“I do think that the debate rules have been deeply destructive to the field and to my campaign. It has made it hard to raise money because people view the debates as sort of a proxy for success.”

The speaker was Colorado Senator Michael Bennet, during an interview with me in Washington last week. But the same could have been said by fellow exiles from Thursday night’s debate stage: New Jersey Senator Cory Booker, former Department of Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julián Castro, and former Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick.

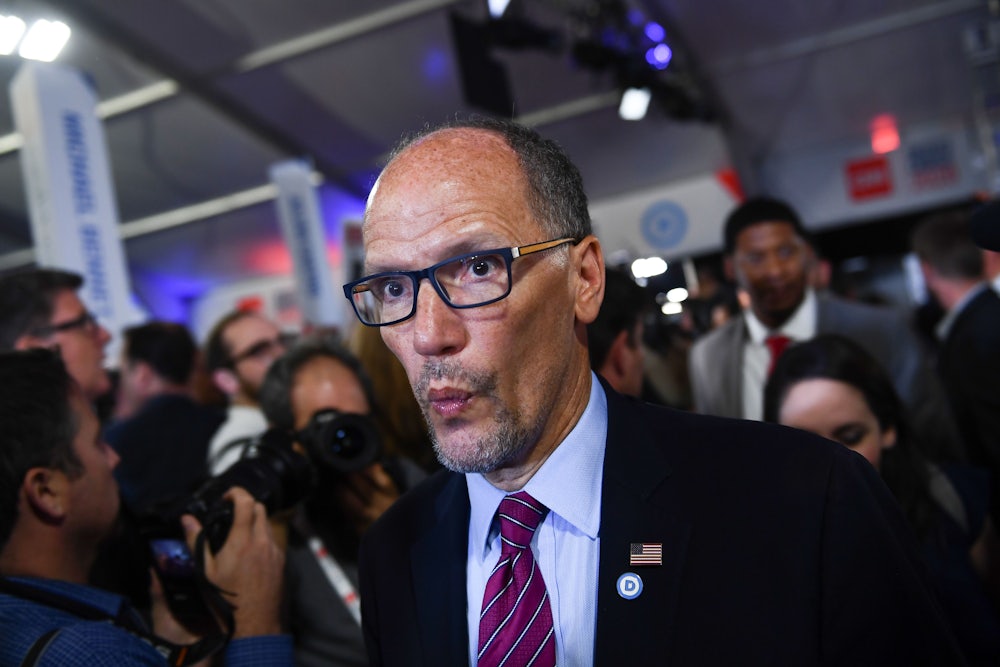

In an impressive feat for a party that prides itself on its diversity, Democratic National Committee Chair Tom Perez’s rigid debate rules have rejected both African American candidates still in the race and the only Latino contender; Andrew Yang will be the only nonwhite candidate on the stage tonight in Los Angeles. At a time when most Democratic voters are still working through their candidate lists with the avidity of a six-year-old before Christmas, the DNC has turned otherwise serious contenders into political un-persons.

On the surface, the rules to qualify for this week’s debate seem reasonable: at least 4 percent support in four qualifying national polls and 200,000 individual donors. But they have resulted in candidates obsessing about polls months before anyone votes and, to meet the DNC’s arbitrary donor threshold, running Facebook ads trolling for $1 contributions.

Perez blames the candidates for not qualifying, rather than the rules that he created. Exuding innocence, Perez told The New York Times, “I’m not doing the polling. I’m a huge fan of Cory Booker.... And if voters are disappointed that he hasn’t qualified, then when they answer the phone, they need to express their preference for Cory Booker.”

In truth, the major reason to arbitrarily limit the number of candidates on the debate stage is to cater to the networks and their ratings-driven quest for drama. But how did the Democratic Party as a whole benefit from large chunks of the prior debates being devoted to hard-to-follow squabbles over Medicare for All?

In Perez’s defense, during the 2016 campaign, Bernie Sanders supporters had almost a religious belief that Debbie Wasserman Schultz, as party chair, gift-wrapped the nomination for Hillary Clinton. The most incompetent Democratic chair in recent memory, Wasserman Schultz would have been hard-pressed to rig an election for a third-grade hall monitor. Yes, Wasserman Schultz was heavy-handed in her support for Clinton, but there is scant evidence that Sanders could have won the nomination.

Perez’s solution was to create debate rules so arbitrary that nobody could blame him for anything. The result has been absurd spectacles like ego-tripping billionaire Tom Steyer spending a fortune on Facebook ads so that he could find more than 200,000 Democrats so gullible that they would send campaign contributions to a self-funding billionaire. But the larger problem is the weight that Perez’s rules place on polls, particularly national polls.

The entire logic behind devoting the whole month of February to opening-gun caucuses and primaries in four small states is to let the voters winnow the field of presidential contenders. Underperforming candidates routinely withdraw after the Iowa caucuses, as Joe Biden did in 2008.

But in place of early-state voters (including a heavily African American electorate in South Carolina and a significant Latino vote in Nevada), the debate rules now cull the herd. Two sitting governors (Steve Bullock and Jay Inslee), a senator from New York (Kirsten Gillibrand), a former governor (John Hickenlooper), and a political meteor from Texas (Beto O’Rourke) have all surrendered to the inevitable without a single vote being cast.

Kamala Harris, by the way, had qualified for the December debate. She dropped out earlier this month for the old-fashioned reason that she was out of money and couldn’t see a path to the nomination.

It is fashionable to argue that only losers fail to mobilize a national following seven weeks before the Iowa caucuses. But since the days when Eugene McCarthy stunned Lyndon Johnson amid the snows of New Hampshire in 1968 and a little-known governor named Jimmy Carter swept the opening contests in 1976, Democratic voters have reveled in surprising the handicappers.

One simple rule change would solve the majority of the problems surrounding the debates: Give an automatic seat on the stage to any Democrat who has won a statewide election or served in the Cabinet in the last 10 years. Only true outsiders like Yang and Steyer would have to prove that they have enough of a following to qualify for the debate stage.

If it requires two debates to accommodate all the eligible candidates, it is a small price to pay to return to voter sovereignty. The TV networks would reluctantly go along with two debates because politics has become a major profit center for them since 2016. Already, almost all the 2020 candidates (both on and off the December stage) have called upon the DNC to loosen the rules to qualify for the January 14 face-off in Des Moines, the last debate before the Iowa caucuses.

It is probably too late for Bennet to have a shot at the nomination, regardless of the January debate rules. His campaign put out a memo this week asking for $700,000 to pay for a bare-bones TV ad campaign in New Hampshire, a state where he is banking on a historic come-from-behind upset.

During our interview, Bennet said, “I will confess that I got into this race late. And that’s my responsibility.” Part of the delay was caused by successful treatment for prostate cancer, and part was due to indecision over running.

But after a decade in the Senate, Bennet is widely considered one of the most respected and thoughtful Democrats in Washington. A top fundraiser for Pete Buttigieg said to me, “If you took a secret ballot of Senate Democrats as to who would make the best president, Bennet might well win. It’s a shame that he’s not even allowed to debate.”

“I know it when I see it,” Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart said in a 1964 decision on pornography. The same judgment is usually obvious about presidential candidates. Cory Booker is serious and Marianne Williamson ludicrous. A self-confident party chair would make that determination without resorting to premature polls and lengthy lists of penny-wise donors online. Too bad that Tom Perez has been more concerned with avoiding blame than with guiding the Democratic Party in the most important nomination battle of the century.