The first time I saw Chinatown, I was about as far as you can get from Los Angeles—sitting by myself in an old movie house in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. This was in the early 1970s, before the era of the multiplex, and movies would arrive in a cluster, spreading across the Cape’s beach towns like sea spray off Nantucket Sound. I was about to turn 13: I did not know anything about Southern California, either its history or its prevailing myths. I had not yet given much thought to water, nor to the conventions of the hard-boiled mystery. I liked crime fiction, though, and I remember the prurient shock of watching as the film’s director, Roman Polanski, who had a cameo as a gangster, sliced open the nose of the detective hero, J.J. Gittes, played by Jack Nicholson. Had I seen Nicholson before? I don’t think so. As for Polanski, I had no idea who he was. What I mean is that my initial experience of Chinatown was about as neutral as it is possible to imagine, far from the way I would later come to think about the film.

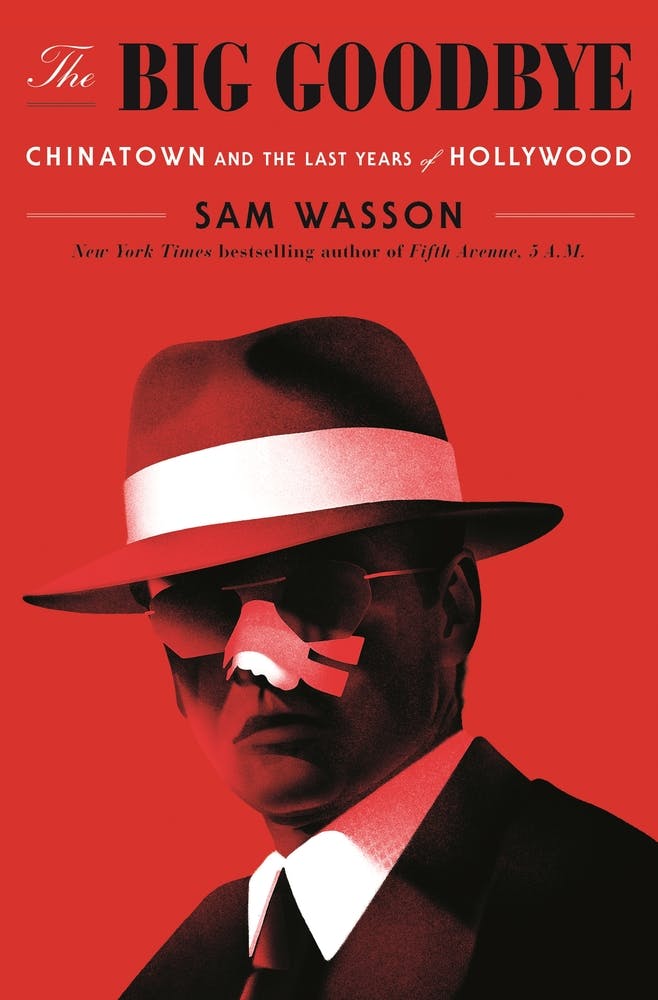

Chinatown, after all, is anything but neutral, nor does it aspire to be. Instead, it represents, as Sam Wasson points out in The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Years of Hollywood, “not just a place on the map of Los Angeles, but a condition of total awareness almost indistinguishable from blindness.” Wasson is referring not only to the motion picture business but also to the psychic terrain of Southern California, its archetypes of boom and bust. He is evoking what Mike Davis, in his 1990 exegesis City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles, identified as “the master dialectic of sunshine and noir.” For Davis, this is a necessary lens through which to reckon with the region, which offers paradisal promise on the one hand and, on the other, chaos and collapse.

What happens when you come to California seeking something—reinvention, say, or self-discovery—only to discover that the baggage you thought you left behind is still strapped across your back? It’s one of the core contradictions of Los Angeles or more accurately of a certain vision of Los Angeles, that of the transplant, the exile from the east. Such a vision has long been attractive to Hollywood for a couple of reasons: Because it makes for a vivid narrative conundrum and also because the studios, or at least their founders, themselves migrated west early in the twentieth century, drawn by the promise of 300-plus days a year of natural light.

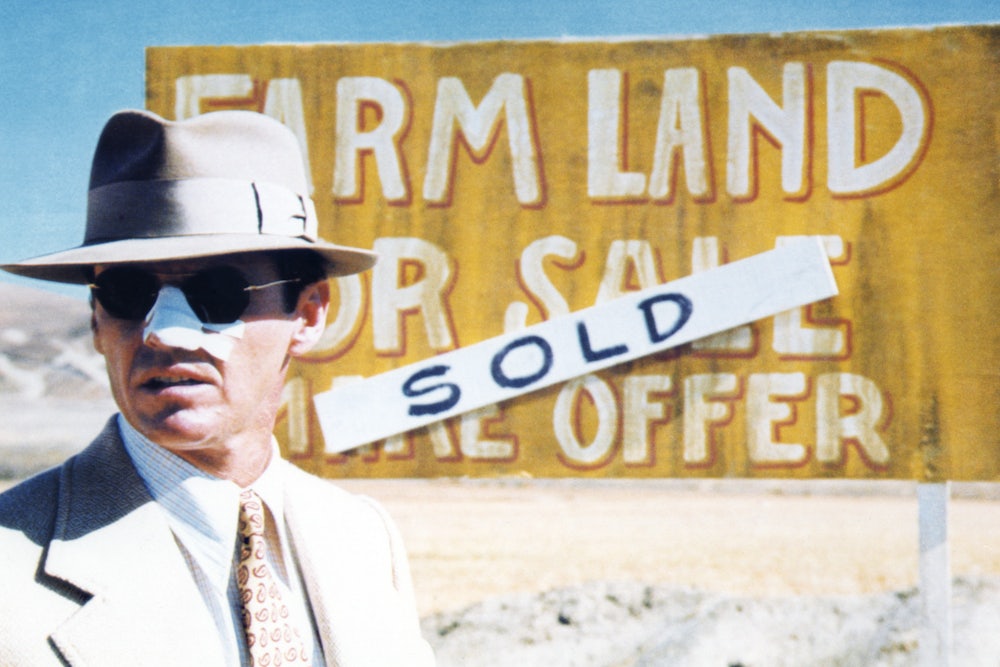

That light is a key, if complicated, component of Chinatown, which attempts to conflate, or integrate, a pair of Los Angeles creation myths. Wasson breaks them down early in The Big Goodbye: First, the cynical sensibilities of novelists such as Horace McCoy, James M. Cain, and Raymond Chandler, who saw beneath the city’s glittering surfaces, its speed and surf and sun—“their nightmare was the city,” he insists—and second, the deeper corruption of what Carey McWilliams called the “Owens Valley Tragedy,” in which an aqueduct was built, diverting water from the Owens River Valley, not to central Los Angeles but rather to “the north end of the San Fernando Valley,” where a cabal of civic leaders, including rail tycoon Henry Huntington and the Los Angeles Times’ Gen. Harrison Gray Otis and Harry Chandler, had secretly bought up a hundred thousand acres. In a very real way, this is Los Angeles’s origin story, a narrative in which private interest, masquerading as public good, changed the landscape of the city for both good and ill. (“There it is. Take it,” William Mulholland, who ran the Bureau of Water Works and Supply, would exhort as water poured into the aqueduct; it is, perhaps, the quintessential statement of Los Angeles, its aspiration and its greed.)

Here we see the history that captivated Robert Towne, Los Angeles born and bred; he wrote Chinatown as a portrait of his hometown. His formulation begins with Gittes, who is retained to investigate Horace Mulwray, a water department engineer, for infidelity, only to discover the conspiracy. “Everybody’s out to make a buck,” Wasson quotes him. “They’re hustling. They’re going to mine it until it runs dry.” The same, of course, might be said of Hollywood, where, by the 1960s, “United Artists and the Mirisch Corporation spent $750,000 for rights to James Michener’s Hawaii and novelists Harold Robbins and Irving Wallace were getting a reported million for the movie rights to books they hadn’t written yet.”

The Big Goodbye—the title is a play on Chandler’s 1953 novel The Long Goodbye—begins in that 1960s milieu and follows an arc through the 1974 release of Chinatown, which Wasson posits as the last real Hollywood movie. It’s a compelling argument, especially when we consider the rise of the blockbuster, beginning with “Universal’s Airport in 1970.” Even as Chinatown was in production, Wasson writes, Fox was earning “monster returns” from The Poseidon Adventure—the second-highest-grossing film of 1972, after The Godfather—and The Towering Inferno, the “top grosser” of 1974. These films were built around a certain rather predictable model: a cast of stars, desperate to survive a cataclysm, which in the former took the shape of a capsized ocean liner and in the latter a skyscraper aflame. What Polanski, Towne, and Nicholson, along with Paramount head of production Robert Evans, had in mind was something far more nuanced, not unlike a novel on film.

The Big Goodbye introduces each of these principals, highlighting their losses as well as their successes. Of particular interest is Polanski, who survived the Krakow ghetto during World War II only to see his wife, the actress Sharon Tate, murdered by followers of Charles Manson in August 1969. Wasson, I think, overstates the effect of the Manson murders, if not on Polanski (for whom such a gloss may be unavoidable), then on the larger Hollywood community. In The Big Goodbye, the killings take on the weight of another creation myth, a driving motivation for Polanski, pushing him ever more deeply into his art.

It’s not hard to recognize the attraction of that narrative, but it also gives the book a kind of built-in closure more ready-made than reality, most likely, would have been. Chinatown, after all—like any creative project—developed incrementally. Some of the most interesting material in Wasson’s book highlights what didn’t work. Towne struggled to finish the screenplay, which he wrote in collaboration with his former Pomona College roommate Edward Taylor; the first draft was 340 pages. (Taylor emerges as a tragic ghost throughout these pages, indispensable to Towne but never given credit for his work.) The idea was to update the Owens River Valley saga to the 1930s and employ it to evoke the city’s corrupt heart. It wasn’t the first time the water story had been reimagined: Mary Austin’s 1917 novel The Ford had shifted the setting to Northern California, while Cedric Belfrage’s Promised Land (1939) used it to make political points.

Towne, however, was after something bigger, and his script needed help. “It didn’t have a single scene set in Chinatown,” Wasson writes. “That wouldn’t fly. Nor would all the civics. Polanski loved the scenes about the water scandal, but ‘in reality,’ he said, ‘the capitalist swindle with the water and land of Los Angeles doesn’t bother anyone.’” Then there was the score, which Towne considered “an abomination.” It had to be redone. The first preview, in San Francisco, “was a disaster.” Although reviews were generally respectful, Pauline Kael called the film “over-deliberate, mauve, nightmarish.… You don’t care who is hurt, since everything is blighted.”

And yet, isn’t that the point? Certainly, it’s the ethos of noir, which Chinatown is channeling, if also challenging, in its way. Noir is about what happens in the shadows. Noir is about what happens when there is no hope left. Noir is a cry of desolation in the face of a universe that is malevolent—or, at best, indifferent. This is why it has long represented Los Angeles’s most enduring vision of itself. “Chinatown isn’t a docudrama, it’s a fiction,” Thom Andersen observes in his 2003 documentary, Los Angeles Plays Itself. “But there are echoes of Mulholland’s aqueduct project in Chinatown.… These echoes have led many viewers to regard Chinatown not only as docudrama, but as truth—the real secret history of how Los Angeles got its water. And it has become a ruling metaphor of the non-fictional critiques of Los Angeles development.”

Andersen’s right, both about the movie and its place in Los Angeles history and culture, the larger myths by which the city lives. Just consider (yes) the use of light in Chinatown, much of which takes place during the day. This is an intentional inversion of noir’s aesthetics, but it works because the sunshine here is tawdry, cheap. I’m reminded of Nathanael West’s The Day of the Locust and John Fante’s Ask the Dust (“If there’s a better piece of fiction written about L.A.,” Towne said of the latter, “I don’t know about it”), which associate the light of Southern California with ennui. “Where else should they go but California, the land of sunshine and oranges?” West asks. “Once there, they discover that sunshine isn’t enough.” Fante is even more pointed:

The old folk from Indiana and Iowa and Illinois, from Boston and Kansas City and Des Moines, they sold their homes and their stores, and they came here by train and by automobile to the land of sunshine, to die in the sun, with just enough money to live until the sun killed them, tore themselves out by the roots in their last days, deserted the smug prosperity of Kansas City and Chicago and Peoria to find a place in the sun.

Here we see the landscape about which Towne is writing. (It’s no coincidence that he would later adapt and direct Ask the Dust.) Here we see the landscape Evans and Polanski and Nicholson aspired, each in his own way, to recreate.

Then, of course, there is the water, which continues to be a master narrative. The Big Goodbye doesn’t have a lot to say about that, and it’s unfortunate, not least because water remains a defining context for the film. Wasson is excellent on the nuances of Hollywood, which is hardly unexpected: He has the access and has written deftly about the industry in previous books. At the same time, he is far too forgiving of Polanski, holding the story of his statutory rape case for the final pages, where it unfolds as afterthought. Still, the problem with Hollywood, as West also noted, is that it is a universe unto itself. That’s what Evans and Towne and Polanski meant to upend. “I decided to do a movie about crimes as they really were,” Towne said, “because the way they really were is the way they really are. I didn’t want to do a movie about a black bird or anything. A real crime, with a real detective.”

And water is the real crime of Los Angeles. It is both the city’s reason for existence and its original sin. I didn’t understand this when I first saw Chinatown in that dusty theater on the other side of the country. I was there to see a film. But Chinatown is bigger than the movies. Rather, as Towne suggests, it is “a state of mind,” the soul of the city captured at 24 frames per second: both narrative and metaphor.