocado at a time, is acutely painful to read. Nothing works. One day, as Greta nears the point of needing hospitalization, the family, in a desperate bid for domestic jollity, bakes cinnamon buns together. They dance and sing as they put them in the oven, but then Greta is unable to eat a single bite. Her parents scream: “Eat! You have to eat, don’t you understand?! You have to eat now, otherwise you’ll die!”

Eventually, Greta is diagnosed, with Aspergers and OCD. It emerges she’s been bullied mercilessly at school for years, that other kids have mocked and attacked her for her social oddity (she does not like to say “hello”). Watching a film at school about ocean pollution, too, has caused her deep trauma, and she’s unable to shake it off as other kids do. “She belonged to the tiny minority,” writes Malena, “who could see our CO2 emissions with their naked eye. Not literally of course, but still. She saw the invisible, colourless, scentless, soundless abyss that our generation has chosen to ignore; the greenhouse gases streaming out of our chimneys.”

Greta can’t do the self-protective trick the rest of us perform—a cognitive dissonance that allows us to know the glaciers are melting and carry on as though we don’t. Her unswerving gaze reminds me of the French philosopher Simone Weil, who also starved herself. For Greta, though, activism is a path to recovery. Alighting on the idea of her climate strike, she gradually starts eating again and embarks on a phenomenal drive to educate herself. At a meeting with climate scientists, she startles her father by speaking aloud.

One of the things she learns is that the world’s richest 10 percent account for half of all greenhouse gas emissions. “People,” in other words, are not the problem: People like Malena and Svante—and so many of us in the developed world—are. To their immense credit, Greta’s parents join her on this new pilgrimage, committing to a low-carbon lifestyle and renouncing air travel. It’s a huge change for Malena, whose professional life involved zipping from Vienna to Paris to Berlin. A Wagnerian note enters her description of her final flight: “the jet engines sang the monotonous song that plays a unique minor role in the liberation of the tundra’s greenhouse gases from their 100,000-year permafrost sleep. The awakening of the mighty methane dragon.”

The book intertwines issues facing young women with the health of the planet: In the West, Malena writes with crisp authority, climate change is expressing itself in the rise of “stress disorders, isolation and growing waiting lists within paediatric and adolescent psychiatry.” Yet she insists on reclaiming her own diagnosis of ADHD—which she discovers after almost collapsing under the weight of family stress—as a “superpower,” inextricable from her musical gift.

Beata shares that gift, and the diagnosis. As her parents focus on Greta, neglecting her, Beata withdraws, and then, as Malena describes with rueful candor, one day erupts. “‘You are the worst bloody mother in the whole world, you bloody fucking bitch,’ she screams as Jasper the Penguin hits me on the forehead.”

Beata is obsessed with the British girl band Little Mix, and one of the most poignant episodes in the book is when Svante, determined to keep a promise he’s made despite the family ban on air travel, embarks on a five-day drive with her in their electric car to see the band in London. Beata blares pop music all the way there and stays in her hotel room when Svante goes sightseeing; on the way back, in line at a McDonald’s outside Hamburg, Svante breaks down and weeps. “Surrounded by 50 billion lorries, motorways and BMWs, he realizes that it doesn’t matter how many electric cars we acquire,” Malena tells us. But his grief seems personal. For years, he and Malena have fought—to access medical care for their daughters; to catch each girl, in turn, as she falls—and in this pause by the side of the highway, the hugeness of their task overwhelms him.

Yet this is also a remarkable story of togetherness: a modern family shifting and pivoting to keep each person afloat. Early on, Svante chose to be the “housewife,” giving up a promising television career to stay home with the kids. When Greta sets out on her climate crusade, he manages, with quiet grace, the balance of support and distance that is a challenge for all parents. It is he who takes Greta to the hardware store to buy plywood and paint for her School Strike sign. The protest is her idea, and he understands that it’ll only work if she does it alone. On that first day, he cycles behind her, carrying the sign, then locks up the bikes and watches as she walks away to start her vigil.

One by one, other kids join her, and soon two activists from Greenpeace turn up. They bring a meal and offer it to Greta, thinking she might be hungry. At this point, Greta is still managing only small amounts of her few chosen foods; to Svante’s amazement, she takes the vegan Vietnamese noodles, sniffs them, then gingerly eats her way through the whole carton. As the strike progresses, she overcomes her mutism and her fear of children, too. After years of rough handling by her schoolmates, when a whole elementary class arrives, she has to step behind a pillar and gather her nerves before interacting with them.

When Caroline and I saw Greta that day in September, one of the things that struck me was how the teen activists who shared her stage seem to revere and love her. She’s come a long, long way. As her fame grows, there’ve been death threats on social media, complaints to child services, even shit put through the mail slot in the family’s door. But her voice just gets stronger.

Last week, at bedtime, Caroline told me that her friends don’t say “when I’m old,” they say “if I grow old.” She watched hours of YouTube footage of the Australian wildfires that raged in December, and cried over the dead kangaroos. She’s an animal lover and a vegetarian: It is very hard to know how to talk to her about these things.

Thirty years ago, the adults of the world could have fixed climate change with relative ease. Instead, as Greta says, we heard the fire alarm and went back to bed. It would be nice to tell Caroline that her generation will find a solution, that my mental image of this small, brave girl gives me hope. But that, also, would be a cop-out. One thing I can say: Grown-ups should read this book.