Congressman Duncan Hunter seemed in no hurry to get back inside to the Christmas party at a Capitol Hill Mexican restaurant thrown by a Norwegian weapons company, so we each lit up another cigarette, and he called me a bitch for smoking Marlboro Lights. Hunter preferred unfiltereds, but that night, the Republican firebrand wasn’t above bumming one of mine. I took a small bag of medical weed from my pocket, packed some into a bowl, and lit it up. The world is hard for me to deal with on a good day, but a solid sativa makes every day a good day. That day—the first I’d really spent with Hunter—I’d learned he’d read all the books in the Dragonlance Chronicles series and had been smoking since he was a teen. I also learned that if I offered pot to him, a former Marine and member of the House Armed Services Committee, he’d express a connoisseur’s interest in it. I was more innocent then and less jaded, so this genuinely surprised me. The simpatico seemed real: two combat veterans, who long ago short-circuited their self-destruct buttons, ’bout to burn it down.

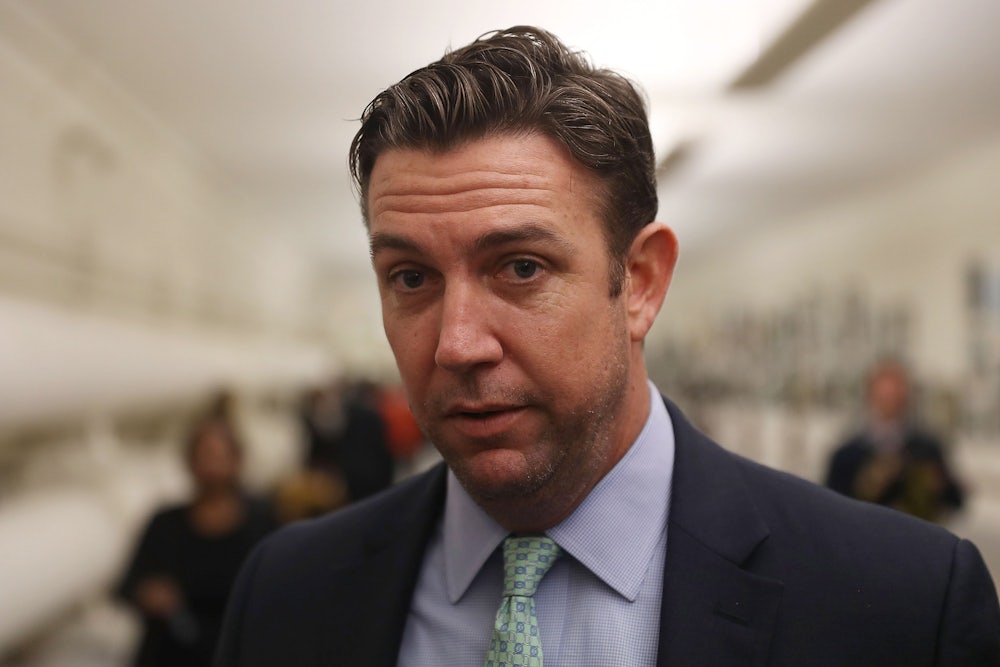

This was four years ago, at the beginning of the now-ubiquitous political strangeness, during the winter rise of Donald Trump from dark-horse to presumptive Republican presidential nominee. Today, Hunter is officially a criminal and a soon-to-be-former congressman, having pleaded guilty this week to stealing campaign funds, a charge he once virulently denied and blamed on his wife. Back in December 2015, Hunter’s political career was at its apex, his name mentioned in the media often and positively, but he was a man in a complicated boxing match with two shadows: his own and that of his father, a Vietnam vet whose congressional seat he’d inherited.

Hunter fils was also a military bro, enjoying the hell out of his status and the perquisites inherent in his office. He was a smarmy, vaping bastard but also one who had no qualms about enraging a four-star general in House hearings, going to bat against the Army over its acquisitions and careerism, demanding a more generous military awards process, and seeking to get free tobacco shipments to overseas troops. He also defended service members against war crimes charges long before Trump adopted the cause: Like the accused, Hunter would later say, he’d taken abominable photographs of corpses while at war, and his artillery unit had “killed probably hundreds of civilians” in Iraq. “Probably killed women and children, if there were any left in the city when we invaded,” he’d said. “So do I get judged, too?” It was a statement of supreme privilege, but it also captured the earnest internal conflict for many veterans sent to do the killing by politicians who faced few consequences for their nifty little wars.

Back at the restaurant entrance, Hunter’s chief of staff intervened just in time to save him from a potential problem—don’t do drugs with the media—and hustled the politician back inside to schmooze a donor. I was left with little to do but finish my bowl and ponder the day.

Hunter was everything one could expect of a fratty, safe-seat Republican legacy congressman, from his military brand to his goofy Southern California affect. But he was also amazingly unguarded—and dismissive of guardrails—in the two days I spent following him that winter. Looking through my notes from the trip, I now realize it marked a major turning point in my personal political education: I had peered inside the belly of the Beltway beast and found I preferred to stay in Arkansas. I’m not sure Hunter’s view of Washington was any more sanguine than mine.

I was working on a book about the sad saga of Sergeant Bowe Bergdahl, and Hunter was one of the few players in that whole ordeal whose involvement didn’t wind up stinking. His congressional office functioned as a safe space for servicemen thrown under the bus by the military. He helped an iconoclastic Army lieutenant colonel and Green Beret named Jason Amerine blow the whistle on the messed-up state of the American hostage-recovery process, a bureaucratic Ouroboros that found a National Security Council representative threatening Kayla Mueller’s parents with the FBI while their daughter was still an Islamic State hostage. In this sense, Hunter was an unofficial Department of Defense ombudsman, trying to keep the brass in the five-sided wind tunnel on their toes.

That year—the year Hunter became famous as the first member of Congress to vape in open session—he successfully cajoled officials in the Obama administration to appoint a State Department special envoy for hostage affairs. That December, the envoy was Julia Nesheiwat.* A year before her appointment, Nesheiwat’s estranged brother-in-law, Creed lead singer Scott Stapp, had been living in a Holiday Inn, claiming in an apparent psychotic break that he’d uncovered the core of ISIS within his own family. (The U.S.’s most recent hostage envoy, Robert O’Brien, earned Trump’s approval by securing A$AP Rocky’s release from a Swedish prison and now runs the National Security Council.) That was the backdrop against which I had gone to Washington to meet with Hunter, with arms wide open.

Not that he wanted to talk for long in his office. Hunter’s Armed Services Committee—which his father had once chaired—was in subcommittee session; he was off the hook for a few hours. Hunter told me to meet him later at the National Republican Capitol Hill Club, where it was always five o’clock and a flesh-pressing congressman could catch up on the political buzz.

Rule V of the Capitol Hill Club states: “Gentlemen will please wear coats and ties in the main dining room. Coats with sport shirts will be acceptable throughout the other areas of the club.” In 2010, the very exclusive 65-year-old club—a “home away from home,” as Georgia congressman and future disgraced ex-Trump Cabinet member Tom Price called it—was sued for discrimination. One of its fixtures was the outgoing speaker of the House, John Boehner, who drank merlot poured from a bottle with his face on the label. The speaker was set to retire at the end of the year, and as I settled in, I noticed a flyer for “John Boehner Appreciation Day” the following month: Attendees could RSVP to either of two receptions: “VIP,” at $500 per person, or “Appreciation,” at $100 per person ($200 for nonmembers). The money went to the “Monumental Scholars Fund,” a Catholic school charity Boehner promoted.

Hunter was joined at our scrum by his chief of staff, Joe Kasper, a hyperactive, talkative, former A-10 mechanic who lived on the constant give and take of congressional politics and would later become an assistant Navy secretary under Trump. They sat downstairs, a few paces from the brass-colored elevators and marble lobby, on tastefully upholstered federalist chairs in a room decorated like an English estate. Others joined the freewheeling discussion. Hunter joked with an ex-helicopter pilot who’d served in the Army’s elite Task Force 160. The pilot, who’d retired as a colonel, looked comfortable in his new suit. He and his wife discussed how much they were enjoying their second act outside the Army: The pilot was now working for NAMMO, a Scandinavian ammunition manufacturer. They secured the congressman’s promise that he’d attend their “winter holiday party” that night at Tortilla Coast, the Mexican restaurant near the Capitol. Later, a retired general and former member of Congress, now working for a defense contractor, lugged in some sort of metal strut in a canvas bag, trying to sell the congressman on its military applications. One of Hunter’s aides, the daughter of a Navy SEAL officer from the home district in San Diego, arrived with the cell phone I’d left in her BMW, gave it to me, and left again.

The Bergdahl case—the case I’d really come to discuss with Hunter—was again in the news. The House Armed Services Committee’s blistering report on the prisoner swap that freed him from Taliban captivity was officially due out the next day, but portions of the nearly 100-page document had leaked out in drips and drops, including the possibility that a ransom was paid. Hunter and Kasper had given me some good oral and written background related to the case, with a little spin mixed in. But when Bergdahl’s name came up at the Capitol Hill Club, the retired general who was hawking military truck parts offhandedly suggested the Army drop him out of a helicopter. The group kept talking shop.

The primaries were still raging, and Frank Luntz, the media-thirsty Republican messaging guru, was quietly warning Republicans in Congress to stop making fun of Trump, who was probably going to be the nominee. Hunter and Kasper took this admonition seriously—so seriously, in fact, that Hunter would become one of the first members of Congress to endorse Trump, well before “DJT” (as Kasper called him) secured the nomination. “He’s just like he is on TV,” Hunter would later tell a crowd of California Republicans of Trump. “He’s an asshole, but he’s our asshole.”

Hunter bought another bottle of champagne, proposed a toast to the passing of the omnibus budget proposal, and then headed off to the Capitol for the final vote of the day. Work wasn’t over; far from it. There was still Tortilla Coast.

The bartender at Tortilla Coast saw these kinds of parties all the time. Special interests rented the place, bought the men and women of Congress dinner and plenty of drinks after a long day of legislation, then made their pitches. But this company made bullets, and to the bartender, it seemed a little … tone-deaf to have a big bullet party on the Hill a week after Syed Farook and his wife, Tashfeen Malik, used rifles and pistols to murder 14 people and injure 22 more at a holiday party in San Bernardino, California, the deadliest terror attack in America since 9/11. “How about doing something about the mass shootings?” he asked me.

Gourmet cupcakes, protected in pink boxes stamped with the NAMMO logo, were on a table close to the entrance, next to spiral-bound catalogs of the company’s wares. A retinue of staffers and hangers-on thrilled for free food and drinks filed back toward the chafing dishes and bar. Trent Lott, the Senate majority leader turned lobbyist, held court at one table. Near the bar, a lobbyist with the National Sheriffs’ Association in a garish suit recounted his testimony on Capitol Hill that day and explained to me why every sheriff in the United States needed a Vietnam-era M113 armored personnel carrier to keep our boys in blue safe. Kasper, beer in hand, kept an eye on Hunter as the boss slipped out for a cigarette. Hunter was trying to quit, always trying to quit, but it was hard. Politics encouraged many bad habits.

I joined him outside—before I quit smoking, I could always use a cigarette—and I asked him random questions. The military is big on reading lists, so I asked what kind of stuff he liked to read, and he did the rare impolitic thing: He told me the sad truth. He really liked the Dragonlance Chronicles, having read them as a teenager. “I have a whole shelf back at home,” he told me.

“Tanis Half-Elven?” I asked, to make sure I was hearing him right. I’d read the Chronicles as an Air Force brat in Germany. Hunter recognized the reference immediately: Tanis was one of the series’ heroes, an orphan torn between two worlds, who has to keep his shit together and lead the Heroes of the Lance on their adventures. Hunter and I had a sudden understanding: We were both very lonely in our youth. This was no conventionally bent, conventionally cold politician; his geekiness and his zeal for mixing it up with the brass made me think of Private John Winger, Bill Murray’s character in Stripes—if Winger had gotten out of the service, been gifted a seat in Congress, and pushed every personal, political, and legal boundary to its limit.

The next summer, at a wedding in the Georgetown Four Seasons, I heard Hunter was in the running for the national security adviser slot that Mike Flynn would eventually, briefly, secure. That idea seemed crazier than Peter Bergen dancing Gangnam-style, which I am sad to report I also saw that night. The wheels began to come off after Trump got elected. When the FBI comes after a politician, they like to get a politician, and Duncan Hunter made it easy for them. He wasn’t a skillful enough criminal to hide his penny-ante personal fraud from the public. He didn’t have his shit together in his personal life. He made powerful enemies in the defense establishment. The result was a 60-count federal indictment that alleged Hunter had used campaign funds to pursue relationships with five women who weren’t his wife. In fairness, he also paid his wife out of campaign funds. He also allegedly tried to coordinate a visit to a U.S. naval base in Italy to give official cover to a family vacation. He also charged the taxpayer to ship a rabbit. He pleaded guilty to only a single charge, but none of the allegations sounded out of character.

In my lifetime, Congress has always been terrible, but it hasn’t really produced a weird-but-damn-likable political criminal since Jim Traficant, the footballing Ohio Democrat who was accused of racketeering as a sheriff and parlayed that notoriety into 10 terms in Congress, then was expelled from the House and sentenced to eight years in prison for misusing campaign funds, like Hunter. Traficant even considered running for Congress after his prison release, but he died in 2014 after flipping a tractor on his Ohio farm.

After Hunter’s plea this week, a friend of mine who knows him well texted me: “Duncan fucked up. He is immature. He did all kinds of stupid things. But that personality trait that undermined his career also made him effective. All he wanted to do was stir the pot and help people, then get drunk after.”

Hunter was corrupt, of course, and conventionally so for a congressman. But no other congressman seemed willing, say, to engage in a testy exchange with General Ray Odierno over how to equip downrange soldiers. It takes a certain kind of reckless confidence to parry a famously intimidating six-foot-five Army chief of staff—and it seemed to me that that was what Hunter was good at. It would be great to have fewer members of Congress who bilk their own campaigns for personal profit. But it would also be great to have just a handful of members whose real passion, like Hunter’s, was making the Pentagon look in the mirror.

* A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Julia Nesheiwat was the first special envoy for hostage affairs at the State Department.