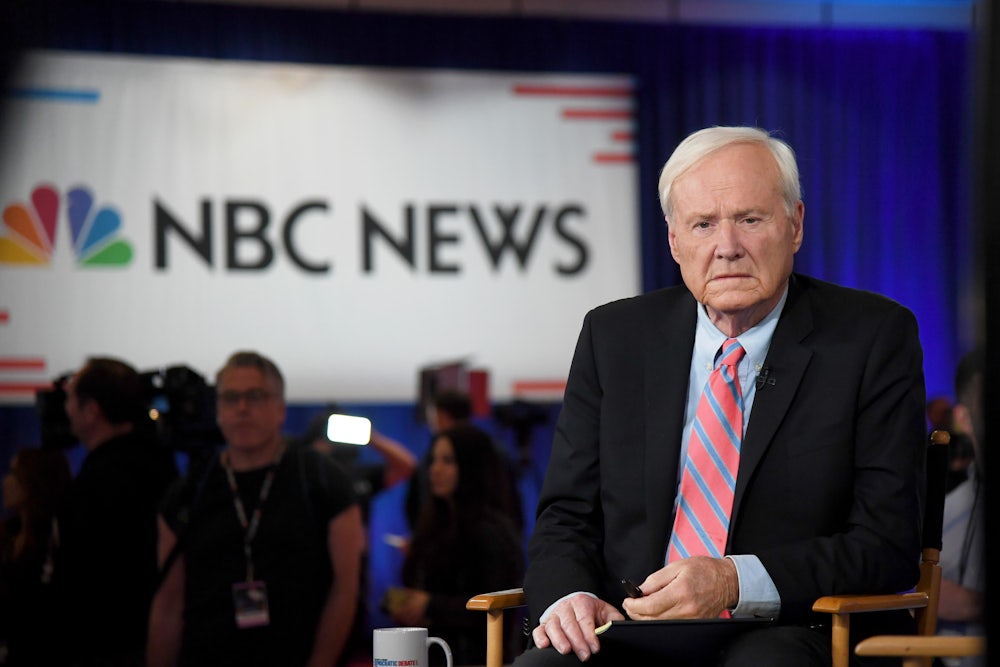

Chris Matthews’s abrupt resignation on Monday night shouldn’t have come as a surprise. He had spent the last two weeks doing the cable television equivalent of Sideshow Bob stepping on rakes—comparing Bernie Sanders’s campaign to Nazi Germany, asking Elizabeth Warren a series of sexist questions about workplace sexual harassment, being accused of harassment himself (again). Things had gotten so bad that Matthews, a staple on MSNBC for 23 years and four presidents, had been pulled from the network’s election coverage.

And yet his departure was shocking. That’s partly because surprises rarely happen in the television business—by nearly all accounts, no one expected him to walk away (even if everyone expected him to be pushed out eventually). But the main reason his retirement was so jarring is that Matthews is synonymous with cable television punditry. He was, in The New York Times’ Mark Leibovich’s words, “the carnival barker” at the center of “the echo chamber.” Matthews may be stepping down, but his legacy—the shallow, bombastic style of rapid-fire commentary that he helped pioneer—lives on.

Matthews’s alleged appeal was, as David Greenberg wrote in The New Republic in 2012, in being “the garrulous guy on the barstool, who tells funny stories but who is there primarily to entertain.” A former speechwriter for Jimmy Carter who also spent six years working for Speaker Tip O’Neill, Matthews loved nothing more than sepia-toned stories about the good old days. A creature of the Clinton era, he tried to make himself into a blue-collar sage for his liberal viewers, an Irish uncle who trumpeted hard hats and slammed eggheads. He was romantic about politics in the way that people get romantic about things after a long night at the bar. “I am not a cheerleader for politics per se,” Matthews told Leibovich in 2008. “I am a cheerleader for the possibilities of politics.”

But Matthews was absolutely a cheerleader for politics, in the sense that he saw the whole thing as a game. Issues themselves didn’t animate him, so much as conflict between teams—Democrats and Republicans, most of all. In 2007, Jon Stewart tore into Matthews’s book Life’s a Campaign, which instructed its readers to act more like politicians in their everyday lives. (The premise sounded only slightly less ridiculous then than it does now.) Calling it “a self-hurt book” and “a recipe for sadness,” Stewart added, “If you live by this book, your life will be strategy, and if your life is strategy, you will be unhappy.”

That particular interview touched on another unseemly aspect of Matthews’s career. One of the lessons in Matthews’s book is that it is good to listen to people. “Bill Clinton, when he was in college, would get women, girls, in bed by listening to them,” Matthews told Stewart. “He was a great listener. When friends of his couldn’t get the girls of their dream, he’d say, ‘You have to listen to them.’ I thought, growing up, you drank beer and you bragged. But he said, ‘Listen to them!’” This kind of casual sexism was Matthews’s de facto approach to female guests. He would leer, comment on appearances, then generally disregard what they had to say.

Just before his retirement, he was sidelined at MSNBC after the journalist Laura Bassett reported that in 2016 he had asked her, “Why haven’t I fallen in love with you yet?” In 2007 he told Laura Ingraham, “I’m not allowed to say this, but I’ll say it—you’re beautiful and you’re smart,” and called CNN’s Erin Burnett “a knockout.” His coverage of the 2008 Democratic primary was defined by misogynistic comments about Hillary Clinton that were so egregious that he apologized (though Leibovich later revealed that Matthews believed he had done nothing wrong). In 2016, while interviewing Clinton, he joked about drugging her with a “Bill Cosby pill.”

None of this derailed Matthews’s career, until now. Matthews had the perfect personality for cable’s approach to the news in the post-9/11 era of polarization, which was to bring people on to shout at each other. When the industry started to change, he was already an institution. Crossfire was dead, famously killed by Stewart in one of his signature eviscerations of the cable news set, but Hardball lived on. And Matthews never seemed to care that the ground was shifting beneath his feet—a born yapper and self-proclaimed politics-knower, he treated anyone who thought about politics differently with disdain.

For some, his shtick was charming. Like Joe Biden, Matthews’s mouth always seemed to be miles ahead of his brain. Like Biden, he presented himself as a gruff avatar for the kind of voter Democrats were meant to be winning over—blue-collar, crude, all-American, even if he was really just another creature of the Beltway. Like Biden, he presented himself as an avuncular throwback to a different era.

Eventually the times did catch up to him. Cable news had moved on, increasingly shaped by the conversations happening on Twitter. The discourse had become too jaundiced for the twinkly-eyed Matthews. It had become more serious and more sophisticated, too. In his final opening monologue, Matthews apologized and expressed his faith in the next generation. “We see them in politics, the media, and fighting for their causes,” he said. “They are improving the workplace, we’re talking here about better standards than we grew up with, fair standards.” Matthews was rarely so sincere on his show. But it was too late to start now.