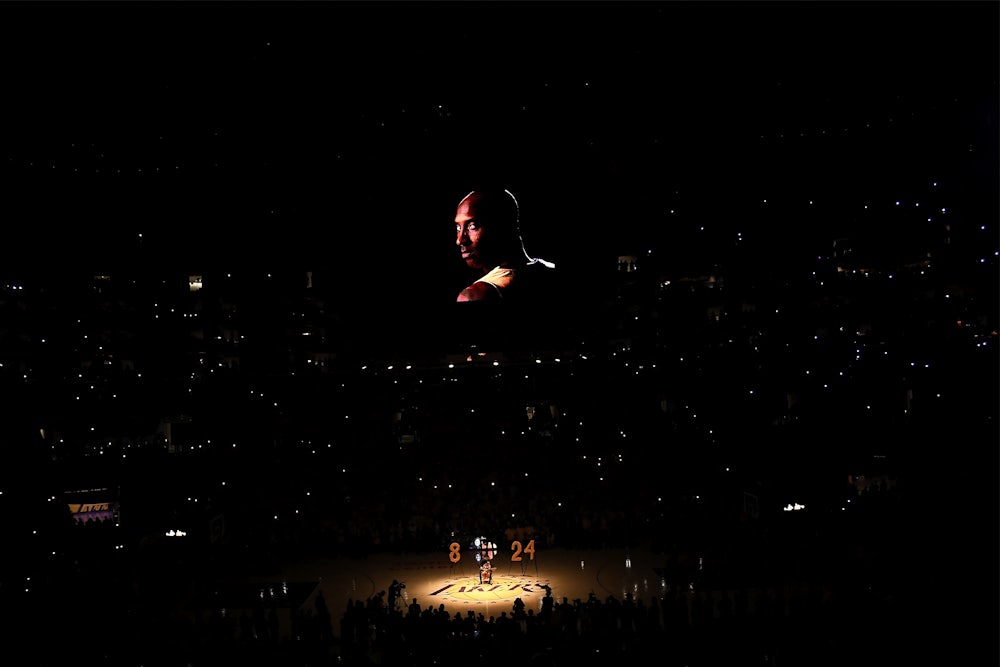

On Friday night, the Los Angeles Lakers offered their tribute to Kobe Bryant, the man whose career first took shape on their courts: Every seat in the Staples Center had his jersey on it. There were musical performances from Usher and Boyz II Men, video montages, a moment of silence, and an emotional speech from his close friend and current Lakers star LeBron James. “This is a celebration of the blood, the sweat, the tears, the broken down body, the gettin’ up, everything, the countless hours,” he said. “The determination to be as great as he could be.” It was an opportunity for the public to collectively grieve, to tell a definitive story. Avoid the mess. But as we’ve seen in the last week of public wrestling with Bryant’s life and legacy, you can’t actually do that. The cracks always show.

Bryant’s death was one of those moments that seemed to stop the world in disbelief. Tributes poured in attesting to how much he meant to basketball, to Los Angeles, to black Gen Xers and millennials who came of age with him and watching him. People shared video clips of his cameos on Sister, Sister, rode waves of nostalgia by chucking wadded-up balls of paper at the trash, yelling “KOBE!” They eulogized him as a father and advocate for women’s basketball, the devastation of those losses compounded by the fact that Gianna Bryant, his 13-year-old daughter, died in the helicopter crash alongside him.

And in what felt like a parallel conversation, there was a remembrance of Bryant as he existed for so many others: another man who hurt a woman and moved on, untouched. They remembered the 19-year-old woman who said that Bryant blocked her from leaving a hotel room in 2003, groped and choked her, then raped her. They recalled the subsequent trial and coverage, how his accuser’s name was leaked to the press while her sexual history and mental health were dissected.

Quickly though, these stories began to collide. As the posthumous hagiography machine began to whirl, there were familiar conversations about respect, legacies, mythmaking, and the “right time” to bring up sexual assault. Obituaries hinted at a “complicated” legacy or made oblique references to “Colorado.” There were mentions of the rape case, maybe, in a quick and tidy paragraph. Anything more would have made the narrative incoherent. Uncomfortable. Distasteful.

The story of Bryant’s life had been written over the course of decades, largely along the same parallel lines. As with so many other powerful men, it was rare to see these two things—beloved men and the harm they’ve done—held in tension for very long. So this ended up being a story about Kobe Bryant and a story about us. How we compartmentalize the people we love or admire. How we don’t know how to talk about sexual violence, and cling to myths about “monsters” and “good guys.” How victims so quickly fade from public view, while the men who victimized them rise in status. We can hardly talk about the strange pain of knowing someone in these ways—a loving father, a supernaturally talented athlete, and an alleged rapist—in life. Why should it be different in death?

Survivors are not a monolith, but for many, the rape case and its reverberations are still incredibly painful. By the time Bryant called a news conference, sitting next to his wife and publicly contesting the charges, the case had already become a national spectacle. It played on historically dangerous stereotypes of black men raping white women and perpetuated harmful ideas about false rape accusations. Ultimately, the woman decided not to testify in the criminal trial, and prosecutors dropped the case. Bryant and the woman would eventually settle a civil case out of court.

This is when we were told to move on. When Bryant retired from basketball, it was seen as “not the time” to talk about the rape case because it was a moment of celebration. It would never actually become the right time, which is a lesson you will learn repeatedly when trying to talk about sexual violence. And so the force of Bryant’s celebrity was relatively unchanged, just usually marked with an asterisk. He was the star you knew, on ESPN, in GQ, on Showtime, but there was also that other thing—a matter to be addressed and quickly moved past.

It can be hard to imagine what better would have looked like. We live in a carceral state that routinely disposes of people, locking them away and calling it justice. So it’s difficult to conceive of atonement outside of carcerality, both from the people who have hurt others and from the media and other ecosystems trying to make sense of them. Restorative justice seeks to bring those who have harmed and those affected by the harm—including the victim, their families, and their larger communities—into conversation with each other, creating processes to rebuild and heal. But these are often smaller, community-led efforts. Victims in high-profile cases often don’t know what to ask for in terms of healing because there is no real map to follow. What does an amends—a public amends—look like at this kind of scale?

But there may have been an opportunity: As the criminal charges were dropped, Bryant issued a statement to address the conclusion of the trial. “Although I truly believe this encounter between us was consensual, I recognize now that she did not and does not view this incident the same way I did,” the statement read in part. “After months of reviewing discovery, listening to her attorney, and even her testimony in person, I now understand how she feels that she did not consent to this encounter.”

This statement is remarkable in that we so rarely see anything approaching this level of public accountability in these cases, but the fact that it’s an anomaly is a testament to how low the bar really is. While the statement may have been a first step toward accountability for Bryant, it also, at least in terms of mainstream response, seemed to put the issue to bed. The very apology that could have been the beginning of public change and healing instead served to silence further conversations. Fans and the media alike largely accepted it as if it was aimed at them; they absolved and forgave and moved on.

And as that happened, there was never a sufficient media reckoning about the treatment of survivors. That would have been too messy, required too much work and perhaps a little introspection. It was better to let the issue fade, an obstacle over which a clean redemption narrative could be crafted. A “challenge” that the superstar overcame on his way to greatness.

Indeed, it often seems as if Bryant’s ability to emerge from this moment was fundamental to the mythmaking. We don’t have to look much further than the #MambaForever tags to see this play out. It’s a special sort of irony that many fans who insisted on leaving this case in the past simultaneously invoked a nickname that was born in the wake of the case itself.

Black Mamba—as a name, as a symbol, as a mentality—was created by Bryant as a direct response to the sexual assault case. It spoke to his ferocity on the court. To his refusal to be “passive” any longer. He also hoped it would serve to “separate the personal stuff” still attached to the name Kobe Bryant. “The whole process for me was trying to figure out how to cope with this,” Bryant told The Washington Post in 2018. “I wasn’t going to be passive and let this thing just swallow me up.”

But as his public redemption narrative picked up steam and his sponsors reappeared, Black Mamba on the court morphed into the deracialized Mamba brand off the court. There were Mamba Shoes, the Mamba Foundation, a partnership with Nike to launch the Mamba League. And then, of course, there was the Mamba Sports Academy, which featured the Mamba team that Bryant coached with Christine Mauser. The team that Gigi Bryant, Alyssa Altobelli, and Peyton Chester played on. The game they were headed to last Sunday when the helicopter went down.

This kind of willful blindness is true across industries but may speak to a way in which sports are covered in particular and the fan culture around players and teams.

Winning seems to absolve many things. So does money. When the soccer club Juventus responded to the news that superstar Cristiano Ronaldo had settled with a woman in a sexual assault allegation years earlier, it tweeted that Ronaldo had shown “great professionalism and dedication” and was a “great champion,” before showing a clip of him scoring a goal and celebrating. In 2015, five years after Steelers quarterback Ben Roethlisberger was accused of two different incidents of sexual assault, a reporter wondered if “the statute of limitations on hating the two-time Super Bowl champion have expired,” noting that “everyone involved has moved on from it” and adding later that Roethlisberger has since become a “family man.” But all of that was almost beside the point: “More than anything,” the piece concluded, “he must continue succeeding, continue pushing forward, and continue delivering success to a Steelers roster that desperately needs him.”

In all of these cases, the half-finished—or never started—conversations around harm and healing are left stranded with soft-spoken apologies, contrite press conferences, settlements, and NDAs. They become footnotes to the legacies of great men.

In Bryant’s case, the post-basketball chapter of his life offered a more mellow and personable public image. He seemed to be at peace in retirement. His announcement that he was leaving the NBA had become an Oscar-winning short film. His foundation was growing, and, above all else, he had his family. He had his girls. His relationship with Gianna and her emergence as a basketball player brought him back to the game in a new way. He coached her team, took her to games, and followed her lead, becoming an unexpected champion of the women’s game at both the collegiate and professional level.

While a few writers voiced frustration with Bryant’s smooth public transition as a champion of women—particularly the way the WNBA and sports media amplified him and rewarded him for it—the overwhelming and enduring images of this part of his life are of him courtside with Gigi at a UConn game or coaching her as she shot a fadeaway in the same way he did. More than anything, it’s perhaps this piece of his life that is hardest to hold with the Bryant of 2003, the man who allegedly assaulted a 19-year-old and moved on.

It’s incoherent, putting pieces of a puzzle together that don’t fit, jamming them, or discarding one or the other. But we need to hold them. Even if they are heavy. This is the work. These are the conversations we should push ourselves to have—and to listen to those already having them—to sit in the tension. For the same man who gave so much to the game of basketball, who championed women’s sports and loved his daughters fiercely, also harmed a woman. That is not exceptional, or a matter of celebrity—it’s a fact of life and also of death.

And while broader conversations about public figures, reverberating harm, restorative justice, and public amends are invoked while trying to make sense of men like Bryant, this is not just a matter of celebrity. People are grappling with contradictions laid bare by the messiness of mourning and memory all the time. Just like there are people watching the sweeping tributes for Byrant and pained by the hagiography, there are people sitting at smaller memorials, at family funerals harmed by the loved one being eulogized. There are folks trying to figure out how to publicly mourn someone they still had private tension with. The awful finality of death leaves so much unresolved. It leaves the threads of narratives abruptly dangling.

Earlier this week, on the side of a building in Austin, Texas, an artist painted a mural in remembrance of Bryant. That same night, someone added the word “rapist” next to his face. Almost as soon as it appeared, it vanished. Painted over. Muted. A glimpse of the legacy Bryant leaves behind.

A full portrait of a life is jagged and messy. It’s incoherent. Made more so when mythmaking attempts to smooth it out, and when memorials seek to absolve instead of reckon with. These pieces of a person may seem disjointed and distant, but in reality they are interwoven and overlapping. Disentangling that is a shared responsibility, something we owe to each other to get right. But by the time the eulogies are being written, it’s often too late, and all that’s left is contradicting emotions we have as we sort through the pieces. There are lessons in the life and death of Kobe Bryant. We still might not be ready to learn them.