“Nobody likes him!” Hillary Clinton said of Bernie Sanders in remarks taped last year for a documentary. She didn’t mean it literally, of course. Lots of people clearly like Sanders, sometimes with a fervor that irks Clinton’s fellow Democrats. She meant nobody useful: “Nobody wants to work with him! He got nothing done.” Clinton, like most people who consider themselves canny political realists, seems to divide politicians into two groups: those who make big promises, and those who Get Things Done.

But what do the politicians who Get Things Done actually get done? In 2018, The New York Times’ editorial board said Governor Andrew Cuomo of New York “gets big things done when he’s determined.” While blunt about his flaws—he was a little corrupt, sure—the board made the case for reelecting Cuomo clearly: “When focused, [he] can be a nearly unstoppable force for progress.” That election not only won Cuomo a third term but also gave him a large—and even more liberal—Democratic majority in both the state Senate and Assembly. Getting things done would no longer require a Democratic governor’s “focus,” merely his pen. 2019 would become the “most productive legislative session in modern history,” in Cuomo’s own words. By June, the legislature had passed 935 bills.

As of December 16, the Times reported, 168 remained unsigned. Then came the vetoes. The legislature passed a bill aimed at helping workers recover stolen wages. Cuomo vetoed it. It passed a bill legalizing the electric bicycles commonly driven by New York City’s food delivery workers, who are currently the targets of an absurd police crackdown. Cuomo vetoed it. It passed a bill aimed at increasing wages for some apartment building workers. Cuomo vetoed it.

By January, he had vetoed 169 bills passed during that historically productive session. The governor promised to reintroduce some of these measures, in modified forms, in 2020. But the message was clear: The main thing Andrew Cuomo gets done is deciding what gets done and what doesn’t.

When politicians and pundits implore voters not to put their faith in candidates with more expansive visions, they frequently say they do so for the sake of the voters themselves. As Clinton put it in the documentary (reviewed on page 66 of this issue), “I feel so bad that people got sucked into it.” Later, speaking to Ellen DeGeneres, she elaborated on her problem with Sanders’s political style. “[I]f you promise the moon and you can’t deliver the moon, then that’s going to be one more indicator of how, you know, we just can’t trust each other.” Left unsaid was that Clinton had made a promise of her own in 2016: that her pragmatic sensibilities made her a safer electoral bet than Sanders. The general electorate would, we were assured, select the candidate offering judicious incrementalism over radical change. The November election saw that promise not just undelivered but spectacularly exploded, as voters in a few key states went with the man in the race who made the most outlandish promises of them all.

Yet our pragmatic moderates continue to claim that they alone know how to win elections. Rahm Emanuel appears hourly in print or on television to insist that Democrats stick to the playbook he used to win a House majority in 2006 (when George W. Bush had the lowest approval ratings of his presidency to date). What a candidate ought to do, according to an advisory Emanuel published online last summer, is imagine sitting at the kitchen table of an economically comfortable woman in “Grand Rapids or Green Bay” and promising her extremely incremental reforms. Trust him, it works. As he told the Times in February, “Every time we have won the White House, gained seats in the House and the Senate and the state capitals, we have run based on a model that has proved itself in presidential years, and off presidential years.” It is unclear whose playbook the Democratic Party was using during the presidency of Barack Obama, for whom Emanuel served as chief of staff, when it lost more than 800 state legislative seats. This is not to blame Emanuel for those losses; elections are partly cyclical, and partly random, and no one has an infallible strategy for winning them.

Emanuel knows as much, but he argues otherwise for the same reason Andrew Cuomo insists that he is indispensable (even though the primary justification for that claim was his talent in negotiating with Republicans who, as of 2020, have zero power in Albany): Both Cuomo and Emanuel want control of the agenda.

Invoking backlash to liberal overreach is key to maintaining that control. Asked on the radio in February whether Democratic members of the New York state Senate should be nervous about losing their majority in November, Cuomo couldn’t help himself. “They should be worried.”

“There are controversial laws that they passed, that have raised questions,” Cuomo said, as he raised the questions. Clearly annoyed that Democrats in the lower house had just thwarted his attempt to water down the bail reform law less than two months after it went into effect, he said, “Bail reform is one of them. Women’s right to choose is one of them—Catholic Church, Catholics, very upset. They think the woman’s right to choose law goes too far. The undocumented drivers’ licenses. The Trump people hate undocumented drivers’ licenses.” Having gotten things done, Cuomo seemed to be having second thoughts.

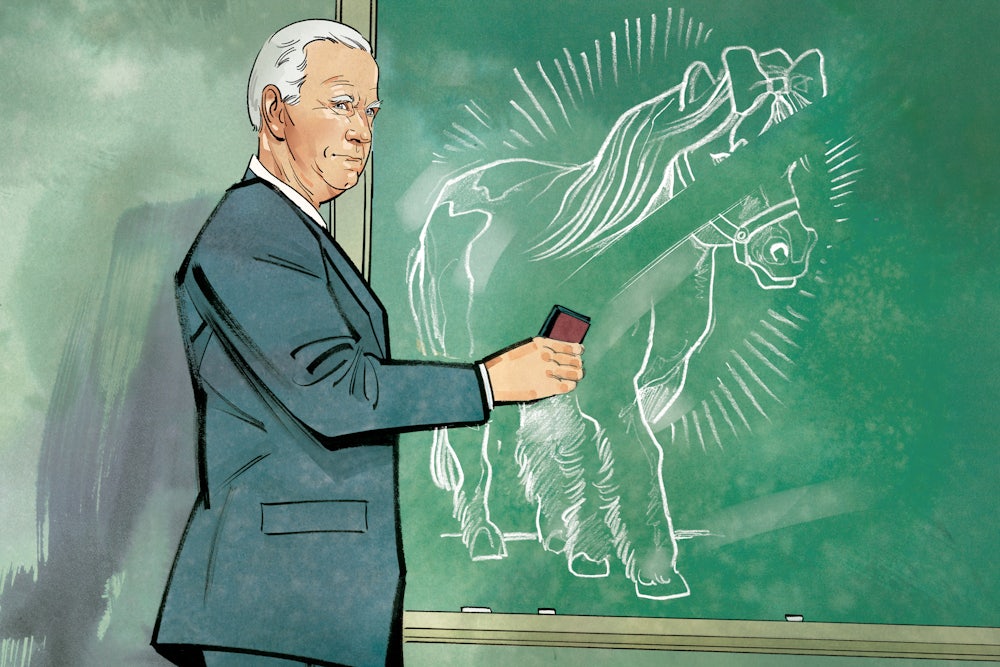

There is a reason why politicians use the language of realism rather than argue the merits of any specific issue; it’s why Clinton uses “the moon”—or, as she did in her 2017 memoir, “a pony”—to describe Sanders’s ambitious programs. What seems to irk these pragmatists is not strictly that promises like Medicare for All are, in their minds, impossible to enact, but that they are popular enough to force these pragmatists to come clean about why they oppose them.

It is perhaps unwise to make big promises and then fail to deliver on them completely, though we have no real way of testing that claim; a generation of Democrats has intentionally limited the scope of their promises. But moderates who speak out against proposing grand plans should be wary of a tendency in their own politics: They often claim to have delivered on their promises when, in reality, they didn’t. If you claim, for example, that you have given voters “tuition-free” public college, as Cuomo has been doing since 2017, people will eventually notice that SUNY and CUNY still charge tuition. If you constantly tout the rising graduation rate, as Rahm Emanuel did while mayor of Chicago, parents whose children were sent through storefront diploma mills to goose the graduation numbers will likely notice that the system isn’t working for their families.

Even the realists in this presidential race are making promises they can’t keep. In the days leading up to Super Tuesday, Joe Biden sounded familiar themes. “Bernie doesn’t have a very good track record of getting things done,” he told CNN. “Much of what he’s proposing is very much pie in the sky.” In a victorious speech on the night of Super Tuesday, the former vice president pledged, if elected, “to find, and I promise you, cures for cancer, Alzheimer’s, and diabetes.” Biden has a history of cribbing lines from other politicians, but I doubt he meant to echo the first president to make a similar promise—William Howard Taft, who said, according to a cancer research center he once visited, that we’d cure cancer in five years. This was 1910.

The final leader of the cult of pragmatism to enter the race was also perhaps the ultimate Getting Things Done politician. Former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg is often noted for his pure capability. Even his critics grant the premise, dubbing him, as Ross Douthat did, “ferociously competent.” One of his slogans was, “Mike will get it done.” He spent more than half a billion dollars chasing the Democratic nomination, only to win just one caucus—in American Samoa, with 175 votes.

His failure to achieve something that couldn’t be purchased calls into question his competence, and even his record. After 12 years with him in charge, New York City was transformed; the crime rate was down, housing costs were up. But even the richest man in town couldn’t have created the economic and social conditions responsible for those trends. He was stymied as much as any other mayor: on congestion pricing, on a football stadium, on securing the Olympics. On Bloomberg’s last day in office, trash still piled up in great heaps around the city on collection day, because no one could think of a better way to do it—or had the political will to change a failing system.