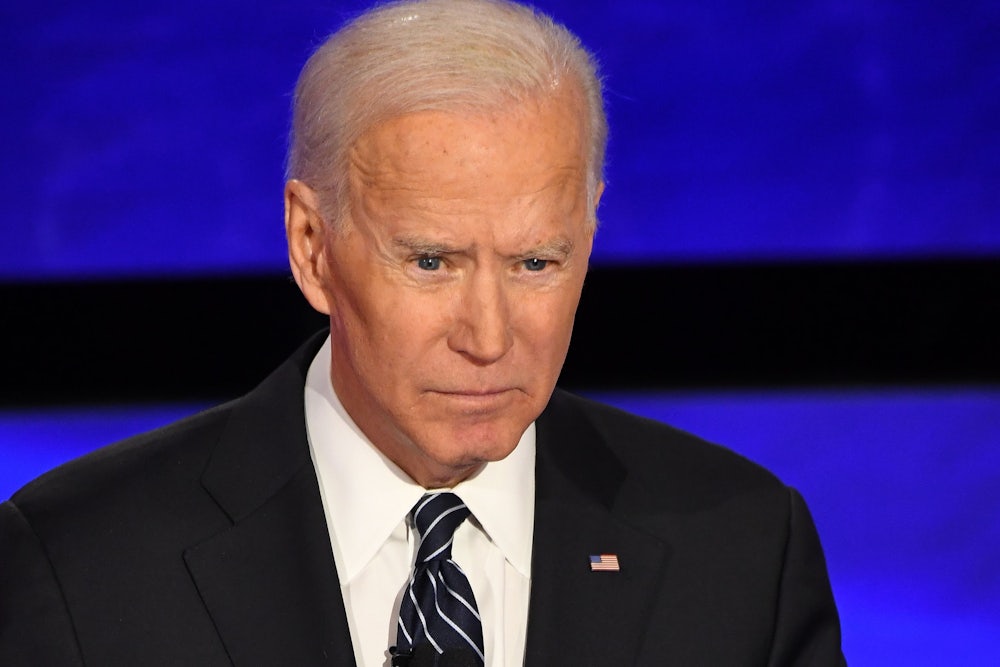

Joe Biden may have stumbled into supporting one of the most radical climate proposals of the primary.

The moment came in an interview, published Friday, with members of The New York Times’ Editorial Board, which has been conducting a series of sit-downs with Democratic primary candidates. After a rambling discussion of the recently passed United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement’s enforcement mechanisms (“I’ve not read them yet, OK?” Biden responded), New York Times writer Binyamin Appelbaum asked Biden if he thought “Democrats should vote for an agreement that does not affirm the Paris accord and does not contain any binding commitments to deal with climate change?” In essence, he was asking whether Democrats should vote for a deal like the USMCA, which many Democrats supported this past week in the Senate and Joe Biden backed on the campaign trail.

“Look,” Biden answered vaguely, “it’s like saying would you sign an agreement with Turkey on a base closure because it didn’t have that in it? It depends on if it’s related to climate. Absolutely they should be part of it.”

He pointed to China. “China, in fact, in their ‘Belt and Road’ proposal is in fact exporting more dirty coal around the world and is subsidizing more than anybody in the world.” That’s not all true. While China is by far the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter and dominant coal producer, Australia is its top coal exporter. The United States is fourth. China is ninth. What Biden was likely referring to was China’s generous state subsidies for coal and large-scale financing of coal-fired power plants across multiple continents.

Fact-checks aside, Biden then tottered into an interesting, innovative thought that bears roughly zero resemblance to the trade agreement he was presumably defending:

[W]hat we should be saying to them is, you keep your agreement on the climate accord, which you signed up to. If you don’t, you will pay a price for it. You will not be able to sell product here. And organize the world to make sure that no, they couldn’t sell product anywhere. To make sure that they in fact have a requirement to stick to what they committed to.

When Appelbaum noted that Canada is a major fossil fuel exporter too, Biden remained resolute on this apparent proposal for sanctions on anyone not meeting Paris Agreement commitments: “That’s what we should be doing to everybody in the world.”

What about the U.S.? Were Biden’s principle of climate sanctions applied for all fossil fuels out of step with Paris Agreement goals (to which Biden pledged to recommit), such a rule would almost certainly place a major damper on U.S. fossil fuel production.

While this isn’t completely out of step with the policies outlined on Biden’s website, he hasn’t previously discussed many of the details of this part of his platform. Emphasizing the need to stop China in particular from “subsidizing coal exports and outsourcing carbon pollution,” Biden’s stated platform pledges to make any bilateral U.S.-China climate agreement contingent on their cutting fossil fuel subsidies and lowering the carbon footprint of Belt and Road projects. He would also impose border adjustment fees on carbon-intensive goods, preventing “other nations” from “undermining our climate efforts.”

Laudably, Biden’s platform further calls for eliminating fossil fuel subsidies across the G20. Yet experts say living up to the Paris goals will require more direct policies to stanch America’s domestic fossil fuel production, much of it destined for export. The Production Gap Report released this year by the United Nations Environment Program, Stockholm Environmental Institute, and several other research bodies finds that the world’s governments are on track to produce 50 percent more fossil fuels than is consistent with capping warming at 1.5 degrees Celsius, and 120 percent more than is consistent with a two-degree rise. Another report by Oil Change International found that the U.S. is set to account for 60 percent of the global increase in oil and gas production between now and 2030—drilling plainly incompatible with the Paris Agreement’s goals of keeping warming “well below” two degrees Celsius.

The Times interview also represents a big departure from policies Biden was associated with prior to the current election cycle. Domestic crude oil production increased by 77 percent during Biden’s time as vice president, and the U.S. Energy Information Administration projects that it’ll reach record highs through 2021. That’s due in no small part to the lifting of the crude oil export ban under the Obama administration in 2015, which boosted the fossil fuel industry by opening up expansive new markets for its products.

“I’m glad to see Biden acknowledge trade in fossil fuels as a climate issue. There is some promise in using trade measures to bring fossil fuel production in line with climate limits. And of course that is not limited to coal from China, or oil from Canada,” Stockholm Environmental Institute U.S. Senior Scientist Peter Erickson wrote to me in an email. “Shouldn’t that same logic be applied to oil and gas exports from the U.S.?”

Were Biden to faithfully follow his commitment to the Paris goals and plan as outlined to the Times, he would push for not only a rapid, managed decline of the fossil fuel industry but the creation of a binding international trade regime with the power to materially discipline any nation—including the U.S.—failing to scale back emissions and carbon-intensive exports.

This would be a game changer in American foreign policy, essentially upending the world order as we know it in the interest of building a low-carbon world. It would also be a far cry from his old boss’s approach. At a Shell- and Chevron-sponsored gala last year for Rice University’s Baker Institute in Houston, Obama happily took credit for inconsistencies in his administration’s handling of climate issues. He said he was “extraordinarily proud of the Paris accords” before bragging about how much oil his administration helped extract. “You wouldn’t always know it, but it went up every year I was president,” he exclaimed, referring to domestic oil production. “That whole, suddenly America’s like the biggest oil producer and the biggest gas—that was me, people.”