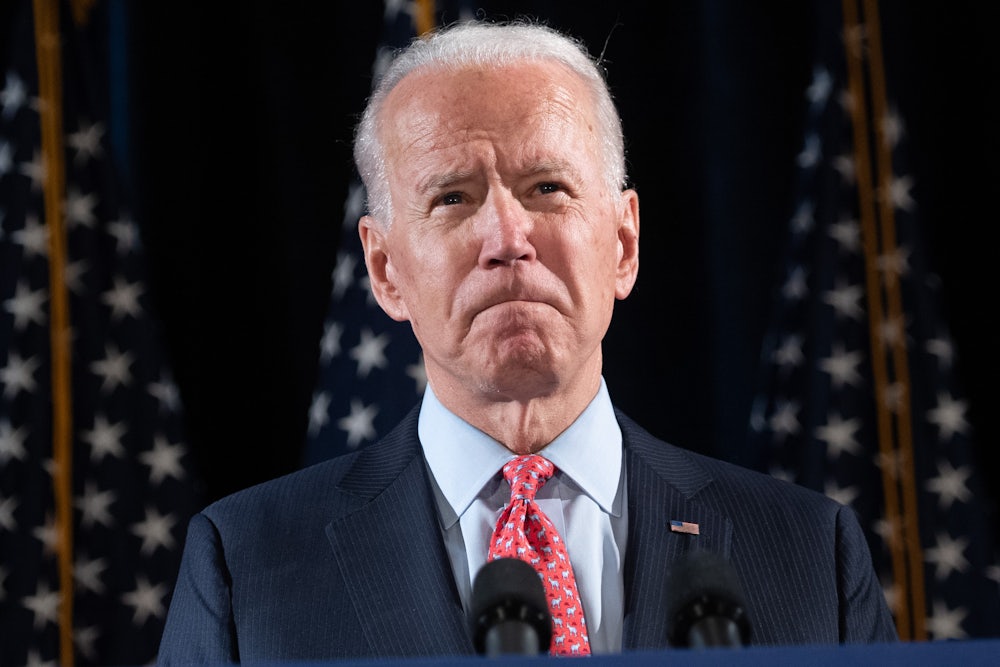

In a speech immediately heralded as “presidential,” Joe Biden addressed the coronavirus pandemic and laid out his proposal for limiting the “human and economic” toll of the illness. His plan includes many measures proposed by House Democrats, including emergency paid sick leave and providing free testing and treatment for the disease.

Biden certainly seemed more put-together than he has in recent weeks, and outlined a response that would be markedly better than the essentially absent response of the Trump administration. But this crisis offers an opportunity to make much bigger structural criticisms of the status quo, to illuminate to Americans exactly the kind of rot that has led us here and provide a vision for a better future after the virus. These are the kinds of criticisms that Biden has not yet put forward during his campaign. The coming days will be a test of whether it’s something he even wants to attempt.

It would seem as if it took the coronavirus crisis to spur Biden to take up the sort of policy planning that his fellow Democratic competitors have long made a feature of their campaigns. On paid sick leave, for example, Biden has proposed confronting the public health crisis with both emergency and permanent paid sick leave measures. But until today, Biden had made no mention of paid sick leave on his website; the only references to leave were a proposal to ensure “Americans have paid time off to take care of a newborn, elderly parent, or sick loved-one” on the “Women for Biden” page, and a promise to provide “paid domestic violence, sexual assault, and stalking safe leave.” There is no mention at all of vacation leave, something Bernie Sanders proposed in 2015 in his first run for president.

Paid sick leave is not something that should only occur to you once a pandemic threatens millions of lives and livelihoods. It deserved serious and empathetic attention from our presidential candidates long before news of the coronavirus first began to stir. Democratic candidates for president should understand and capably address the outrageous fact that America does not protect its wage workers—from waitresses and baristas to gardeners and nail technicians—from their bosses. If you are a wage worker who catches flu or pneumonia, can you afford to miss a shift unpaid? Can you afford to risk being fired or replaced for missing too many shifts? Workers with chronic illnesses like migraines live with the constant fear and stress of losing their jobs (and, often, their insurance). Did Joe Biden think about these people before this week?

The health care plan that Biden has proposed would have been inadequate to serve Americans had it been in place before the virus hit. The biggest problem with his plan, which has inexplicably not been a major issue in this campaign (to the discredit of the Sanders campaign), is that his plan, as described on his own website, would leave 3 percent of Americans without health insurance. That is roughly 10 million Americans who immediately fall through the cracks; only slightly fewer Americans than currently get their insurance on the Affordable Care Act exchanges, the approximate equivalent of the population of Michigan. It is not clear that Biden himself even knows or understands that his plan makes no accommodation for this population. He has never explained why his plan would leave 3 percent uninsured. Perhaps he believes this accounts for some intransigent group of people who would simply refuse affordable insurance on the basis of ideology, like libertarians who don’t believe in driver’s licenses. But there is no good reason to believe that this isn’t simply a planned, permanent feature of his health care plan: several million Americans for whom health insurance will remain an unaffordable luxury.

Beyond this minor detail, his plan works to retain a system where millions of Americans get their insurance from thousands of different plans, and where hospitals can charge inflated and arbitrary rates for tests and procedures.

Just went to Seattle’s UW Medical Center to ask how much patients are being charged for a coronavirus test.

— Michael Hobbes (@RottenInDenmark) March 11, 2020

$100-$500 if they have insurance.

$1,600 if they don’t.

This inefficiency is dangerous in a pandemic, as are the gaps and errors that a system like this inevitably creates. It’s also woefully weak on the question of affordability, arguably the main thing that prevents Americans from getting care today. Biden’s plan says it would “allow” Americans who purchase their plans on the marketplace to “afford” plans with lower deductibles by increasing subsidies, pegging the level of subsidies to the cost of a gold plan rather than a silver plan. His plan would reduce the income limit for subsidies (that is, the percentage of a person’s income that a marketplace plan can charge them for premiums alone) from 9.86 percent to 8.5 percent—hardly the sort of vast increase in affordability that is needed. And this is just for marketplace plans; it does nothing for the 150 million Americans who currently get their insurance through their employer.

Biden has come a cropper on the question of whether his proposal would allow an “automatic buy-in” onto the public plan before; in a debate last year, he claimed that “every single person who is diagnosed with cancer or any other disease can automatically become part of this plan.” He has never explained how this would work. These questions are absolutely vital to answer at the time of pandemic, but again this merely exposes a flaw that already exists: If you lose your job, or miss a payment on insurance, or if any other number of life’s landmines gets you, you might not be able to get treated for an illness. When that illness is a pandemic, it becomes a public health crisis. But when the illness is personal, it is still a tragedy and an outrage. Actively working to preserve the bizarre system of employer-sponsored insurance is foolish at the best of times, but it is pure madness during a pandemic and possible recession. Layoffs are already happening, and millions may lose their insurance, which has consequences far apart from the virus. People may lose their homes—something that other Democrats have proposed solutions to as part of their response.

The coronavirus pandemic is a threat the likes of which we have not faced in years, but in many cases, it has merely laid bare the perpetual rolling emergency that is American society today. A society that cannot guarantee its citizens health care is a society in crisis. A society where the poor are at greater risk of illness and early death is a society in crisis. A society with poor people at all is a society in crisis. As we try to address this pandemic, we will encounter wound after wound, raw and bloody, in our collective lives. Only systemic change can heal them—not a return to a more quietly violent past.