In the midst of a presidential cycle with Donald Trump and democracy itself on the ballot, the 2012 election between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney seems, in hindsight, as benign as a P.G. Wodehouse novel.

Sure, there were misadventures—Obama’s flailing first debate, Romney’s claim that 47 percent of voters are on the government dole. But these episodes were about as serious as Jeeves rescuing Bertie Wooster from an ill-considered romantic attachment. The Obama-versus-Romney contest featured two good men (see Romney’s impeachment vote) who strongly disagreed on taxes and social issues—pretty much how things should be in a robust democracy.

But the 2012 race also badly wounded political journalism—and eight years later the scars are still visible in the misguided coverage of the 2020 Democratic primaries. From the overhyping of candidates like Kamala Harris to the breathless worship of misleading polls, the media has been consistently and unapologetically wrong in chronicling the 2020 Democratic race.

Why did things go so awry back in 2012? It was no one’s fault, exactly. It was just that the 2012 election was too easy and too predictable—creating a false sense of confidence that handicapping politics required little more than following the polling averages and watching cable shows such as Morning Joe.

As political scientists John Sides and Lynn Vavreck point out in The Gamble, their academic study of that year’s election, “The race was not hard to call. Virtually everyone aggregating the public polls believed that Obama was going to win and with a high probability.”

This was the campaign when Nate Silver became lionized as the greatest political genius since Boss Tweed rigged his first precinct. Silver, originally a baseball forecaster, went from a blogger who predicted 49 out of 50 states correctly in 2008 to a New York Times celebrity who correctly called every electoral vote in 2012 for the paper of record. After the 2012 election, Times executive editor Jill Abramson marveled about Silver at a conference, “He got huge, huge readership. Half the people coming [to NYTimes.com] searched for Nate. They weren’t coming for the rest of the Times; they came for him.”

Another trend in journalism, accelerating in 2012 and afterward, contributed to the slavish devotion to polls. The brutal economics that devastated newspapers and all but destroyed newsmagazines produced a younger (and, of course, cheaper) campaign press corps. As CNN’s Pete Hamby, now covering the 2020 campaign for Vanity Fair, wrote in a 2013 paper for the Shorenstein Center at Harvard, “Since the 2004 campaign, with budgetary and deadline pressures weighing heavily on editors, news outlets have increasingly opted to send younger and more digitally savvy reporters on the road with campaigns.”

Let me stress that some of these millennial journalists—especially those writing for newspapers—are as good, if not better, than the old guard who first hit the road in the 1980s with their bulky Radio Shack TRS-80 computers (universally known as “Trash 80s”) and their acoustic couplers. But the rapid generational turnover on the campaign beat has collectively created a press corps less confident in its judgments and even more nervous about straying from the pack and the Twitter mob.

In The Boys on the Bus, Timothy Crouse’s enduring portrait of the chain-smoking reporters covering the 1972 campaign, he correctly points out, “Everybody denounces pack journalism, including the men who form the pack. Any self-respecting journalist would sooner endorse incest than come out in favor of pack journalism. It is the classic villain of every campaign year.”

What creates pack journalism—then and now—is the simple human reality that no one wants to be wrong. It’s embarrassing, whether you are a reporter, a columnist, an editor, or a TV talking head. And presidential primary races, beginning in the odd-numbered year and then continuing state-by-state, give everyone ample opportunities to conspicuously botch political coverage. As a result, it’s far safer to operate within the prevailing consensus—to conform to the dictates of a pack that derives its conclusions from polls and fundraising data—than to say ruefully after a wrong call, “Well, I had this hunch....”

In theory, the 2016 campaign should have served as electroshock treatment—a violent dose of uncut reality that should have cured the press pack of its certainties about anything. Let us repress all memories of election night 2016, especially the New York Times needle under the custody of the Upshot column. Nate Silver had left the newspaper, together with his FiveThirtyEight website, but it is convenient to describe the many other polling analysts and political handicappers now at the Times and elsewhere as card-carrying members of the School of Silver.

Even putting Trump aside, the media made several miscalls during the 2016 primaries that should have permanently halted all premature rushes to judgment. The obvious one was kneeling in awe over Jeb Bush’s $118 million super PAC. When Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker entered the GOP scrum during the early summer of 2015, the gushing was deafening, and nearly universal. For example, MSNBC’s website stated flatly that Walker was in “the top tier” and insisted that he “has a legitimate path to the nomination if he can exploit concerns on the right over rivals like Jeb Bush, who has ruffled feathers with his immigration and education positions, and Marco Rubio.” Two months later, Walker was out of the race with a surrender so sudden that Ted Cruz’s immediate response on Fox News was “Holy cow.”

The other major non-Trump-related miscue of 2016 was the dismissal of Bernie Sanders as a serious contender for the nomination when he declared his candidacy in April 2015. In another classic case study of pack journalism, the hat-in-the-ring pieces appearing in major political news outlets struck the same tone. Politico: “Sanders will be a long-shot—he has little campaign infrastructure, a limited fundraising base and trails [Hillary] Clinton by a wide margin in the polls.” The New York Times: “Mr. Sanders’s bid is considered a long-shot.”

By 2016, political reporters should have grasped the power of online fundraising, especially since Howard Dean had transformed the 2004 Democratic race with his pioneering small-donor juggernaut. But once again—with a lack of imagination that equated fundraising with pocketing checks in Park Avenue living rooms—the media failed to appreciate this new-fangled gizmo called the internet. Defiantly ignoring his supposedly limited fundraising base, Sanders ended up collecting a stunning $228 million in his vigorous primary challenge to Hillary Clinton.

The biggest lesson for the media from the 2016 campaign also had to do with money—or, more precisely, profits. Trump proved that there was no longer the obligation to cover politics out of a sense of civic duty, as CBS and its broadcast rivals did in the era of Walter Cronkite. Now politics had become a profit center for the television networks in the same way that sports coverage bulks up revenue—with the added advantage that no one had to pay the equivalent of licensing fees to the NFL.

Maybe the 2020 media crack-up was inevitable. It stemmed from a potent combination—a relatively inexperienced press corps genuflecting before every new poll while serving corporate masters who saw dollar signs the moment anyone uttered the magic words “Iowa” and “New Hampshire.”

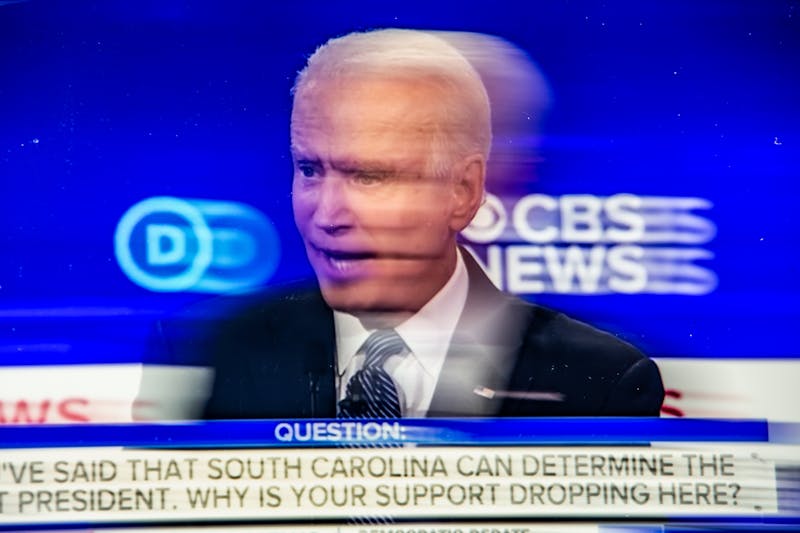

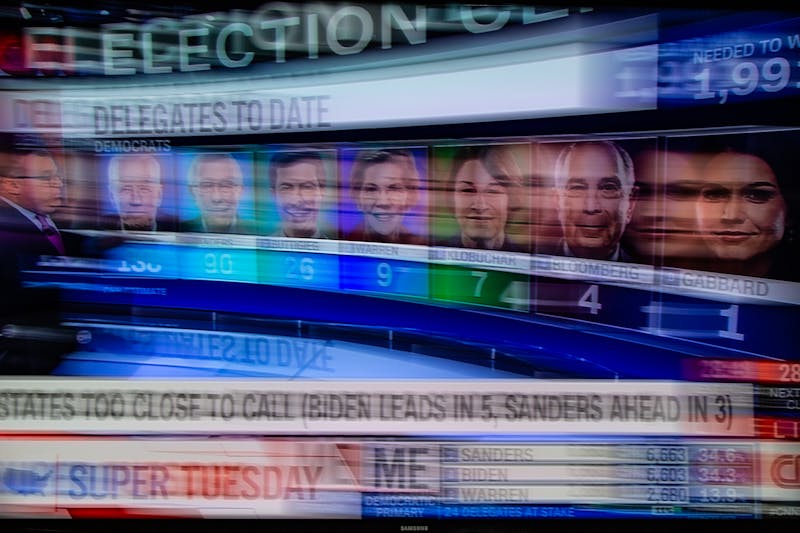

But as I write this in the initial phase of primary voting, with the identity of the Democratic nominee still unknowable, I am saddened by the state of the profession (or, better yet, the calling) to which I have devoted four decades of my life. I have certainly made my share of 2020 mistakes, a few of which I will detail below. But I hope that throughout the campaign I have also displayed a hard-won humility about my limited abilities as a seer and a soothsayer. During the first three weeks of February alone, we have had five separate and semi-contradictory story lines: Joe Biden will limp to inevitable victory; Sanders is the likely delegate leader; it’s a Bernie-versus-Mike Bloomberg race; welcome to a contested convention in Milwaukee; and after the Nevada caucuses, Sanders is unbeatable.

Each time that the narrative shifted overnight, most political reporters reacted as if Oceania had always been at war with Eastasia. Rather than publicly acknowledging how volatile the Democratic race had always been, the media replaced old certainties with new ones. You could almost feel empathy for the pundits who got caught clinging to prior forecasts as the party line shifted. Less than 48 hours before the Las Vegas debate in which Bloomberg had the worst notices since Our American Cousin played in Washington in 1865, CNN’s nightly political newsletter was headlined, “Why Bloomberg May Turn Unstoppable Soon.” And FiveThirtyEight weighed in with a polling-centric piece proclaiming, “Bloomberg’s Super Tuesday Gamble May Be Paying Off.”

After Bloomberg’s brutal debate audition, Silver immediately offered his own corrective take on FiveThirtyEight under the headline, “The Debate Exposed Bloomberg’s Downside — But It Was There All Along.” Silver, who to his credit has consistently been more cautious in 2020 than many of his counterparts, wrote, “The hype about Bloomberg—a candidate who had yet to compete in any states, to participate in any debates, or to face sustained scrutiny from the media and other candidates—had probably gotten out of hand.”

The truth is that while the demand for political stories is nearly inexhaustible, the supply chain is often short of new information or insights. So the story of 2019, in particular, was a tale of hot takes and takedowns buttressed by evanescent evidence. Through it all, reporters and pundits alike blithely ignored the evidence that most Democratic voters (even in Iowa and New Hampshire) weren’t paying attention. Campaign coverage before the Iowa caucuses probably would have spread far fewer misconceptions if the political press corps had taken two-week breaks each time the news slowed down. But, of course, there was cable TV airtime to fill, relentless online deadlines to meet, and front-page real estate to grab.

As an illustration, take a look at two soporific weeks in July 2019 when little of lasting consequence happened in America, aside from the arrest of Jeffrey Epstein. It was a time of mostly one-column headlines leading the print version of The New York Times. I deliberately chose the period from July 5 to July 19 because it was comfortably after the June 27 debate in which Kamala Harris had challenged Joe Biden over busing in the 1970s with the dramatic and rehearsed line, “And that little girl was me.” This was summertime and the living should have been easy. And indeed it was, almost everywhere—except on the political beat, where the Harris boomlet had forecasters all but speculating about the location of her presidential library.

On July 5, The Washington Post cushioned Harris’s blah second-quarter fundraising numbers (less than half the $24.8 million raised by Pete Buttigieg) by calling the California senator’s nearly $12 million haul “a substantial take but one that lags some of the other top-tier Democratic White House hopefuls.” The Post article alluded to Harris’s postdebate momentum by noting that the campaign had raised nearly $500,000 from an online store that was hawking “That Little Girl Was Me” t-shirts. Two days later, Harris and Elizabeth Warren shared the New York Times front page in a story about how “a new, highly uncertain phase” of the race was “propelling a pair of women toward the top of the Democratic pack at the expense of onetime front-runners, Mr. Biden and Senator Bernie Sanders.” Amy Klobuchar—who went on to receive more than twice as many votes as Warren in the New Hampshire primary—was mentioned at the tag end of a single sentence.

Rachel Maddow began her July 11 show—in which she would later interview Harris—with a bravura performance. She initially disdained polls and poll-driven political narratives—and then proceeded to gush over a new NBC News/Wall Street Journal national survey. “I know you know how I feel about spending too much time on polls and all that horse race stuff,” Maddow soberly began—and before you knew it, the same self-declared poll skeptic was offering head-spinning detail about the new poll, co-sponsored by her parent network, showing that Harris was tied with Bernie Sanders for third place, with 13 percent, well behind Biden and Warren.

Known for her intellectual mien on camera, Maddow sniffed at the actual top-line numbers, while noting that only 12 percent of Democrats were certain of their choices. What animated Maddow—probably the most influential cable TV host for Democratic voters—were the microscopic differences that awarded Harris a tick more second-choice support than any of her rivals. (The actual numbers: Harris 14 percent, Warren 13 percent, and Sanders 12 percent.) To Maddow, who had apparently forgotten concepts like margin of error, these virtually identical figures were almost enough to propel the first-term California senator to victory at the Milwaukee convention: “Kamala Harris, more than anybody else in the field, appears to be the candidate in the top tier right now who has the most room to run. Who has the most... potential support out there from Democratic voters who haven’t yet committed to who they like.”

That same day, over at CNN, Chris Cillizza and Harry Enten breathlessly offered their monthly “Power Rankings” of the Democratic field. So what if this was still nearly seven months to the Iowa caucuses? Nothing could be more vital for CNN viewers and readers than to ponder a ranking of all the Democratic contenders based on little more than white puffs of smoke. And sure enough, there in second place (just behind Biden) was Harris. As Cillizza and Enten explained, “What a difference a debate makes. The junior senator from California had frequently topped our power rankings for much of 2018 but had fallen behind before the first debate. But after her debate showdown with Biden, Harris has seen her polling boom.”

It’s admittedly easy to mock the gossamer certainties of cable TV. But the pundit parade’s avatar of unabashed primary-season error was not a television talking head, but a veteran print journalist. On July 19, Gerard Baker, who had been editor in chief of The Wall Street Journal until 2018, offered his definitive judgment of Harris and the Democratic field in his weekly column for the newspaper: “There’s not much doubt that the California senator has suddenly become the sensation of the primary season so far. In the space of a month she has traveled from the crowded middle of the distant second tier of candidates to, arguably perhaps, the front of the front. It’s difficult to recall such a sudden shift of fortunes in a primary contest absent an actual primary or caucus vote.”

These days, it’s hard to recall anything like Harris’s subsequent sudden shift of fortunes downward—without either a scandal or a single vote being cast. (Scott Walker never rose as high on the pundit hit parade.) In early December—with dwindling finances, a bickering staff, and widespread disdain for her themeless campaign—Harris joined Bill de Blasio and Kirsten Gillibrand in the dustbin of the 2020 Democrats. In retrospect, the apogee of the Harris campaign may have come when Maddow crowed during her mid-July monologue, “She’s obviously turning heads. She made a huge impression with her performance in the first debate—a commanding performance.”

I never jumped on a float in the Kamala cavalcade. But before I bask in my moral superiority, I had better confess to my own bum call last spring. In an early June dispatch from Iowa for The New Republic’s website, I threw a lifeline to Beto O’Rourke just when it correctly appeared to many others that he was going down for the third time. Despite O’Rourke’s 2 percent support in the latest Iowa Poll, I bravely (no, make that “foolishly”) wrote, “In covering presidential politics, there are moments when you have to choose between the polls and what you see with your own eyes. After following O’Rourke for most of two days, I am going with my instincts.” In early November, fearful of not qualifying for the next debate, O’Rourke (the one-hit wonder of Democratic politics) went with his own instincts and quit the race.

My Beto boomerang was mostly based on my contrarian skepticism about early polls—especially those that obscured the real preprimary state of indecision that had most Democrats struggling to identify a standard-bearer in the multicandidate field. It was a rough rule of thumb that the more any pundit was tethered to a TV green room, the more he or she treated the latest polls as holy writ. Talking to voters in Iowa and New Hampshire brought home the obvious message that beating Trump mattered far more than ideological purity. But on TV, there was more chatter about “lanes” (progressive, centrist, or whatnot) than could be heard on any walking tour of the British countryside. Democrats in Iowa and New Hampshire have historically been late deciders, according to entrance and exit polls. In 2008, the last serious multicandidate Democratic race, 27 percent of Iowa caucus-goers decided in the last week, and 51 percent made their choices in the final month. In New Hampshire that year—where Hillary Clinton rebounded from a nearly 10-point polling deficit at the last minute to nip Barack Obama—21 percent of the Democratic primary voters picked their candidate in the final three days. At the time, Michael Traugott, a polling expert at the University of Michigan, said, “The most jarring element of the presidential primary polling was that the polls picked the wrong winner in New Hampshire.”

Too many political reporters, and quite a few candidates, felt frustrated by the stubborn refusal of voters to make their decisions for the convenience of the pollsters rather than at the polls. In hindsight, all 2020 polls should have been introduced with a prominent disclaimer announcing that these premature surveys possess the accuracy of medieval cannon fire. Nevertheless, TV and print reporters peddled the illusion that the latest polls offered an exclusive window into the future.

How bad was the pre-Iowa and pre-New Hampshire polling? Think of the Edsel, the 2000 butterfly ballot in Florida, and the movie version of Cats.

Elizabeth Warren led or tied in eight Iowa polls from mid-September to early November. She ended up third in the caucuses. Joe Biden led or tied in four separate Iowa polls in January 2020. On February 3, he limped home an embarrassing fourth.

Polling in New Hampshire—where roughly half the 2020 Democratic voters said they made up their minds in the final few days—was equally erratic. In four successive polls at the end of January, Biden received at least 20 percent support. And in no poll in the year before the February 11 primary did the former vice president tumble into single digits. (He ended up a humiliating fifth, with just 8 percent of the vote.) Klobuchar scored at 6 percent or lower in eight separate New Hampshire polls in February. Powered by a stirring debate performance just before the primary, Klobuchar instead finished third in New Hampshire, with 20 percent of the vote.

This is the point in many media jeremiads when readers are braced for a high-minded paean to issue coverage and a tearful lament about why journalists fritter away their time with horse-race coverage. But that is not my crusade. No one, after any campaign trip during the 2020 campaign season, asked me over dinner, “Could you explain in detail Pete Buttigieg’s view of nuclear power?” or stopped me on the street to inquire how Elizabeth Warren planned to handle the valuation of Old Masters under her wealth tax.

In contrast, friends constantly barraged me with questions about who is going to win the Democratic nomination. Of course, reporters should write about all the holes in the policy proposals of the candidates. Bernie Sanders, for example, should be challenged more on his airy answers to questions about how he would pass Medicare for All with a Senate where most Democrats (let alone Mitch McConnell and Company) oppose the elimination of private insurance. Responses like “build a mass movement” simply won’t cut it—nor is ending the filibuster (as Warren proposes while Sanders disagrees) the solution to all Democratic legislative dilemmas.

Horse-race coverage remains inescapable because of the formidable demand for it among readers and TV viewers. But the goal should be to do it smartly—a trick that totally eluded campaign reporters in the year-long run-up to Iowa and New Hampshire. Bad punditry and predictions are not victimless crimes, no matter how secure columnists and cable TV hosts are in their jobs. Fundraising dries up for candidates if the media constantly tells would-be donors that they cannot win. Just ask Cory Booker, the last serious African American candidate in the race, who yielded to the inevitable in mid-January after months of threatening to drop out if he couldn’t meet his fundraising targets.

Oddly enough, the press pack may have been more adept at handicapping presidential nomination fights back in the old days when reliable polls were rare and shoe-leather reporting was prized. In The Boys on the Bus, Crouse pauses to praise the rare woman on the 1972 campaign trail, Cassie Mackin of NBC News. Mackin, according to Crouse, “knew the names and salient features of about three hundred county chairmen.”

What could be more retro than seeking out the views of county chairmen, those potbellied, cigar-smoking relics of the political past?

Except for one pesky detail: Even in the smokeless America of today, county chairmen may do a better job than most polls in predicting political winners. For a yet-to-be-published academic study of the 2020 Iowa caucuses, University of Delaware political scientist David Redlawsk surveyed Iowa Democratic county chairmen and other local party officials about which candidates were apt to do well in their counties. Based on responses from almost half of Iowa’s 99 counties, Redlawsk discovered that these party stalwarts possess a keen sense of the political mood of their home turf. In 56 percent of the cases, these party officials correctly predicted which candidates would finish in the top two in their counties.

If there was a single moment that captured what is wrong with contemporary political coverage, it was a mid-January appearance by Joe Scarborough and Mika Brzezinski on The Late Show With Stephen Colbert. Both Scarborough and Brzezinski radiated the self-confident hauteur of leading art historians confronted with a well-meaning amateur who knows what he likes.

Colbert began by cheerfully reminding the couple that during their last appearance on his show, they had unequivocally declared that the front-runners for the nomination were Kamala Harris and Joe Biden. After Colbert suggested that perhaps even the Biden portion of that prediction needed updating, Brzezinski broke in to ask in a voice dripping with exasperation, “Show me the data where he’s losing and he’s not even the front-runner anymore? That’s ridiculous.” Moments later, Scarborough added, “The amazing thing about Joe Biden is that he’s like Trump in that he’s Teflon. It doesn’t matter how he does in debates.... He just keeps on keeping on.” That comment seemed more a lucky guess than Scarborough somehow anticipating Biden’s death-defying comeback in the Democratic race.

Forgive my temerity, but I’ll take an Iowa county chairman any time.