In 2019, Netflix’s Our Planet was widely praised for pushing the limits of the nature documentary genre. Instead of artfully depicting wild animals and glossing over the threats they face, Our Planet repeatedly reminded viewers that human activity was destroying the world depicted on screen. The show’s radicalism had limits, however: Turn the sound off, The Atlantic’s Ed Yong noted, and the series looked just like its peers: a cavalcade of charismatic creatures in magnificent settings. “It’s like watching an American drug ad during which a voice-over reads out lists of horrific side effects over footage of frolicking, picnicking families,” he wrote.

For those who would prefer to maintain that civil distance from an ever-grimmer reality, Bil Zelman’s book, And Here We Are: Stories From the Sixth Extinction, published by Daylight Books this month, will be a bitter pill to swallow. While the environmentally conscientious filmmakers behind Our Planet hoped to save nature by highlighting its beauty, Zelman aims to communicate what damage has already been done through a visual language that matches the severity of the situation. “I really wanted to do the opposite of what nature programming does,” he told me. “I enjoy those shows, but they’re fantasies. I wanted to tell a darker story.”

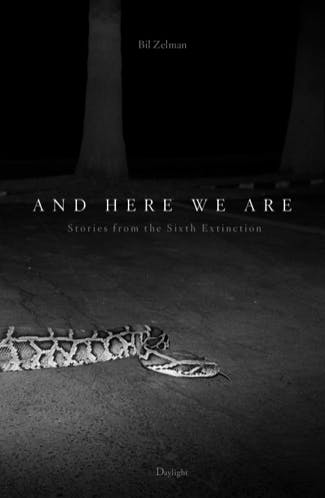

He means that both figuratively and literally. Zelman shot all his photos at night, using studio lights and flashes to illuminate and isolate his subjects. The resulting resemblance to Weegee’s film noir shots of New York crimes and calamities is no accident. Zelman sees the Sixth Mass Extinction—the human-driven “biological annihilation” that scientists say is sending extinction rates skyrocketing for only the sixth time in the planet’s history—as an atrocity. His book functions as a collection of ecological crime-scene photos.

Environmental degradation has long served as a rich topic for photographers. But unlike Edward Burtynsky, for instance, whose recent Anthropocene Project centered the human in a world out of whack—aerial views emphasizing the scale of human settlements and industry—Zelman offers a refreshingly ecocentric perspective. While signs of human civilization are not entirely absent from And Here We Are, they are far from the primary focus. Instead, Zelman’s vision of ecological calamity considers first and foremost the experiences of individual plants and animals living on an increasingly alien planet. In one photo, a Burmese python—a species native to Southeast Asia—slithers through a parking lot in the Florida Everglades, where its population has exploded. In another, a Douglas fir tree—the second largest in Canada, in fact—stands alone in a clear-cut forest. “For most, the world is no longer a very nice place to be,” Zelman writes in the book’s preface.

Zelman would be the first to admit he’s an unlikely bard of the nonhuman world. While he’s always enjoyed the outdoors, he’s spent much of his career as a photographer in the advertising and fashion industries. He became interested in humanity’s transformation of the Earth in 2013, after he started wondering why the forest near his home in California had become overgrown. That initial curiosity led him to research federal fire-management policy, but he didn’t stop there. Soon he was learning about invasive species and industrial agriculture, sound pollution, and rising sea levels—and traveling the country to photograph their consequences. “This was a personal exploration that became a total obsession,” he said.

That obsession would shift not only Zelman’s understanding of his local environment but, ultimately, his entire worldview. Everywhere he looked, he saw signs of humanity’s vast ecological footprint. He came to see his commercial work—and the consumer culture it promotes—as part of the problem, and fantasized about becoming a subsistence farmer. As the scope and speed of ecological destruction dawned on him, he experienced a bout of depression for the first time in his life, causing him to briefly put his project on hold. “It gut-punched me,” he said.

A desire to share his discoveries with the world brought Zelman back to photography. But while he’s happy if his images inspire readers to consume less, vote responsibly, and pursue local initiatives that protect wildlife, his book is not intended as a work of advocacy: “The point of this book is to not make people feel bad or guilty about themselves. It’s to say, ‘Here’s a big picture of what we’ve done.’”

When pressed for his assessment of the kind of change required to halt the wholesale decline of biodiversity, Zelman said he subscribes to the “Half-Earth” plan of E.O. Wilson—the acclaimed biologist who contributed a foreword to the book—which proposes that half the planet be permanently set aside as a nature preserve. He’s heartened by the recent surge in environmental activism—and he has himself gotten involved with an initiative to restore mangrove forests. But unlike Wilson, and other environmentally concerned imagemakers, Zelman thinks the time for truly meaningful action has passed. As his book’s matter-of-fact title suggests, he’s resigned to the fact that the next chapter for life on Earth will be even darker than the present one. “The world needs more optimistic people, but I’m not one of them. I feel like we’ve thoroughly wrecked things,” he told me. “I wish I had a solution or something positive to say but I don’t. I’m just sad as hell.”

The American alligator has remained mostly unchanged for 150 million years, managing to survive the mass extinction that killed off the dinosaurs. By the 1970s, it had been hunted almost to extinction for shoes and accessories but was fortunately placed on the federal endangered species list in 1973 and, due to a remarkable comeback, was removed from the list in 1987. Less than half of 1 percent of species listed as endangered have ever been recovered to the point of being removed from the list.

There are over 4,000 native bee species in North America, most of which are solitary and ground-dwelling. Despite the rallying cries of a thousand bumper stickers, the Western honey bee is hardly the species in greatest need: Domesticated for thousands of years, it’s found on every continent but Antarctica and spreads pathogens and agricultural pesticides harming native bee populations while competing with them for resources. The “Save the Bees” movement, focused on honey bees, is really an issue of human agriculture.

Originally from Southeast Asia and introduced through the pet trade, the Burmese python has established a strong breeding population in saw-grass marshes and has devastated mammal and bird populations in the Florida Everglades. In this area, threats to biodiversity and ecosystem balance have caused the loss of 98.9 percent of opossums, 99.3 percent of raccoons, and 90 percent of bobcats. A recent study of the marshes concluded that cottontail rabbits and foxes are locally extinct, while dozens of other species are quickly becoming what is called “functionally extinct.” Their populations are now too small to sustain or maintain a healthy genetic diversity, and local extinction is inevitable. While the National Park Service has removed more than 2,000 Burmese pythons from the Everglades since the early 2000s, it estimates that over 150,000 are actively breeding.

Eighty percent of the terrain of the continental United States is located within a half-mile of a roadway. Combined with the inescapable sounds of commercial aircraft, traffic noise distresses wildlife populations everywhere in America. Sound levels in critical habitats of our national parks routinely measure two to 10 times natural levels, and these are the quiet places. Levels this loud are deadening perception of 50 to 90 percent of sounds and damaging species’ communication, navigation and mating vocalizations, as well as the well-tuned balance between predator and prey.

It’s difficult to photograph a mass extinction, but if I had to reduce these images to a singular concern, it would have to be this one: Agriculture.

Forty percent of Earth’s land surface has been transformed for agriculture, with 30 percent of all existing

terrain purposed solely for livestock, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. In a

2016 study of 3,700 species by the Zoological Society of London and the

World Wildlife Fund, the number of wild animals worldwide was found to have been cut by half in the past 40

years alone. In that same time, amphibians were reduced by 80 percent and freshwater fish by 65 percent.

Thirty-two percent of vertebrate species surveyed in 2017 were decreasing in population size and range, with

over 40 percent of mammals experiencing severe population declines. Rivers and lakes are the hardest-hit

habitats, with animal populations down by 81 percent since 1970 due to water extraction, pollution, and

dams.

The U.S.-Mexico border is home to numerous wide-ranging animals, including bighorn and pronghorn sheep, the Mexican gray wolf, ocelots, and the elusive North American jaguar, along with dozens of others that migrate north to south and back again each year. Also in range are 1,500 other native animals, 62 of which are listed as critically endangered. As the planet’s temperature increases, animals and plants are currently migrating to cooler zones, up slopes and toward the poles.

Building a 1,500-mile-long permanent barrier across one of the most sensitive landscapes in America, in

addition to the impact on humans, could split breeding animal populations in half. It could also leave the

southern creatures trapped while the other half slowly migrate to the cooler north.