The crumbling of Elizabeth Warren’s presidential campaign just after Super Tuesday also spelled the end, many have mourned, of the most diverse primary field in history. The 2020 Democratic race started last year with a slate that rivaled a Coca-Cola ad— the first black woman to serve as attorney general of California, the first black (and likely first vegan) senator from New Jersey, a Latino former Obama Cabinet member, an openly gay Midwestern mayor, an Asian American entrepreneur turned philanthropist—but has since dwindled to “two straight white septuagenarian men fighting over the soul of the party,” as The New York Times wrote on Wednesday.

It was inevitable that the primary field would eventually narrow, but for many watching the election play out, the fact that both of the Democratic primary candidates left standing are white men currently eligible for Social Security benefits signaled a major problem. As Vox’s Li Zhou wrote in the wake of Cory Booker’s January departure, “It’s striking that in a party in which 40 percent of voters are people of color, the debate stage won’t be nearly as representative.” Or as CNN’s Swanee Hunt wrote after Warren ended her campaign, “Given that 100 long years ago American women gained the right to vote, it’s hard for many of us to fathom the fact we have yet to take our seat behind the desk in the Oval Office.”

So what has kept Democratic voters from nominating a woman or nonwhite candidate? Despite data showing that women and people of color are, once on the ballot, as likely as their white male counterparts to win elections, a popular theory remains that even when voters profess progressive commitments, a majority are—either consciously or unconsciously—too racist, sexist, or homophobic to cast a ballot for anyone other than a straight, cis white man. That was a common argument after Hillary Clinton’s devastating 2016 loss to the garishly unqualified candidate who now occupies the Oval Office. And for some, the biases and bigotry of the electorate also explain the homogenization of the 2020 Democratic field. “The candidates who dropped out and the order in which they gave up their campaigns reflect the exact hierarchy of oppression this country has executed since before it was founded,” journalist David Dennis Jr., the son of Freedom Rider Dave Dennis, wrote in The Washington Post last month.

There are plenty of reasons for cynicism when it comes to the political process: Our country’s history—and present practice—of disenfranchising voters through racist voter identification laws and gerrymandering; the 2010 Citizens United ruling that turned elections into shopping sprees for the rich; and decades of wildly unaccountable politics that have left many voters feeling, rightly, that the system does not actually serve them.

But another explanation for why the 2020 primary now looks like it does is that diversifying the political establishment—that is, the very governing class that a majority of people say they don’t trust, for many of the same reasons just mentioned—is a project that’s of greater interest to the media and the Democratic Party elite than it is to most Americans. In an April 2019 Monmouth poll, 87 percent of Democratic voters said that the race of the eventual nominee wasn’t important to them; 77 percent said that the gender of the nominee didn’t matter. In other words, for the majority of voters, the identities of the candidates, no matter how historic, came secondary to other concerns.

Take, for instance, the division between those who championed Kamala Harris’s bid and those who didn’t. Harris won early endorsements from a long list of Democratic insiders and celebrities, who applauded the unprecedented nature of her candidacy. But even before primary voting officially began, Harris failed to generate significant support among African American voters, lagging behind both Biden and Sanders in terms of polling and individual donations.

Black voters, who are often treated as a monolith, had other priorities in choosing their candidate, as Times reporter Astead Herndon wrote last year. “Within South Carolina, within the African American community, we don’t want to take a chance on someone that doesn’t have a chance of beating Trump,” Dan Webb, a 58-year-old South Carolina resident, told him. For that reason, Webb went on to explain, he supported Biden. Another voter, Atlanta resident Amber Lowe, framed her support for Warren as a matter of priorities. “I want black women in office, I do, and I love Kamala Harris and think she’s amazing, but I’m just more policy-focused,” she told the Times. The failure of representation alone to translate into strong support was true of Cory Booker, too, who also underperformed with black voters, and of Julián Castro, who never gained real traction among Latinx voters.

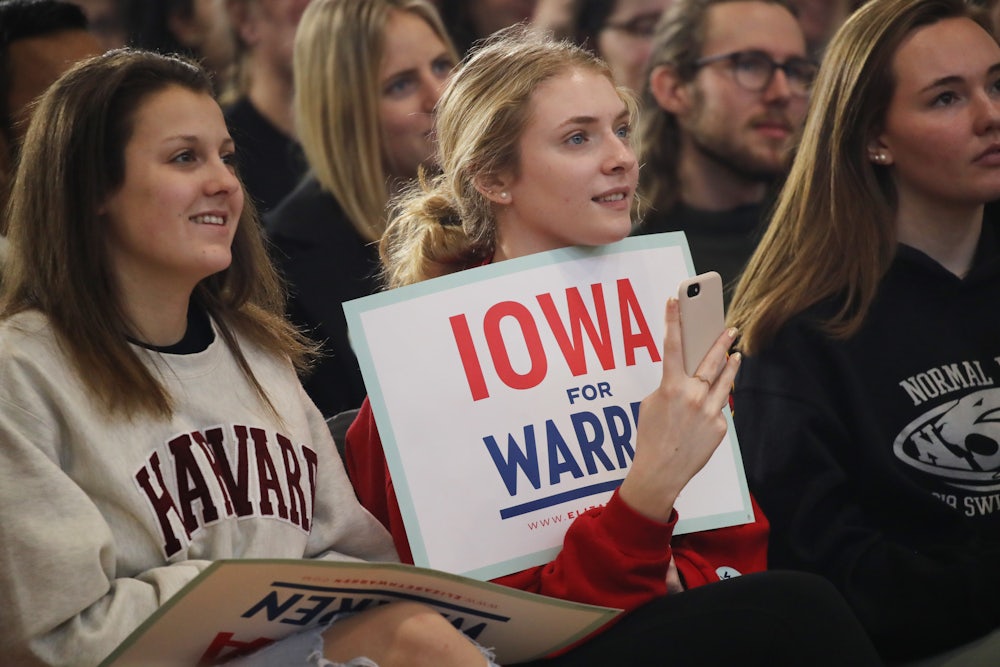

Other, more recent polls from the ongoing Democratic race have also suggested that politicians’ identities may be of less interest to the voters who share those identities than commentators sometimes assume. For example, though Pete Buttigieg secured a narrow delegate victory in Iowa—along with endorsements from celebrities like George Takei and the backing of groups like the LGBTQ Victory Fund—a poll in Iowa found that Bernie Sanders had nearly twice the support of Buttigieg among LGBTQ respondents in that state. Similarly, according to exit polls from Super Tuesday, only one in 10 women voters cast a vote for Warren in her own home state of Massachusetts (compared to three in 10 for Sanders and around a third for Biden, who eventually won the state). Judging by voting patterns so far, the symbolic triumph of “seeing oneself” in the presidency didn’t much compel the average voter this time around.

Still, as the wave of emotional responses to Warren’s departure from the race indicates, representation does matter to many voters. It just might also be the case that this particular kind of representation—or this kind of representation alone—perhaps matters more when you’re part (or within arm’s reach) of the comfortable political class yourself. After Buttigieg ended his campaign last week, his husband, Chasten, delivered an emotional speech calling the campaign an inspiration to LGBTQ youth. “Pete got me to believe in myself again,” he said. “I told Pete to run because I knew there were other kids sitting out there in this country who needed to believe in themselves too.”

That feeling of inspiration isn’t strictly limited to the well off, but it might be more fleeting for those who also have to worry about things like wages and the cost of health care. Any conversation about representation or identity emptied of that reality will always fall short. As Harron Walker wrote after progressive Democrat Christine Hallquist lost her 2018 race to unseat Vermont’s Republican governor, the “first trans governor” framing that followed her campaign never fully captured the scope of what she was trying to build with her candidacy. “Hallquist herself bristled against the ‘first trans’ framing, mostly because it obscured the actual stakes of what she ran on: a living wage and economic justice in a state where more than 1 in 10 people still live in poverty, collective bargaining and an energized labor movement, criminal justice reform that addresses the system’s staggering racial disparities in a nearly all-white state, a focus on climate change and renewable energy,” Walker wrote.

There are all kinds of firsts, then. “My seven-year-old son and I watched the debates together. I was proud he could see an Asian on stage in Andrew Yang,” Kenzo Shibata, a Chicago-based public schoolteacher, told The New Republic. But, he continued, “I’m just as proud to tell my son that I did not vote for Yang because I don’t agree with his ideas.” Shibata viewed Yang’s signature universal basic income proposal as a nonstarter; as the president of the Illinois chapter of the Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance, he endorsed Bernie Sanders. This, perhaps, is another way of seeing yourself in a candidate, though not the one many mainstream media narratives tend to emphasize when talking to or about voters of color.

For those attempting to balance a genuine desire for a diverse governing body with policies that would help working people, the rise of a new crop of politicians at both the national and local levels—including unapologetically progressive members of Congress such as Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib—suggests that, increasingly, voters might not have to choose. But as the anxiety over the relative homogeneity of the presidential race continues, it’s worth remembering that while many voters want to see themselves in their candidate, they also want their candidate to be able to see him or herself in their voters. That would mean a candidate who knows they’re running for office to actually serve the needs of their constituency. You might even call that representation.