In 2016, Americans who hoped to make sense of Donald Trump’s election could have done worse than turn to a book released earlier that year: Dark Money by Jane Mayer. In this extraordinary—and extraordinarily disturbing—work of nonfiction, Mayer, a veteran investigative journalist, laid bare the tremendous political influence of a handful of far-right billionaires: banking and oil heir Richard Mellon Scaife, chemical industry magnate John M. Olin, electronics barons Harry and Lynde Bradley, and, above all, fossil fuel tycoons Charles and David Koch. To Mayer, these men, and a few others, constituted the “vast right-wing conspiracy” of Hillary Clinton’s nightmares—except their conspiracy wasn’t all that vast. It consisted, she found, of “a small circle of billionaire donors.”

In the years since the publication of Dark Money—and the election of a far-right multimillionaire to the highest office in the land—there has been a boom in books that trace the hidden influence of the uber-wealthy industrialists and financiers who powered the modern conservative movement. Christopher Leonard’s massive Kochland has documented the immense reach and political power of Koch Industries; Nancy MacLean, one of the foremost historians of the Ku Klux Klan, spent a decade writing Democracy in Chains, on the intellectual and institutional roots of the right-wing billionaires’ takeover of the Republican Party; Joshua Green, Jane Mayer, and others have shown how Trump’s team effectively sold their campaign to hedge fund billionaires Robert and Rebekah Mercer, who bankrolled the flailing operation in exchange for control over its messaging and ideological orientation.

Read together, these books undermine the image of a conservative movement guided primarily by organic, popular discontent. The right-wing takeover of government and broad swaths of the media did not happen from the bottom up; rather, it was imposed from the top down, by a tiny collection of super-rich people. Subsequent journalists have documented how supposedly grassroots right-wing movements—from the Tea Party to the Leave campaign in Britain’s Brexit referendum—were secretly bankrolled by a handful of billionaires. So much of what is wrong with the modern world—from the rise of authoritarian leaders to governments’ strident unwillingness to meaningfully address climate change—can, in part, be laid at the feet of just a few individuals who have set the world on fire in order to make more money.

“The earth is not dying,” the folk singer Utah Phillips once said, “it is being killed, and those who are killing it have names and addresses.” Identifying these individuals is essential to understanding the landscape of American politics today, and recognizing the ways they operate is necessary for anyone who wants to challenge their ideas. If the dark-money billionaires thrive on secrecy, these books imply that scrutiny is the first step toward limiting their power.

Shadow Network: Media, Money, and the Secret Hub of the Radical Right by Anne Nelson focuses on an organization that has attracted relatively little attention in popular studies of the right so far. Her subject is the Council for National Policy, a secretive, innocuously named organization founded in 1981 “by a small group of archconservatives who realized that the tides of history had turned against them.” As the demographics of the United States shifted in the decades after World War II—and increasing numbers of people of color, immigrants, queer people, and atheists appeared poised to form a “decisive majority”—these archconservatives believed that their policy priorities would fail at the ballot box. They would need a new set of strategies and they would need to be tightly organized.

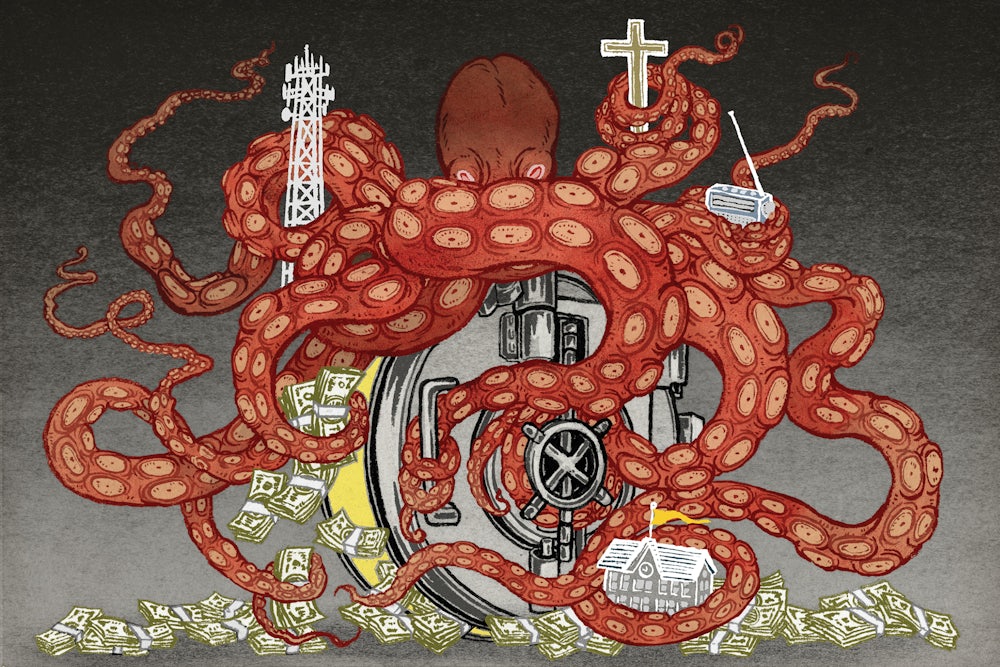

So a small collection of super-right-wing activists created a hub to connect, as one member put it, the “donors and the doers.” Over the next two generations, Nelson writes, the CNP came to function as a “nerve center” for the ascendant conservative movement. In her telling, the council represents a sort of skeleton key for the right-wing takeover, “connecting the manpower and media of the Christian right with the finances of Western plutocrats and the strategy of right-wing Republican political operatives.”

The CNP did not emerge out of nowhere. Nelson, a veteran journalist, traces its origins in part to the Southern Baptist Convention and its internal struggles. Founded in 1845 by breakaway Baptists who seceded from the national church because they disagreed with its opposition to slavery, the convention struggled over the century following the Civil War with how much to accept evolving social norms. As the convention began to grow more liberal in the 1960s and 1970s, a more conservative faction struck back; led by Texans Paige Patterson and Herman Paul Pressler III, a small group of fundamentalists employed get-out-the-vote tactics to engineer a conservative takeover of the convention in 1979. “Patterson and Pressler’s next step was to extend their strategy from church to state,” writes Nelson. “Their plan was rooted in the concept of theocracy: the belief that government should be conducted through divine guidance, by officials who are chosen by God.” As Nelson notes toward the end of the book, both Patterson and Pressler were recently implicated in #MeToo scandals, with Patterson accused of covering up accounts of sexual abuse within his seminary and Pressler accused of committing sexual misconduct himself. But between 1979 and 2019, the “conservative resurgence” they fomented achieved extraordinary success.

In 1979, a Southern Baptist preacher and radio star named Jerry Falwell—vehemently opposed to racial integration and fearing that his segregated academy might lose its tax-exempt status—convened a meeting with some other pastors, as well as the Republican operative Paul Weyrich, co-founder of the influential Heritage Foundation and Republican Study Committee. Out of this meeting emerged a partnership between the conservative pastors and Weyrich’s “team of Washington operatives,” including direct mail and marketing innovator Richard Viguerie. They organized a rally in Dallas for the summer of 1980, which featured a veritable who’s who of the New Right: Weyrich, Falwell, televangelist Pat Robertson, pastor Tim LaHaye (author of the wildly popular, Rapture-themed Left Behind series), and presidential candidate Ronald Reagan; the 24-year-old assistant in charge of logistics was Mike Huckabee, and the crowd included Rafael Cruz, a pastor who “had spent the year steeping his nine-year-old son, Ted, in the doctrine.” Taking in the fervent crowd of supporters, Weyrich “beheld an army of Southern Baptists who could serve as foot soldiers and an electoral base to fulfill his political agenda.” The Dallas rally sparked a political mobilization across the South, Nelson writes, and Weyrich and his pastors launched a major drive to register evangelicals to vote—and to urge them to vote right, so to speak. Their efforts were wildly successful. Whereas just four years earlier, the liberal Southern Baptist Sunday school teacher Jimmy Carter had won the support of fundamentalists, now they turned decisively to the divorced, sometime Presbyterian, Ronald Reagan.

In 1981, Weyrich, Viguerie, LaHaye, Republican functionary Morton Blackwell, anti-feminist lawyer Phyllis Schlafly, oil scion Nelson Bunker Hunt, beer magnate Joseph Coors, and some 50 other conservatives began meeting every Wednesday morning in Viguerie’s handsome Virginia home. It was there that they founded the Council for National Policy. The CNP was deliberately modeled after the Council on Foreign Relations, a prestigious nonprofit think tank with thousands of prominent members and deep connections to America’s foreign policy elite. Similarly, the CNP focused early on international affairs, presenting Oliver North with a special award “for national defense” and inviting far-right Salvadoran death squad leader Roberto D’Aubuisson to give a talk. It also sought tax-exempt status, citing the group’s similarity to the CFR. And though membership in the CNP was likewise highly exclusive and by invitation only, Nelson wryly notes that its 1982 executive committee included Richard Shoff, “former state secretary of the Indiana Ku Klux Klan.”

The CNP began meeting two or three times a year in fancy hotels. Unlike the CFR, it was quiet, highly secretive—refusing even to release the names of its members—and its publications were hard to come by. “There was no pretense of bipartisanship,” writes Nelson. “The CNP was designed to serve as the engine for a radical political agenda. Everything else was window dressing.”

Over the following four decades, CNP members and allies extended their influence—and poured their money—into virtually all facets of American political life. Its members founded vast media empires, including Salem Media Group, Bott Radio Network, and American Family Radio, which Nelson describes as “all but invisible to the urban Northeast” but which have blanketed the airwaves of the Bible Belt and the Plains states with hard-right news and commentary; Nelson mentions segments entitled “Infanticide Adopted by Democrats” and “Homosexuality is the Dividing Line between Light and Darkness,” and one raging against “the demon-god Allah.” These three media behemoths now control hundreds of stations in 46 states, but with a special focus on small and midsize markets abandoned by ABC, NBC, and CBS, and where NPR coverage is sparse.

Meanwhile, CNP members and allies have also come to dominate the world of electoral politics. CNP co-founder Morton Blackwell’s Leadership Institute has trained thousands of conservative candidates, and billionaire members of the CNP, including Wyoming businessman Foster Friess, have bankrolled an entire generation of Republican politicians. Over the past 20 years, CNP plutocrats have allied with the Koch brothers to found faux-grassroots organizations, to fund Republican data firms, and to steer hundreds of millions of dollars to the GOP. Nelson observes that although the Kochs and the CNP disagreed over abortion and same-sex marriage, they “shared a profound faith in petroleum,” and it became clear that the council and the brothers “needed each other”—while the Kochs had billions at their disposal, they “hadn’t a clue how to appeal to the electorate.” The CNP provided the answer. Nelson devotes particular attention to the DeVos family—“CNP royalty”—which united with both the Kochs and the CNP to decimate public schools and unions in their home state of Michigan.

Throughout Shadow Network, Nelson paints an utterly damning portrait of the rise of the modern right, of ostensibly Christian political activists partnering with fabulously wealthy industrialists to effectively take over the country. She identifies the owners, purveyors, and funders of right-wing media, and delves into the political donations of right-wing millionaires and billionaires, which have been enormously effective at lowering taxes and eliminating regulations. While this occasionally descends into what feels like a numbing list of names and organizations, Nelson largely succeeds in throwing light on the vast power of her cast of antagonists.

But if her goal was to identify what she called the “nerve center” or “secret hub” of the conservative movement, she largely fails. This is because, even after several hundred pages, it’s unclear what exactly the CNP actually does. True, its membership has come to include virtually every Republican you’ve ever heard of, from Weyrich to Ed Meese to Kellyanne Conway to Steve Bannon. But Nelson presents no evidence to suggest that the CNP is pivotal to—or even particularly incidental to—its members’ political activities. Their membership seems, rather, more like a stamp of conservative approval, the establishment’s imprimatur for worthy plutocrats. The CNP seems no more the “nerve center” of the conservative ascendancy than the American Conservative Union, Americans for Prosperity, FreedomWorks, the Family Research Council, the National Rifle Association, or any of the alphabet soup of political entities to which pretty much all of the CNP’s members also belong or have ties. Indeed, in January this year conservative power broker Leonard Leo announced the creation of a group called CRC Advisors, which aims to “funnel big money and expertise across the conservative movement”—something that would be fairly redundant were the CNP so central a hub. CNP members and allies may be vital to the right-wing establishment, but that doesn’t mean the CNP itself is.

Perhaps because Nelson herself is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, she believes in the influence of exclusive think tanks with glittering memberships, but her conspiratorial framing significantly undermines the impact of her otherwise trenchant journalism. Perhaps nothing undercuts the CNP’s supposed power more than the swift and virtually complete takeover of the Republican Party and the conservative movement by Donald Trump, surely one of the least biblically minded people alive. As Nelson writes, the CNP’s preferred 2016 Republican candidate was Ted Cruz. And though the CNP effectively aligned itself with Trump following his capture of the party, it seems implausible that it wields as much influence over rank-and-file Republicans as Nelson implies.

Rather, it seems more likely that decades of work by the rich men of the New Right had primed the pump—and here a fossil fuel analogy is particularly apt—for Trump’s complete takeover of American conservatism. By buying their way into the churches, private schools, and public radio antennae of millions of Americans, by decimating public institutions and any semblance of media neutrality, these wealthy conservatives had prepared millions of fundamentalists to support a habitually adulterous, pathologically dishonest reality television personality. The depth and breadth and deliberateness of these millionaires’ and billionaires’ influence—an influence so large that they appear to have lost some control over the monster they have unleashed—is the true revelation here.

Unfortunately, and surprisingly, Nelson lets her antagonists off the hook at the end. In seeking to impart some lesson to her readers, she descends into the mire of both-sides-ism. In her concluding chapter, Nelson expresses disapproval of “coastal Americans who knew every European port of call” but “were often curiously ignorant of their own country.” She reports attending services at charismatic and fundamentalist churches and having liberal friends say to her, “They’re all a bunch of racists.” In response, Nelson offers, “I found that some of the most racially integrated spaces I’ve ever experienced have been in nondenominational megachurches”—as though integrated spaces couldn’t still be racist (in the sense of advocating policies that disproportionately harm racial minorities). She notes that the CNP promotes Martin Luther King Jr.’s niece, Alveda, as a spokeswoman, to stress how “complicated” the CNP’s racial politics are—completely failing to mention the seemingly relevant context that Alveda King is a well-known archconservative activist, who has equated same-sex marriage with “genocide,” denounced abortion as “womb-lynching,” and voted for Donald Trump.

The rise of the far-right is not the fault of Europhilic coastal elites, and the CNP’s politics are not complicated. Rather, the rise of the far-right is the result of a deliberate organizing effort by a small coterie of uber-wealthy industrialists and financiers; the gradual, bipartisan destruction of the New Deal welfare state; the neoliberalization of the postwar economy, with formerly well-paid, unionized employment morphing into gig-ified precarity; and a demographic shift that left many white Americans feeling culturally marginalized, allowing shrewd hucksters to exploit their resentments for electoral and financial gain. The millionaire and billionaire members of, donors to, and allies of the CNP, meanwhile, were happy to play their part in bringing about all of this—so long as it ultimately benefited their bottom lines. Their philosophy is not complicated: It’s greed of such a scale and an intensity that it led them to take a wrecking ball to the most beneficent American institutions; to destroy any lingering shred of independence within the media or the judiciary; and literally to let the world burn—so long as they got that much richer. That isn’t a vast right-wing conspiracy; it’s a small, well controlled, and highly effective one.

Nelson concludes the final chapter of Shadow Network with a call for “us” to “seek common ground.” This is necessary, to be sure, but it is far from sufficient. Rather, the many must take power back from the few. Nelson makes no specific policy or political prescriptions beyond this vague call for unity, but a few spring to mind: a set of rigid campaign finance and anti-corruption laws; a revitalized system of state support for independent media, art, and scholarship; a political movement that can unite the working class against the rich; and, most important, a steep wealth tax.

Although Shadow Network does vitally important work exposing the inner workings of secretive, influential groups, it’s hard to hope for more books in this genre. If we can rebuild democratic institutions and reestablish the conditions that enable them to function, there will be far fewer shadow networks to read about.