From time to time in the Trump era, Republican members of Congress have found themselves stricken with blindness, deafness, illiteracy, or some combination thereof. Their affliction tends to manifest whenever President Donald Trump and his allies do something troubling. They claimed that they didn’t watch coverage of a rally where his supporters chanted “Send her back!” about an immigrant member of Congress and asserted that they had never even heard of Roy Moore during his scandal-ridden Senate campaign in 2018. The symptoms are most severe whenever those members run into reporters in the hallways of Capitol Hill. Suddenly, GOP lawmakers profess that they have not seen a TV, or checked the internet, or participated in the Industrial Revolution.

The Senate’s impeachment trial is a useful antidote. It is unlikely that 67 senators will vote to convict Trump and remove him from office, largely because that number can only be attained with the help of 20 Republican senators. I wrote on Tuesday that this process is also a trial for the Senate as an institution, as well as the senators themselves. Ignorance is not a legal defense, and if nothing else, the House managers have made it impossible for their colleagues to deny that they knew what happened.

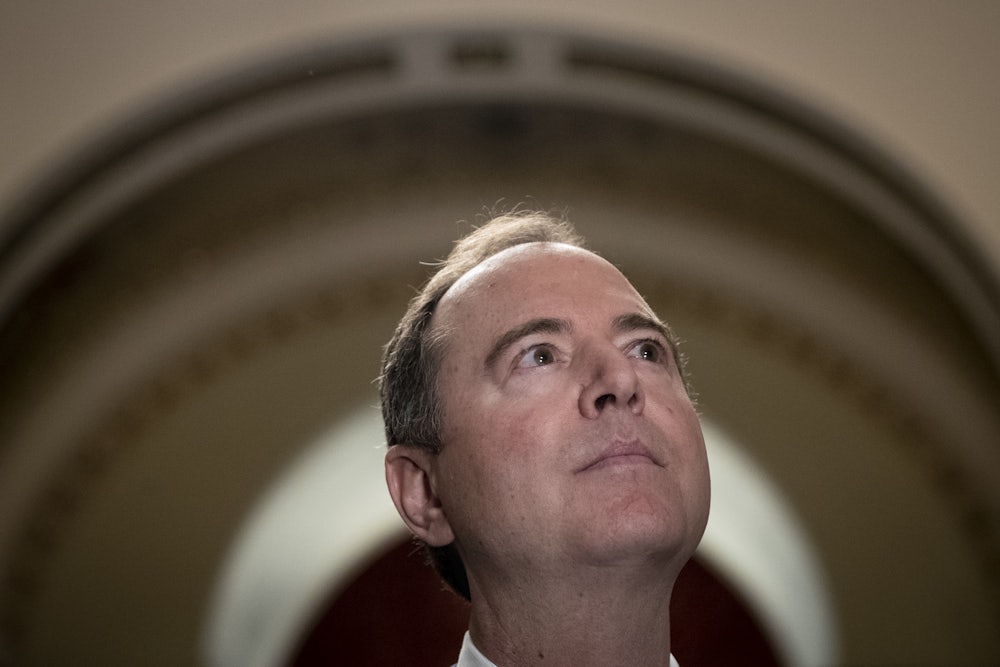

Day two of the trial began on Wednesday with the opening statement from California Representative Adam Schiff and the other six managers who act as the president’s effective prosecutors in this trial. Schiff, a former prosecutor who now chairs the House Intelligence Committee, spent more than two hours delivering an able summary of the case. He received effusive praise from legal observers on Twitter. Even South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham, one of Trump’s most obsequious allies in Congress, told Schiff later that he did a “good job” and was “very well-spoken.”

Schiff is not a particularly dramatic or emotive speaker. He instead punctuated his staid remarks with video clips of the president and his associates in their own words, as well as portions of testimony from the witnesses who appeared before Congress last fall. The weaving together of their words and his analysis worked well. Perhaps the most dramatic moment came when he played footage of the infamous moment last October when Trump publicly declared that not only should Ukraine launch an investigation into the Bidens, but China should do the same.

At the time, Trump’s comments drew a murmur of criticism from GOP lawmakers, though most still kept quiet. Schiff brought it front and center. “This should concern all of us,” he said. “It’s a confirmation not only of the scheme to pressure Ukraine to help his political campaign, but a clear sign that the president believes that these corrupt acts are acceptable. A president this unapologetic, this lawless, this unbound to the Constitution and the oath of office must be removed from that office, lest he continue to use the vast presidential powers at his disposal to seek advantage in the next election.”

One weakness in the House’s case is that it doesn’t have all the documents and evidence that might be relevant, thanks to the Trump administration’s unbending defiance in the face of multiple subpoenas. Schiff managed to turn this liability against Trump. At one point, he discussed a State Department cable sent late last August by U.S. diplomat Bill Taylor about the scheme. “Would you like me to read that to you?” Schiff asked the senators. “I would like to read it to you right now, except I don’t have it. Because the State Department wouldn’t provide it. But if you’d like me to read it to you, we can do something about that.”

Will it make a difference? Michigan Representative Justin Amash, an ex-Republican lawmaker who voted to impeach Trump in December, suggested that some of Schiff’s presentation might be news to those present. “Based on my experience with Republican colleagues in the House, I suspect that many Senate Republicans are hearing the facts of this case for the first time,” he wrote on Twitter on Wednesday. If true, that would be a damning indictment of Senate Republicans and their fundamental ability to do their job.

An epiphany still remains unlikely. These are the same senators, after all, who voted late Tuesday night and early Wednesday morning to not call witnesses or seek additional evidence. And they are the same legislators who have largely avoided public critiques of the president for three years, out of either agreement or electoral self-preservation. If they ultimately vote to acquit the president, they will only make undeniable what was already apparent: that congressional Republicans are not hapless bystanders in Trump’s plots against the American democratic system, but willing and conscious co-conspirators to them.