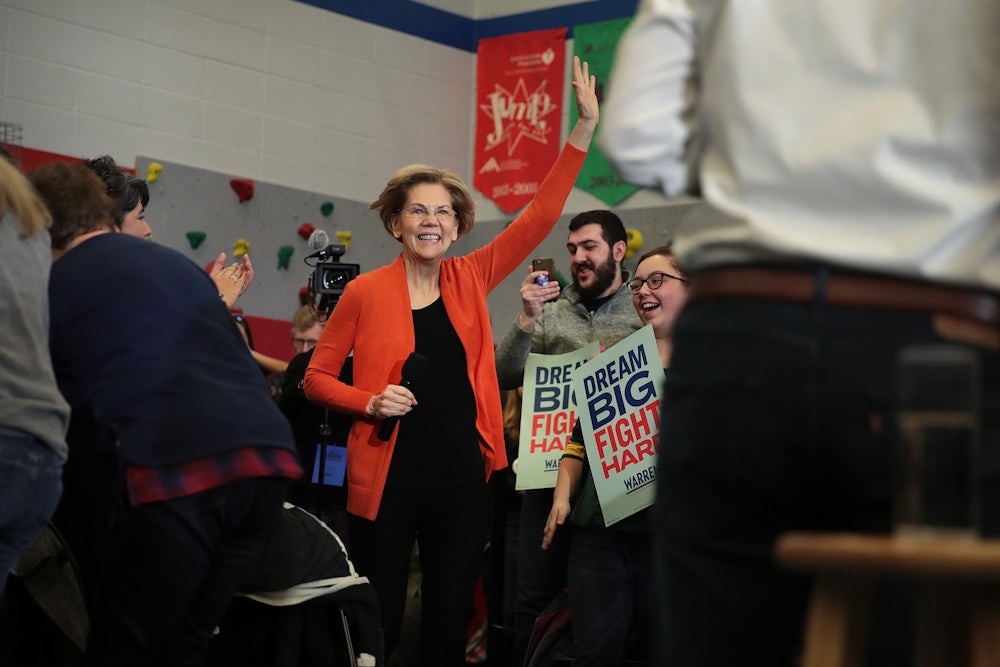

Elizabeth Warren still bounds on stage at campaign events like she just heard the starter pistol, often shouting “Woo-hoo” for emphasis.

She still has the most compelling stump speech of anyone in the Democratic field, explaining in Mason City, Iowa, on Saturday that her life arc, “like most Americans’, is not a straight-line story.” More than half the crowd at recent Warren campaign events stood in line for what the candidate called “the all-important part of democracy—selfies.” (In fact, in Milford, New Hampshire, late last week, more than two dozen Warren fans also waited to pose for photos with the family dog, a golden retriever named Bailey.)

And Warren is running second in the influential Des Moines Register survey. (True, a Monmouth University poll, released Monday, showed her placing fourth in Iowa with 15 percent, but, based on the margin of error, she could be as high as second.)

But for some reason the press is treating Warren like yesterday’s news, a shopworn contender whose strengths as a candidate pale next to the steadiness of Joe Biden’s support, the supposed Bernie Sanders surge, the novelty of Pete Buttigieg, and the underdog appeal of Amy Klobuchar. There is almost a sense that the well-funded Massachusetts senator has been stricken with the Kamala Harris “I’ve fallen and I can’t get up” syndrome.

The truth is that media narratives are the most volatile part of the Democratic race. Every blip of news prompts journalists to recalibrate the odds on the Democratic nomination fight, knowing, even as they do, that these campaign developments are as evanescent as a light dusting of snow. Every cable TV panel discussion, every print reporter desperate for an angle, every polling analyst out to update the odds needs a reason to explain why today is different from yesterday—even when it isn’t.

Of course, things are very different for Warren than they were even just a few months ago. After running a nearly flawless campaign during the spring and summer, Warren lost her footing in the political quagmire known as “Medicare for All.” It began when, in an October debate, Warren ducked and dodged questions about whether the government would need to raise taxes on the middle class to pay for universal health care. Then she frightened mainstream Democrats in October with a $20.5 trillion financing plan over 10 years. And in November, she antagonized left-wing Democrats by opting for a two-step legislative approach that would begin with a version of the public option embraced by most of the other candidates in the race, apart from Sanders.

This series of missteps undermined her carefully cultivated image as an accidental senator animated by idealism instead of crass political considerations. She had backed off from Sanders-like purity on Medicare for All seemingly because she feared the political reverberations. And her candidacy suffered for it.

That reversal alone might be a valid reason to critique Warren’s political judgment. But every one of the leading Democratic candidates is flawed in some way or another: Joe Biden can be dismissed as too old-fashioned, Bernie Sanders as too shrill, and Pete Buttigieg as too green. Yet among the top four, only Warren has become the forgotten candidate in this race. That may be because the press pack loves hard numbers like polls and financial filings, and not long after Warren’s Medicare for All fiasco, Sanders, Buttigieg, and Biden all outpaced her in fourth-quarter fundraising. Of course, she only fell short of Buttigieg and Biden by less than $4 million, but it was enough to feed the media narrative that the Harvard law professor turned Massachusetts senator had fatally lost her momentum.

This is the moment when I feel compelled to quote the famous 1928 New Yorker cartoon caption: “I say it’s spinach, and I say to hell with it.”

Warren still boasts formidable advantages going into the Iowa caucuses on February 3. The most important edge is that Warren has put together—in the estimate of both rival campaigns and neutral Iowa experts—the best team of organizers. As a senior figure on the Warren campaign told me in an interview, “We made a big bet that organization matters. We invested in Iowa first, and we invested early.”

Organization ranks up there with turnout as a political cliché. But as political scientist David Redlawsk, an expert on the Iowa caucuses who now teaches at the University of Delaware, put it, “We always say organization matters. But in the case of the Iowa caucuses, it is particularly true with so many moving parts in the caucus room itself.”

Anyone who shows up to one of Iowa’s more than 1,600 precincts on election night can switch their allegiances if the person they initially supported fails to clear 15 percent in the first round of caucusing. This dance of democracy as campaigns vie for second-chance caucusgoers is dramatic to watch. And it benefits candidates like Warren, who has a cadre of experienced precinct captains behind her.

Although Warren’s senior campaign staff never imagined it when they were setting up her Iowa operation early last year, organization may play a particularly crucial role for the four senators in the race (Warren, Sanders, Klobuchar, and Michael Bennet) if they are confined to the Capitol for the duration of Donald Trump’s impeachment trial. What we may end up with is a de facto MSNBC primary, as the four senators compete for cable TV hits, in an attempt to reach Iowa voters at the end of each day’s impeachment proceedings in Washington.

None of this is to say that Warren will win the Iowa caucuses. The Des Moines Register poll, conducted with CNN and Mediacom, found that a stunning 60 percent of would-be caucusgoers say that they could still end up changing their minds. Talking with caucus experts, estimates of turnout on a cold Monday night in early February range from about 225,000 (less than on Barack Obama’s victory night in 2008) to a record 300,000, which would be roughly half the Democrats in the state. And even if pollsters could somehow pinpoint how many Iowans will turn out on caucus night, remember that 60 percent could still switch to another candidate. Three weeks out, you can be certain that anyone who offers a glib prediction for the Iowa caucuses doesn’t know what he or she is talking about.

Jonathan Morrison, a 45-year-old commercial drone operator who lives in Mason City, is my emblematic Iowa Democrat. He has been canvassing for Buttigieg and has a Buttigieg sign on his front lawn. But he was curious enough about Warren that he joined a crowd of 300 who came out to see her in Mason City.

“I’m not sure wavering is the right word for my situation,” Morrison said when I asked him about his support for Buttigieg. “It’s just that it’s so close this year that I want to make sure that I make the right decision.” Morrison can see a case for Warren: “She represents for me a fearlessness to take on the issues that she feels passionate about—banks, corporations, and the one percent.”

In an Iowa race this muddled, it was perhaps inevitable that tensions would spill over to the campaigns. This past weekend, Politico published a Sanders campaign script sniffing at Warren’s supporters as “highly educated, more affluent people.” In a calibrated, more-in-sorrow-than-in-anger tone, Warren responded by saying, “I was disappointed to hear that Bernie is sending his volunteers out to trash me.” Then, on Monday, CNN claimed that Sanders told Warren in 2018 that he didn’t believe a woman could win the presidency—a story that, although Sanders quickly denied it, soon became the day’s tit for tat. (On Monday evening, Warren made the accusation herself.)

Such self-destructive sniping will only intensify as we near caucus night. It’s enough to make every Democrat feel a bit saddened by the departure from the race, on Monday, of Cory Booker, who preached the gospel of “love.”