If you wanted to boil down conservatism to a single anodyne formula, it might be “reverence for the past.” But reverence, as opposed to respect or understanding, often requires a selective memory: Inspect an image too closely, and flaws that seemed accidental might appear pervasive, even essential. While we usually think of writers and intellectuals as transmitting knowledge, the role of conservative intellectuals is just as often to enable those selective forgettings that make the persistence of their movement possible. From this need comes the birth of something perhaps new in the history of human folly: a knowledge class whose very existence comes from its ability to not-know.

It’s to this kind of return to this haze or amnesia that Ross Douthat almost calls the nation in The New York Times. In one representative column published last fall, “Can the Right Escape Racism?,” Douthat fondly recalls that the conservatism of the second Bush managed to “partially suppress” the “racially polarizing controversies” of the early 1990s and hopes for a return to that better era.

The premise here is clearly flawed: What was suppressed, or forgotten, has returned with a fury. The combination of political legerdemain and the natural improvement of conditions that Douthat credits for a “less racialized” conservatism obviously did not do the trick: Trump happened. When Douthat writes that the “agenda” of the “younger Bush was consciously designed to win over at least some minority voters and leave the Lee Atwater era behind,” he declines to note that Lee Atwater, who ran the infamous race-mongering Willie Horton ad in 1988, did his bloodiest work for the elder Bush.

To be sure, among today’s intellectual defenders of the modern right, Douthat is on the more perspicacious end of the spectrum. Undaunted by their failure to affect any electoral outcomes, the coterie of thinkers and writers who have coalesced loosely around the “Never Trump” movement have staked their careers on the notion that Donald Trump is an aberration, a kind of eruption of atavistic “tribalism” from the prehistoric past, instead of the result of a historical narrative that’s hiding in plain sight for less blatantly self-interested interlocutors.

But as the novelist-cum-political candidate Upton Sinclair noted long ago, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” And so recent months have seen an efflorescence of publication launches on the American right devoted to the larger intellectual project lurking behind the Douthatist reflex: namely, to write Trumpism out of the recent history of the conservative movement. And true to that tacit mission, their fledgling publications dare to imagine a conservative movement primed to govern without the polarizing, vulgar, and bigoted figure of Donald Trump at its helm.

In early 2019, the former editor in chief of The Weekly Standard, William Kristol, helped launch The Bulwark, a digital journal with a blunt Never Trump mission. In an interview, the site’s founder, Charlie Sykes, an erstwhile Wisconsin conservative talk-radio host, explains that The Bulwark seeks “to create a home for rational, principled, fact-based center-right voices who were not cowed by Trumpism.” And last fall, Kristol’s successor at the Standard, Stephen F. Hayes, threw in with National Review senior editor Jonah Goldberg to debut The Dispatch, another publication bound and determined to conquer the post-Trump frontier for respectable conservative thought leaders of the old school. Hayes told the news site Axios that The Dispatch would focus on reporting, adding that while its political outlook would be “unapologetically conservative,” the site would require “fact-based arguments.”

These efforts have met with understandable skepticism. The immediate predecessors of the Trump age on the intellectual right were, after all, something shy of Burkean guardians of hallowed norms, customs, and tradition; no, the story of recent right-wing politics has been a nearly unrelieved study in bomb-throwing and icon-smashing, from the ’90s distempers of Gingrichism on through to the neoconservative capture of foreign policy in the George W. Bush administrations to the intersecting bigotries of the Tea Party and Birther movements in the Obama age. To truly brand an honest inquiry into conservative intellectual life as “Never Trump,” such an effort would also have to show how Trumpism is in fact a culmination of long-unruly, demagogic, and cynically jingoistic tendencies in the house of the American right.

Instead, the dominant image of conservatism in Never Trump media outlets is an incongruously decorous one. Sykes argues that “Trumpism represents a repudiation of much of the conservative tradition” rather than its natural culmination. Bill Kristol, in National Review’s 2016 “Against Trump” issue, advanced a similar get-thee-behind-me message to the ascendant Trumpist ideology: “Leo Strauss wrote that ‘a conservative, I take it, is a man who despises vulgarity; but the argument which is concerned exclusively with calculations of success, and is based on blindness to the nobility of the effort, is vulgar.’ Isn’t Donald Trump the very epitome of vulgarity? In sum: Isn’t Trumpism a two-bit Caesarism of a kind that American conservatives have always disdained?” This sniffy contempt is a little bit difficult to take from the man who aggressively promoted Sarah Palin, a vulgar proto-Trumpian demagogue if there ever was one, for vice president.

It’s a colossal understatement to say there’s little organic curiosity—and even less donor money—on the American right to lay bare these sorts of ironies. So to begin to unravel the manifold contradictions and memory lapses entailed in the revisionist intellectual projects of Never, post-, para-, and pro-Trumpism, it’s necessary to do what so few right-wing thinkers are disposed to do these days—namely, to learn some hard lessons of history.

It’s been a longtime malady of American intellectuals of all ideological persuasions to mistake the activities of a handful of little magazines for the bold stirring of a mass political consensus. That’s been especially true for the published work of conservative intellectuals. Since the birth of the modern right after World War II, its self-appointed leaders, intellectuals, policy professionals, and media personalities have never been able to consistently exercise any control or even influence over any mass constituency. Their pet policies have gained little public support. At best, these leaders have been able to first articulate, with varying degrees of accuracy, some inchoate dissatisfaction, or to hitch themselves opportunistically to waves of popular discontent. For the most part, however, they are merely the sideline interpreters of political and social events—and even then, they often see the world through a glass, tinted darkly by ideology or tendentiousness.

This combination of impotence and myopia helps explain some of the mainstream movement’s spectacular political failures of the recent past—as well as the inability, even with the total GOP capture of three branches of government, to end Obamacare (itself not a particularly popular program). The institutional right’s erratic-at-best engagement with popular politics also explains a host of similar fundamental miscues, such as the Cato Institute leadership’s total misreading of the Tea Party as the long-hoped-for dawning of a libertarian mass movement, instead of its virtual opposite: the first rumblings of a lurch into reactionary and racially inspired nativist confrontation that would eventually break the free-market consensus in the conservative coalition.

These failures of basic apprehension underline, in turn, another core paradox of intellectual conservatism: For the conservative elites’ self-advertised preoccupation with ideas and the ennobling Western tradition of critical inquiry, the American right has always been, as people as different as Lionel Trilling and Pat Buchanan have recognized, more an affair of the viscera than the head. And the minds of the American right, as they pursue the movement’s self-appointed mission to preserve the traditional basis of American society and (in its more grandiose states of transport) Western Civilization, have never been able to come up with a consistent idea of what this is. As a result, the quest for a coherent intellectual lineage on the right gets very tangled very quickly. In the movement’s ranks, you’ll find the uneasy coexistence of people who trace the essence of the country back to Hamilton through Lincoln alongside cult worshippers of Jefferson and the Confederacy, capitalists alongside agrarian traditionalists, radical individualists and communitarians, localists and nationalists. Nor do the differences within the movement become any less blurry as they multiply. Conservative intellectual debate pits theoreticians of the predominance of executive power against tribunes of legislative power, apostles of highbrow elitism against enthusiasts for iconoclastic cultural populism, champions of the Middle Ages against the die-hard defenders of Enlightenment reason, the most bloodthirsty hawks against most uncompromising doves, etc.

And yet, despite their sometimes-bitter internecine feuds, this motley assortment of thinkers was able for half a century to maintain a more-or-less self-conscious identity in American public life. It’s true that a belief in cultural and moral decline often unites the right—but even here, there’s very little agreement on the exact date of the catastrophic moment: Was it the 1960s, the New Deal, the 1860s, the political philosophy of Machiavelli or Hobbes? Or did everything start going to hell with the advent of the Enlightenment? Or again (as recondite conservative thinkers such as Eric Voegelin maintain) with the rise of gnosticism in the second century A.D.?

These ideas are bewilderingly various, but also perennial. Richard Weaver in the late 1940s identified fourteenth-century nominalism, a movement holding that concepts are just names and not reflective of underlying reality, as the point at which Western Civilization went off the rails. Rod Dreher revives Weaver’s thesis (apparently without attribution) in his 2017 book The Benedict Option. There are two books named Suicide of the West, one written by National Review founding editor James Burnham in the 1960s, and one written by former National Review editor Jonah Goldberg in 2018. They have nearly opposite theses: The fatal wound for Burnham stems from liberalism’s pusillanimous and self-undermining nature; for Goldberg, it resides in our collective failure to stick by the founding premises of the liberal tradition.

The fact of the matter, then as now, is that ideas on the right are not so much irreconcilable as they are irrelevant. More than principle, the presence of threat and an enemy is the most important driver of right-wing energy, and since the end of the Cold War, the hunt for enemies has become ever more desperate. That’s especially been the case from the moment since the wars on terrorism and Iraq failed to coalesce the movement—let alone the country—into any viable political coalition for any sustained interval beyond the moment they launched.

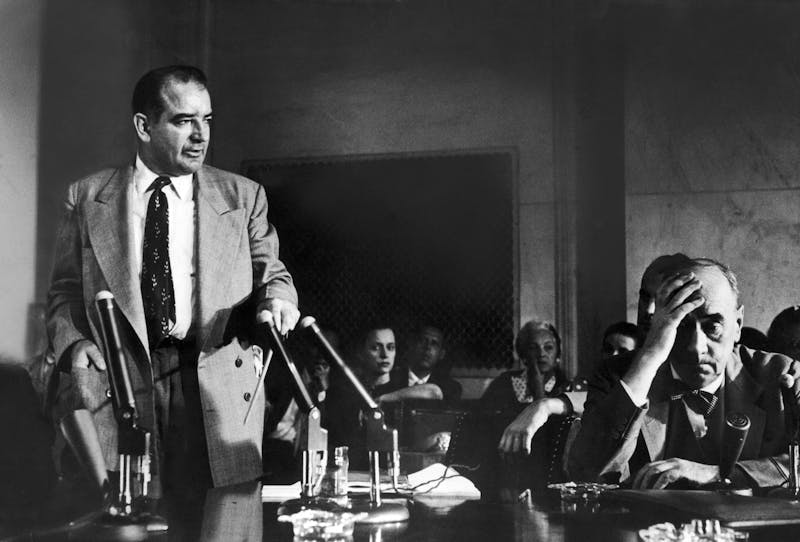

Still, the struggle continues. The conservative intellectual has traditionally achieved his greatest cachet as an apologist of just this sort of existential combat. Ever since the height of the mid-century anti-communist frenzy, the right-wing intellectual’s charge has been to lend the imprimatur of cultural seriousness to political confrontations and mass movements not of his own making. It was only after the ebbing of Joseph McCarthy’s highest point of power, in 1954, that William F. Buckley Jr. and L. Brent Bozell published McCarthy and His Enemies. In that faux-daring apologia, the authors admitted the abundant weakness of McCarthy the man, and even called his actions “reprehensible,” but argued fiercely for the cultural-therapeutic value of McCarthyism as a movement. Here, Bozell and Buckley insisted, was an idea born out of political conflict—and a valuable “program of action against those ... who help our enemy.” Warming to their subject, they also hailed Tail Gunner Joe’s unhinged crusade as a “weapon in the American arsenal” against Communism, alongside the atom bomb, and called for men of “good will and stern morality” to “close ranks” around it.

While dramatizing the practical political irrelevance of ideas, the McCarthy legacy on the right also highlights the second rule governing the modern conservative movement: the indispensability of the mob and its demagogues. Again and again, conservative intellectuals have fastened themselves like barnacles onto demagogic movements such as the ones led by McCarthy or Trump; if they don’t, they risk cutting themselves off from mass politics entirely. That specter always means doom for right-wing intellectuals, since it effectively dispels what small amount of influence they can have, as well as their subscribers, viewers, and donors.

As a result of these ungainly movement dynamics, conservative intellectuals could offer their benedictions and apologias but have been less easily able to excommunicate heretics. It was after much hesitation and several false starts that Buckley and National Review decided, for respectability’s sake, to purge Robert Welch and the John Birch Society in 1965. And when they finally did, they received a deluge of subscription and donation cancellations, as the historian Nicole Hemmer points out in her 2016 book Messengers of the Right: Conservative Media and the Transformation of American Politics. After Buckley composed a mammoth cover essay at the end of 1991 accusing Buchanan of anti-Semitism, the publication tacked back toward him by urging disenchanted conservatives to cast a “tactical vote” for the bigot just months later, once the insurgent Buchanan candidacy mounted a surprisingly fierce primary challenge to incumbent President George H.W. Bush. And, more recently, after its stentorian “Against Trump” issue before the 2016 primaries, the magazine adopted what can most charitably be called an agnostic stance before the once-despicable specter of Trumpism ascendant, taking care to balance critiques of Trump with broadsides aimed at his critics. (The preponderance of the names on the cover of the anti-Trump issue are now, if not outright supporters, qualified defenders of Trump.)

These patterns repeat themselves over and over in elite circles of conservative opinion-making. In last summer’s National Conservatism Conference in Washington, D.C., the movement strived to find a new container to replace the worn-out idea of pragmatic movement-intellectual “fusionism” on the right, and tried out the scarcely less abstract and broad catchall term of “nationalism” as a framework for collaborative unity.

The coinage had certain virtues of candor. Nationalism is perhaps closer to the essential core of the type of politics practiced by conservatives for more than half a century, because it is more explicitly about defining the boundaries of a polity against an Other. This is perhaps part of a growing self-consciousness among right-wing ideologues about the true nature of their politics.

Amid these increasingly deranged conditions of discourse, those who are foolish enough to actually believe in the principles they evince find themselves isolated and under attack, often as insufficiently true believers in the cause. Matt Labash, a former national correspondent for The Weekly Standard, bitterly recounts what it’s like to find yourself on the business end of a right-wing enemy hunt: “How do you feel about Sarah Palin? About the Tea Party? About Trump? If you were skeptical about any of these things at the time, you were a RINO, a cuck, or whatever other dopey term of art the rageisphere comes up with to mean ‘not one of us.’ When in truth, most mass enthusiasms are worthy of skepticism.”

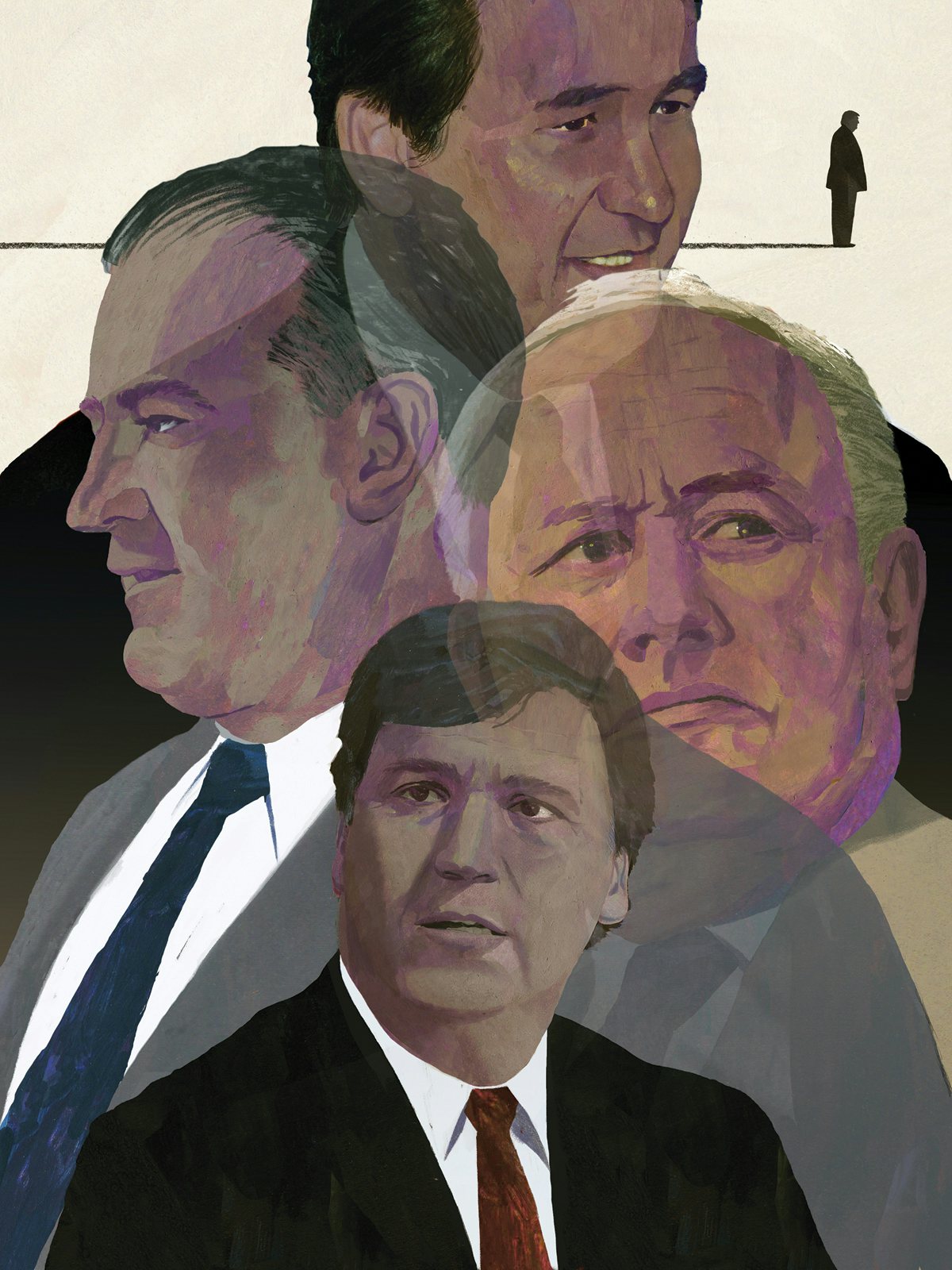

There’s perhaps no better illustration of the life cycle of the conservative elite than the fate of The Weekly Standard and its former star writer, Tucker Carlson. Under the promptings of the Trump movement, Carlson has transformed himself from journalist and commentator to demagogue—or as Andrew Ferguson, his former colleague at The Weekly Standard, told me, “the Father Coughlin of the twenty-first century.”

The Standard, a center of the fading neoconservative consensus in and around Washington, was one of the main mouthpieces of the pro–Iraq War camp. Its final editor, Stephen F. Hayes, had attempted to prove, against overwhelming evidence, the collaboration of America’s enemies Saddam Hussein and Al Qaeda, an effort that culminated in Hayes’s 2004 book The Connection. During the 2016 election cycle, the magazine became a premier outlet of Trump criticism on the right—at which point its subscribers began repudiating the publication en masse.

Ferguson, a former Standard senior editor, recalls being on the magazine’s annual cruise for its subscribers. In 2015, not long after Trump had announced his candidacy, most passengers aboard the ship shared the acute anxiety that the Standard’s editorial brain trust was expressing over Trump’s possible success. But within a year’s time, Ferguson said, everything had changed: “They were ready to throw us overboard. It was open disputation around the clock. People cornering you and saying, ‘Why the hell don’t you lay off Trump?’... People like winners, they like victory. And they thought Trump had brought them a victory and it was our responsibility to do everything possible for him.” The moral of all this was unmistakable, and bitter: “The divorce between the people who run those magazines and who actually write the stuff that’s in them and the people who were the presumed constituency has been pretty ugly and radical.”

Other publications have tried, with varying success, to adapt to drastically changed circumstances on the intellectual right. The American Spectator, a free-swinging magazine that had incubated the careers of Ferguson and fellow Standard editor Christopher Caldwell in the 1980s and ’90s, once followed the cues of Buckley’s National Review in policing boundaries of respectable right-wing discourse. In the early ’90s, for example, it featured an attack on Pat Buchanan by a young David Frum (the former arch neocon and W. speechwriter who’s reinvented himself as a Never Trump contributor to The Atlantic). Come 2018, however, the Spectator featured a piece by Emerald Robinson arguing that the GOP elites failed in their campaign against Trump because of the cultural disconnect of the pundit class, who “skew Jewish and agnostic and libertarian,” from the “overwhelmingly Caucasian and Christian” Republican base.

When the Standard failed to get in line, its days were numbered. At the end of 2018, the magazine’s billionaire owner, Phil Anschutz, pulled the plug and folded the Standard’s subscriber base into the list for the reliably pro-Trump Washington Examiner. Bereft of a political or financial basis, it was doomed; its former staffers have been forced to scramble to find new homes. While Kristol joined Sykes’s The Bulwark, and Hayes and Goldberg launched The Dispatch, ex-senior editor Chris Caldwell has made a space for himself at the Claremont Institute, promoting a sort of Trumpism-without-Trump nationalist conservatism.

The fortunes of ex-contributing editor Tucker Carlson have followed a somewhat different path. After Carlson’s written work broke out into the mainstream, he launched a career in TV punditry, notably cohosting CNN’s barking-heads franchise Crossfire in the early 2000s.

After Carlson netted a reasonable-conservative time slot at MSNBC that flamed out in short order, he landed a spot on Dancing With the Stars, where he was voted off after the first episode. During a speech at CPAC in 2009, Carlson sounded very much like the serious right-wing journalist Ferguson wanted him to be. Rather than endlessly lamenting liberal bias in mainstream news outlets, Carlson argued, the conservative movement needed to found credible journalistic institutions of its own. The crowd didn’t take to the counsel—nor, over the long haul, did Carlson. The right-wing news site he went on to found in 2010, The Daily Caller, was a far cry indeed from a conservative New York Times: Its scoops largely fell flat, and, like most other ideologically driven web operations, it soon specialized in producing opinion and takes.

Under Carlson’s watch, the Caller was also infiltrated by the racist far right. There had been persistent rumors in conservative media about Katie McHugh’s and Scott Greer’s connections with the then-largely unknown white nationalist Richard Spencer. Carlson turned a blind eye to such fraternizing—and to much of the Caller’s daily editorial work. McHugh left for Breitbart, where she was eventually fired; Greer had earlier relinquished his post at the Caller prior to the revelation that he wrote for Spencer’s Radix Journal. (And as Hannah Gais’s reporting for Splinter last August has revealed, they were not the only alt-rightniks to burrow into the Caller: At least two more staffers had ties to the white nationalist movement.)

Just after Trump’s election, Carlson returned to TV with his own Fox show. The fall of Bill O’Reilly pushed him into Fox’s prime time 8 p.m. slot, and Tucker Carlson Tonight quickly became the network’s biggest draw. While the well-born Carlson had been for most of his career a fairly mainstream conservative, he has used his bully pulpit on Fox to transform himself into a full-throated right-wing populist, inveighing against unrestrained capitalism while also flirting with open race-baiting.

In July, Carlson was invited to give a keynote address at Washington’s National Conservatism Conference. A combined effort of mainline institutions like the American Enterprise Institute and more heterodox voices on the right, the conference sought two chief aims: to provide an overarching intellectual framework for the nationalist right and to distance the nationalist conservative movement from the explicitly racist far right. One of the organizers, Israeli political theorist Yoram Hazony, barred the participation of VDARE’s Peter Brimelow and several other white nationalists. Despite such precautions, however, the old dynamics of movement conservatism soon took center stage, when University of Pennsylvania Law School professor Amy Wax announced in a speech on immigration that the country would be better off with “more whites and fewer nonwhites.” Faced with this reminder of the issues animating the Trumpist right outside the conference room, several conservatives proceeded to defend Wax’s comments in an effort that rapidly went from desperate to dishonest.

Carlson’s keynote, delivered in somewhat manic tones between fits of giggling, showed an easy familiarity with the demagogues’ tool kit: The pundit’s hand gestures while speaking have even begun to resemble Trump’s. The identification of the enemy was the overriding theme. Carlson identifies the new enemy as corporations that adopt liberal social politics and the “woke” left, rather than the state: “I was trained from the youngest age, from a pup, to believe that the threats to liberty came from the government, because the Soviet Union was our model.” Now, however, Carlson contends that the principal threats to honest American liberties “come primarily from companies, and not the federal government.”

In a way, Carlson’s path is just a recapitulation of the entire story of the Fox network. Well before Carlson launched his career as a TV pundit, Fox’s efforts to promote straight news with a conservative angle largely failed to gain market share on anything like the scale that its most loudmouthed opinion shows did. Ferguson recalled the difference between the network at its inception and its current state: Fox “wasn’t anything like what it is now. It kind of became the caricature that the left had of it. I think Ailes seriously wanted to start a news network that would be entertaining and would have all the kind of corner cutting that you expect from television journalism, but it would still be a legitimate news operation.... I think he kind of abandoned the idea of it being a conservative version of legitimate news. And so he let people like Hannity and O’Reilly run wild.”

In fairness to Fox producers, some version of this same Faustian bargain runs through most of today’s right-wing outposts of political discourse. And even when conservative institutions and media outlets don’t partner outright with demagogues and bigots, they seek other strategic accommodations to the forces of blatant reaction, via think-tank sinecures and grant money. For example, the Claremont Institute, which was founded by followers of Leo Strauss’s student Harry Jaffa, recently provided a fellowship to Jack Posobiec, who’s eagerly granted platforms to alt-right bigots and promoted hoaxes and fake news including the Pizzagate conspiracy theory. (The hits keep coming: A blog at Claremont ran a piece that was devoted to giving a high-intellectual veneer to labeling David French “a cuck.” Claremont has also given space to Curtis Yarvin, a.k.a. Mencius Moldbug, the neo-reactionary crony of Peter Thiel, and several weeks later the institute published a piece by one “Bronze Age Pervert,” a troll about as bizarre as his name suggests.)

Ever since their first assaults on New Deal liberalism, conservatives told themselves that once the state was hollowed out, civil society would naturally follow a path that protected their interests. Corporations are some of the most trusted institutions in our society, but conservatives are now loudly dissenting from most corporate-brokered models of social consensus. So the conservative movement rank and file is taking its cues from leaders such as Trump and Carlson, and training their ire fully on the lead institutions held to be the most powerful gatekeepers in American civil society: corporations, the press, and universities.

When conservatives like Buckley and Bozell defended McCarthy—and when they later attacked the counterculture and the New Left—they called for social conformity and “responsible” limits to the open society. Now, by contrast, conservative intellectuals find themselves defenders and allies, in the name of free speech, of the most distasteful by-product of the market society: the déclassé, bohemian mob leaders of the alt-right. These figures traffic in a politics of acute and unquenchable resentment, arising out of “failure in professional and social life, perversion and disaster in private life,” to quote Hannah Arendt on the types of malcontents who furnished fascist movements with their leaders.

Perhaps pro- and para-Trump conservative elites have not fully realized they are making common cause with full-blown cynics and nihilists. Perhaps they truly don’t grasp that their provisional allies on the alt-right are not simply against the present disposition of American institutions, but also devoted to demolishing the restraining influence of standards and institutions altogether. Or perhaps, long saddled with the wounded self-consciousness of outsiders, conservative elites now view the mob as their cousins, sharing a common resentment against the mainstream society from which they, too, feel excluded. At a minimum, the ease with which figures now pass back and forth between the worlds of the alt-right and the conservative sanctums of elite discourse means that we have diminishing cause to distinguish the one world from the other anymore.

As a result of all these deranging forces on the Trumpian right, the future of conservative institutions that try to bypass (let alone eclipse) the alliance between mob and elite is doubtful. Conservative intellectuals who try to preserve their honor and refuse association with the quasi-criminal demimonde called forth by Trump will find themselves returned to the condition of the Old Right before it hitched itself to McCarthy: cloistered in small magazines, arguing mostly with one another, with little to no influence on mass politics. It’s hard to avoid the reflection that this demoralizing state of exile was what prompted Jonah Goldberg to name his podcast The Remnant, after Albert Jay Nock’s idea of an elite that would keep the flame of wisdom alive within the destabilizing, ignorant convulsions of political life in mass society. This is also why the popular prospects for The Dispatch, Goldberg’s fledgling venture with Hayes, seem dubious. (And indeed, so far The Dispatch appears quite modest: more of a blog or newsletter than a full-fledged publication.) The experiences of the Standard and The Bulwark have, in strikingly different compasses, pointed up the limitations inherent in advancing a vision of right-wing politics that at once refrains from reflexive Trump-bashing while pursuing impartial reporting and analysis. The intellectual market on the right has only smiled on a style of discourse that’s pretty much the polar opposite of such an approach: purely partisan diatribes that reinscribe the American right’s sense of utmost cultural exclusion even at a moment of peak political power. In other words, the Goldberg-Hayes venture is trying to replicate a model of conservative discourse that’s failed again and again on the American right over the past 70-odd years.

Of course, Goldberg’s powers of analysis are limited, and particularly so when it comes to interpreting the conditions that now prevail on the American right. For example, in a recent rejoinder to a piece by Vox writer Jane Coaston on racism on the right, Goldberg protested that Trump’s racism has more in common with “some cops, cab drivers, and doormen from my youth, not Oswald Spengler or E.A. Ross. In his views, he’s closer to Andy Sipowicz in the early seasons of NYPD Blue than George Wallace.”

Even a cursory knowledge of American political history would tell you that George Wallace made significant inroads in Northern cities among the very sorts of people he’s describing, so it’s difficult to understand what point, if any, Goldberg is making about the role racial animus plays on the American right. To say Trump doesn’t sound like Oswald Spengler, meanwhile, is not exactly an enlightening point: It’s simultaneously obvious and ignores the fact that an Olympian theorist like Spengler was less dangerous than the cruder, more popular figures on the far right.

In many other ways, the ghosts of Weimar hover behind the right’s growing embrace of friend/enemy politics. Here the guiding authority isn’t a Spengler or an E.A. Ross, but rather the influential German political theorist Carl Schmitt. For Schmitt, the contest between existential enemies was the very essence of political life. By contrast, Schmitt argued, the haggling and intrigues of mere parliamentary democracy were a “depoliticized” shadow of true politics, which always involved the possibility of actual killing. Vanguard intellectuals on today’s right such as Adrian Vermeule, a law professor at Harvard, now openly invoke Schmitt’s influence on their own work, and it’s hard to overlook the echoes of his thought in right-wing New York Post opinion editor Sohrab Ahmari’s call for an end to “depoliticization” and for a “politics as war and enmity.”

Schmitt had aligned himself with the Nazis for a time, before he was gradually pushed out of a central role in the party. (What need could there ultimately be for a legal scholar, after all, in a criminal regime?) Schmitt’s devotion to Nazi ideology was never all that certain, as the Nazis themselves realized: He had previously worked, and cultivated friendships, with Jewish scholars and even called for the German government to ban Hitler’s party in the early 1930s. But it was Schmitt’s combination of careerism as well his amoral theory of politics that drew him into the Nazi movement, which allowed him to broadcast his anti-Semitic views more widely; politics, for Schmitt, is largely the pursuit of war by other means. The most compelling judgment that political actors exercise within any political system is the designation of enemies. Leaders arbitrate just who is potentially an existential threat and who is a friend arrayed against the same threat; as a result of this irrational vision of leadership, truly political decisions are independent of any aesthetic or moral criteria.

As long as members of today’s conservative elite share Schmitt’s opportunism, and continue endorsing a Schmittian politics of enmity that overrides any principle or standards, there’s no telling how far they will go. It’s possible that they’ll wind up in a prolonged state of internal cultural exile, as other modern movements of the right have. They could also pay a severe price for their opportunism if they allow themselves, as Schmitt did, to go along with a totalitarian movement, or a reasonable American facsimile of one. It profits a man nothing to give his soul for the whole world … but for a show on Fox?

Then again, there may be no particular moment of prophetic reckoning for the latter-day apostles of Schmittian politics. Schmitt had a decent career after his time with the Nazis, and his reputation today barely suffers for it. It’s just as likely that his intellectual heirs in and around the Trumpified conservative movement will do just fine. They can dust themselves off, make half-hearted mea culpas, and get ready to hitch themselves to the next war, the next reign of terror, or the next demagogue that comes down the pike. But what’s also unclear, and far more pressing, is whether the country and its institutions can survive the right’s shameless pandering to the mob and its ever-shifting hunt for enemies.